Remote Pauhunri peak lies in the Eastern Himalaya, on the border between Sikkim, India, and Tibet. In 1911, it became the highest peak ever summited, yet it remains little known compared with other Himalayan peaks.

Pauhunri rises above the Teesta Khangtse Glacier to the west and northwest, and the Teesta River valley to the south. Nearby, Chholamo Lake, one of India’s highest at 5,099m, adds to the area’s beauty.

According to most sources, Pauhunri is either 7,128m or 7,125m, but according to Eberhard Jurgalski’s updated measurements, it is 7,107m, with a prominence of 2,014m, making it a major independent peak.

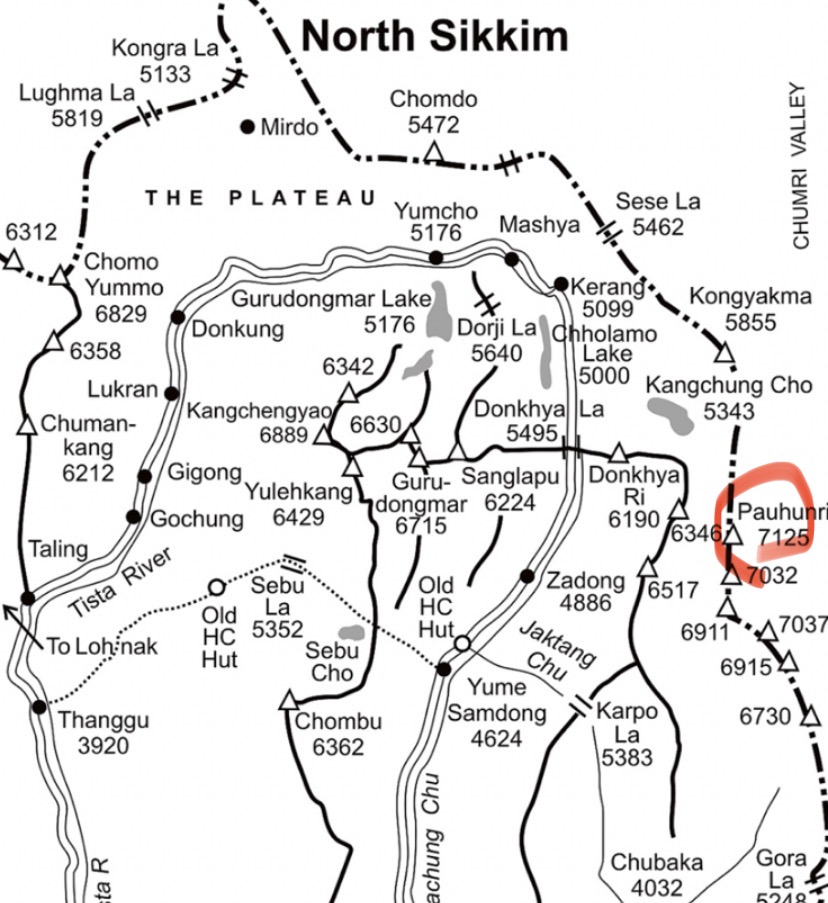

Pauhunri marked in red. Photo: American Alpine Journal

Long approach, few ascents

Climbing Pauhunri is not extremely technical — its routes are graded PD+ to AD on the Alpine scale, with snow and ice slopes. However, its high altitude, harsh weather, and long approach make it tough. Reaching the peak requires a multi-day trek from Lachen in North Sikkim, the closest town with a road, through glaciers and rough terrain.

Pauhunri’s difficult access has kept it off most climbers’ lists. It has been climbed only five times, by around 10 people.

The first ascent

Alexander Mitchell Kellas was born in 1868 in Aberdeen, Scotland. He was a chemist, teacher, and mountaineer whose work changed Himalayan climbing.

Kellas’s love for mountains started in the Scottish Highlands and then the Alps, but he eventually focused on the Himalaya. Between 1907 and 1921, he made eight trips to Sikkim.

In 1910, Kellas scouted the Kangchenjunga region, including Kirat Chuli, as part of his broader exploration of the Sikkim Himalaya. Kellas’ goal was to study the geography, assess potential climbing routes, and gather data on the effects of altitude. That year, he climbed 6,965m Langpo, which has only two ascents, both by Kellas.

A.M. Kellas (1862-1921). Photo: Alpine Journal

Kellas and his two Sherpas, Sony and “Tuny’s brother,” carried out the first ascent of Pauhunri between June 13 and 17, 1911. It was Kellas’ fourth Sikkim expedition.

From Sikkim, to Tibet, to the summit

The trio took a route from the northwest, starting in North Sikkim and approaching via the upper Lhonak Glacier. This glacier lies on the Tibetan side of the border but was accessed from Sikkim. Their long approach went via the Lachen Valley to the village of Lachen, then to the Lhonak Lake area and up the Lhonak Glacier, which descends northwest from Pauhunri toward the Tibetan plateau.

From the glacier, they ascended a steep, loose section on mixed terrain to a prominent col on the northwest side. From there, they followed the northeast ridge to the summit, topping out on June 14 without supplemental oxygen.

This climb, done without fixed ropes, was advanced for its time. At 7,128m, the team set a world altitude record, beating Tom Longstaff’s 1907 climb of 7,120m Trisul. The record fell again in 1930, with the first ascent of 7,462m Jongsang Ri.

Early maps misjudged Pauhunri’s height, so the record was not fully recognized until the 1980s. Some sources, like the American Alpine Journal (2008) and author Jill Neate, list 1910 for this climb, but Kellas’ own notes published in the Alpine Journal in 1912, confirm the 1911 date.

The source of the Teesta River: Cholamo (also spelled Tso Lhamo) Lake in North Sikkim. Photo: Mamta Chhetri

Kellas’s legacy

Kellas valued the help of Sherpa and Lepcha porters, unlike many climbers of his time. Sadly, the names of his porters in 1911 were not recorded, a sign of the era’s focus on Western climbers.

Kellas also climbed 6,835m Chomiomo in 1911 and made maps and photos that helped later expeditions to Kangchenjunga and Everest. Kellas died in 1921, aged 52, from dysentery during the first British Everest expedition. He died before reaching the mountain. Forgotten for decades, his story was revived in the 2011 book Prelude to Everest by Ian R. Mitchell and George W. Rodway.

Kellas’s Pauhunri climb was his greatest achievement, and a major event in mountaineering history, although underrated at the time. With two Sherpa porters, he summited using a simple, lightweight style, climbing the northwest ridge without fixed ropes. This was unusual at a time when most expeditions were large and complex.

During the climb, Kellas studied how altitude affects the body, measuring pulse and breathing, and testing oxygen equipment. His 1917 paper, A Consideration of the Possibility of Ascending the Loftier Himalaya (Geographical Journal), said Everest could be climbed without extra oxygen if climbers adapted to altitude — a bold idea proven true in 1978. He also pushed for using oxygen tanks, which later helped Everest climbers in the 1920s.

Pauhunri from Chholamu. Photo: The Himalayas Are Calling

Four more ascents

In 1930, a large Swiss-led team under Gunter Oskar Dyrenfurth set out to explore the Kangchenjunga region in Sikkim. This international group, including Dyrenfurth’s wife Hettie, climber Fritz Wiessner, and local Sherpas, wasn’t solely focused on Pauhunri but aimed to scout the Zemu Glacier’s peaks. They trekked through Sikkim’s rugged terrain, setting up camps amid snow and mist.

On a clear June day, a small party from the expedition tackled Pauhunri’s north ridge, the same route Kellas had pioneered. They reached the summit, marking the second confirmed ascent. It wasn’t their main goal — Kangchenjunga loomed larger — but Pauhunri’s summit was a proud side achievement.

After World War II, the Himalaya beckoned adventurers again, and a third ascent took place, although there are no details. By the 1980s, India’s mountaineers were taking charge in their Himalayan backyard, especially in restricted border zones like Sikkim.

Around 1986-1988 (records disagree on the exact year), an Indian Army team set its sights on Pauhunri. Details are scarce because military climbs often stay under the radar, but they followed the same north col route from the Chholamo Glacier. Facing brutal winds and snow, they pushed to the summit, marking the fourth ascent.

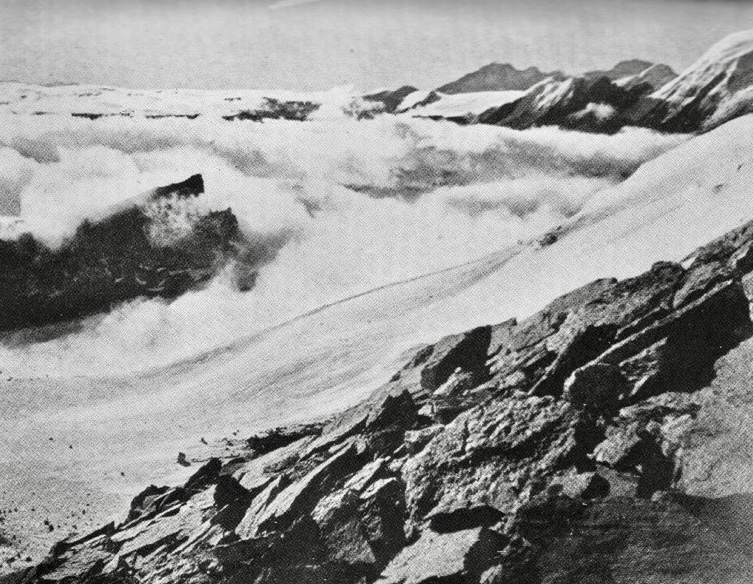

View towards Pauhunri from Camp 1 on Chomiomo. Photo: G. Crosby/Himalayan Club

The last registered ascent

In November 1989, three climbers from Sikkim’s Sonam Gyatso Mountaineering Institute (Nawang Kalden, Nima Wangchu, and Pasang Lhakpa) decided to climb Pauhunri as a training mission. Starting from a base camp at 5,100m on the Chholamo Glacier, they set up two higher camps, battling cold and altitude. On November 1, after a grueling 7.5-hour push from their Camp 2 at 6,210m, they stood on the summit.

Pauhunri’s five ascents over 78 years make it one of the least climbed 7,000m peaks, with no evidence of post-1989 ascents.

Only the northern routes are known, with no attempts recorded on other sides. Pauhunri stays forgotten because it lacks the draw of bigger peaks, and is hard to reach because of its isolation and border sensitivities. Yet, for climbers seeking rare challenges, it offers a unique adventure.

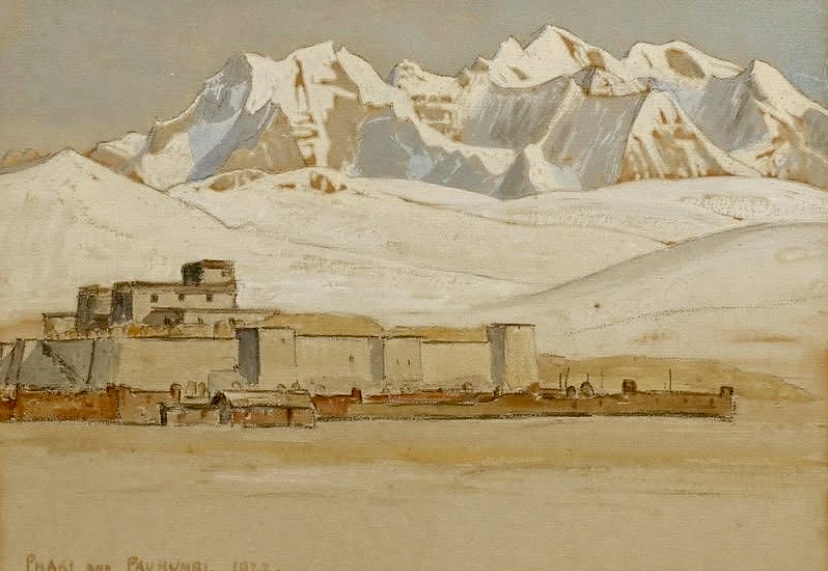

Phari and Pauhunri, 1922. A watercolor by one of the 1922 Everest expedition members. Photo: Duke Auctions via Bob A. Schelfhout Aubertijn