When you think of Herman Melville, you probably think of his Great American Novel, Moby Dick, being assigned reading in high school English class. But during his life, people mostly knew Melville as “The Man Who Lived With Cannibals.”

Before he was a writer, Melville was a sailor, whaling man, and all-around maritime adventurer. Melville’s writing often drew from his personal experiences at sea in his youth, none more so than his very first novel. Typee, published in 1846, is an autobiographical account of his time in the Marquesas Islands.

It was his most popular book during his lifetime, and it haunted him for the rest of his career.

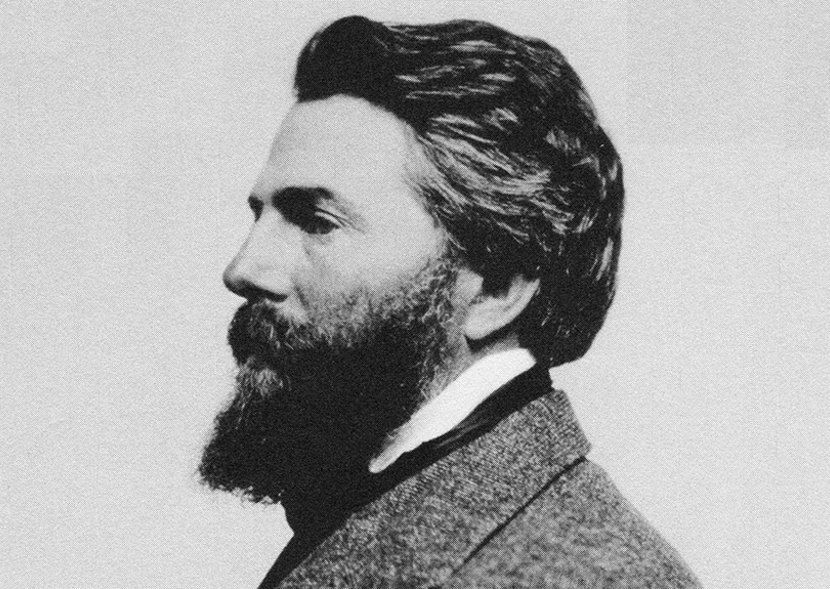

Melville around 1860, nearly two decades after leaving the Marquesas. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Melville, the explorer

Most people are, as I’ve said, at least passingly familiar with Melville the writer. Melville the explorer, however, is less well remembered. But his biography is as complex and mysterious as his novels.

The scion of two prominent East Coast families with American Revolutionary pedigrees, the Herman Melville born in New York City in 1819 had a life of luxury to look forward to. When Melville was 11, however, his father told his family the truth: His prosperous business was a front for failure and debt. They fled to Albany, leaving bills unpaid, and when their father died two years later, Melville and his brother Gansevoort had to leave school to work.

After several failed ventures, Herman went to sea for the first time in 1839. He worked as a novice sailor on a merchant ship transporting cotton to Liverpool. In 1841, he signed up for a whaling voyage on the Acushnet.

Despite his poetic flights about the noble whaling life in Moby Dick, it didn’t seem to suit him very well. After 15 months — perhaps a third of the expected voyage — he’d had enough. The ship had stopped to pick up supplies in the Marquesas Islands, and Melville bolted into the jungle along with a friend. The plan was to explore and live off the land.

Instead, Melville was basically immediately captured and spent a month living with the Tai Pī people of Nuku Hiva. Three years later, he published the book Typee.

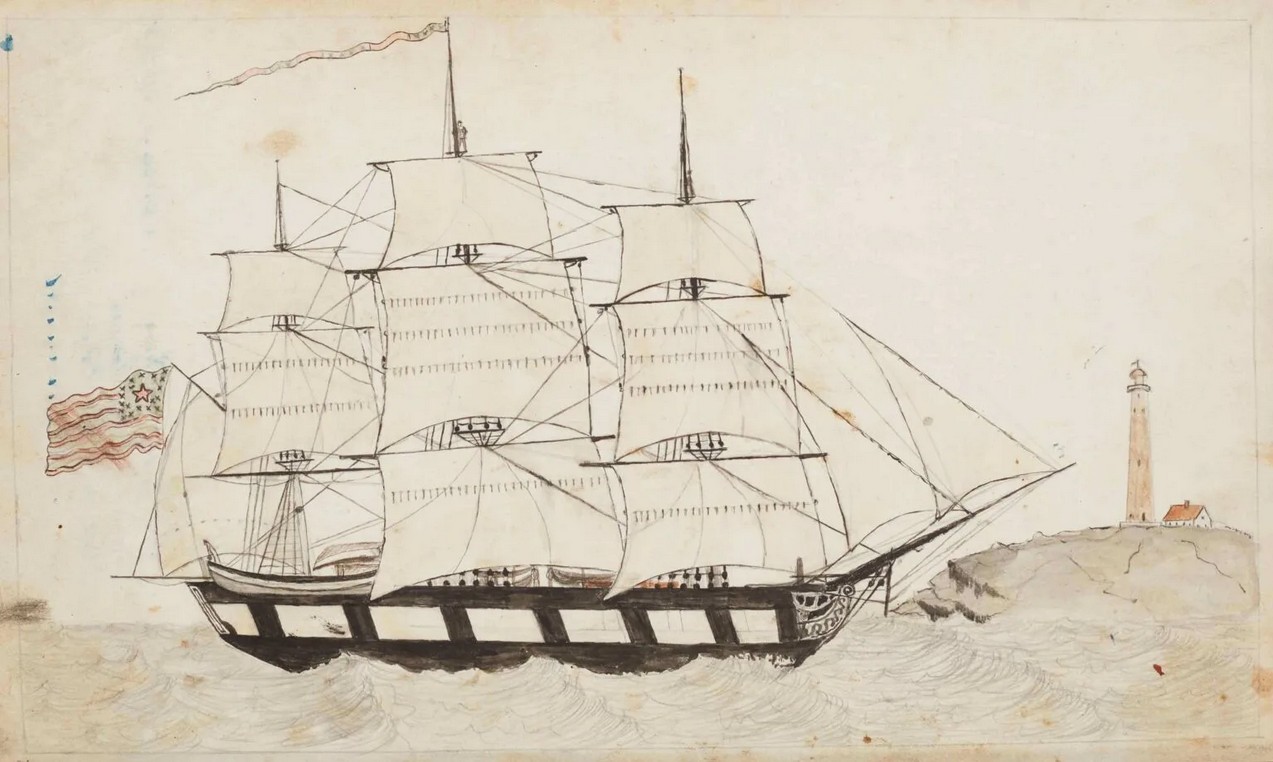

An American whaling ship at sea in the 19th century. Life aboard was hard, and the voyages lasted several years. Photo: Public Domain, The Whaleship ‘Emma C. Jones’ off Round Hills, New Bedford by William Bradford

Typee, A Romance of the South Sea

The Marquesas! What strange visions of outlandish things does the very name spirit up! Naked houris—cannibal banquets—groves of coconut—coral reefs—tattooed chiefs—and bamboo temples…

Herman Melville, Typee

Typee opens with Tommo, the semi-fictional stand-in for Melville, on a whaling ship in the bay of Taiohae, on the South Seas island of Nuku Hiva. Sick of the bad food and their ill-treatment at the hands of the ship’s captain, Tommo and a fellow whaler, Toby, decide to make a break for it. Ignoring the captain’s warnings that the island is dense with cannibals, they slip away from a shore party and into the mountains.

Almost immediately, their adventure goes belly-up. Tommo injures his leg, they’re hindered by dense vegetation, and they run out of food. According to their limited knowledge of the area, they are on the border between two groups. The Happar are friendly and might help, while their enemies, the Typee, are vicious cannibals.

After days of struggle in the jungle, they meet a group of islanders who, of course, turn out to be the Typee.

The bay of Taiohae today, which Melville calls the bay of Nuku Hiva. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Reputation and reality

The pair is fed and sheltered in the home of a leader, Mehevi. Suspicious of the Typee, Toby soon escapes, while the injured and more complacent Tommo remains. There, he befriends several of the Typee. Eventually, however, they push him to fully integrate into the group, and he flees back to the bay, hopping aboard a passing European vessel.

The bulk of the novel covers Tommo’s time with the Typee, and the adventure takes a backseat to something more like anthropology. Melville describes the food, houses, religious traditions, and social organization of the valley, which has had very limited contact with Westerners.

But his time in the valley, and the book itself, is haunted by an act which never actually takes place, at least not explicitly: cannibalism. Both Tommo and the readers are constantly led to question the truth of the Typee’s reputation for anthropophagy, and what it means if they do practice cannibalism.

Before Toby escapes, he and Tommo attend a feast. When they are served meat, Toby refuses to eat, insisting it’s a “baked baby,” or “dead Happar.” Tommo, not so sure, takes a closer look and confirms that the dish is only a pig.

However, weeks after, Tommo finds four preserved heads, including one that seems to be from a white man, belonging to Mehevi. Later, Tommo is barred from attending a celebration feast and religious ceremony involving the bodies of recently slain enemies.

‘Why, they are cannibals!’ said Toby on one occasion when I eulogized the tribe. ‘Granted,’ I replied, ‘but a more humane, gentlemanly and amiable set of epicures do not probably exist in the Pacific.’

Herman Melville, Typee

Tommo believed Mehevi was ‘the sovereign of the valley,’ who had taken him under his protection. He described Mehevi as a courteous and generous ruler, who, ‘from the excellence of his physical proportions, might certainly have been regarded as one of nature’s noblemen.’ Illustration by Mead Schaffer for the 1923 edition

Fame and controversy

The book never fully resolved the cannibal question. While Tommo never witnesses it, he leaves still convinced that the Typee do, on some occasions, practice it, though only against defeated enemies.

But by the end of the narrative, Melville approaches the subject with an impressive degree of cultural relativism. After all, he argues, what is “the mere eating of human flesh,” compared with European practices like drawing and quartering?

Typee became an immediate success, but it was also an immediate controversy. One of the main reasons for this was Melville’s harsh criticism of Western treatment of South Pacific natives, and his criticism of missionaries in particular.

The same month Melville arrived, the French Navy claimed possession of Nuka Hiva. Melville criticized the French for their use of violent force, proceeding to castigate colonial efforts in the region in general.

“The enormities perpetrated in the South Seas upon some of the inoffensive islanders will nigh pass belief,” he opined.

As for the civilizing influences of Christianity and Western civilization, “Let the once smiling and populous Hawaiian islands, with their now diseased, starving, and dying natives, answer the question.”

Passages like these provoked a flurry of negative reviews from conservative Christian publications. Writing for the New York Evangelical, William Oland Bourne called Melville a traducer (slanderer) of missionaries and an “apostle of cannibalism.” Another reviewer said the book abounded in “slurs and flings against missionaries and civilization.”

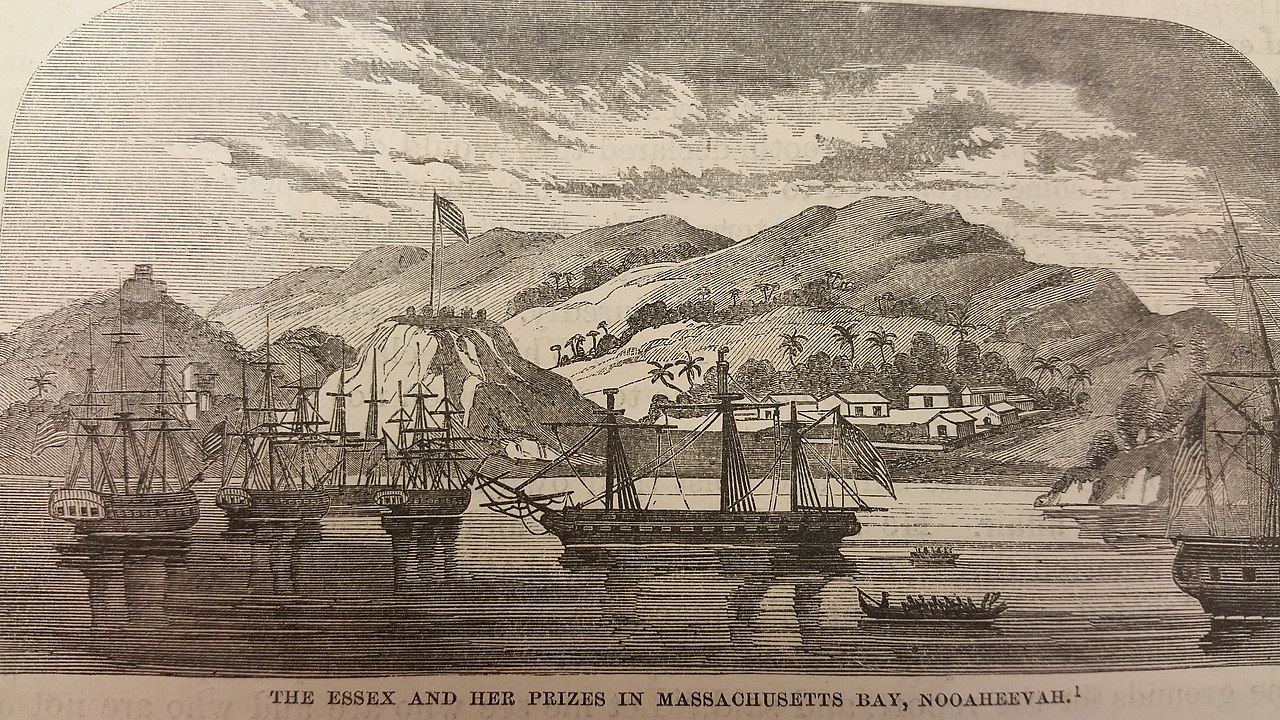

In 1813, U.S. Navy Captain David Porter burned down the villages of the Typee Valley. Melville was highly critical of Porter’s actions, saying that if the Typee were aggressive to outsiders, it was in response to Porter’s own actions. Photo: Public Domain

Melville the fabulist?

Bourne dedicated much of his scathing review to the morality of Typee. But he ended off with an attack on the honesty of Melville’s account: “We are inclined to doubt seriously whether our author ever saw the Marquesas; or if he did, whether he ever resided among the Typees.”

While many reviewers accepted Typee as a mostly accurate autobiography and ethnography, with perhaps a few names and details changed for publication, a vocal minority were in Bourne’s camp. Much of the contemporary criticism stemmed from his sympathetic portrayal of Polynesian islanders. An anonymous reviewer wrote that “those who are at all familiar with the character of the South Sea islanders” would know that Melville’s descriptions of happy, kind people were false.

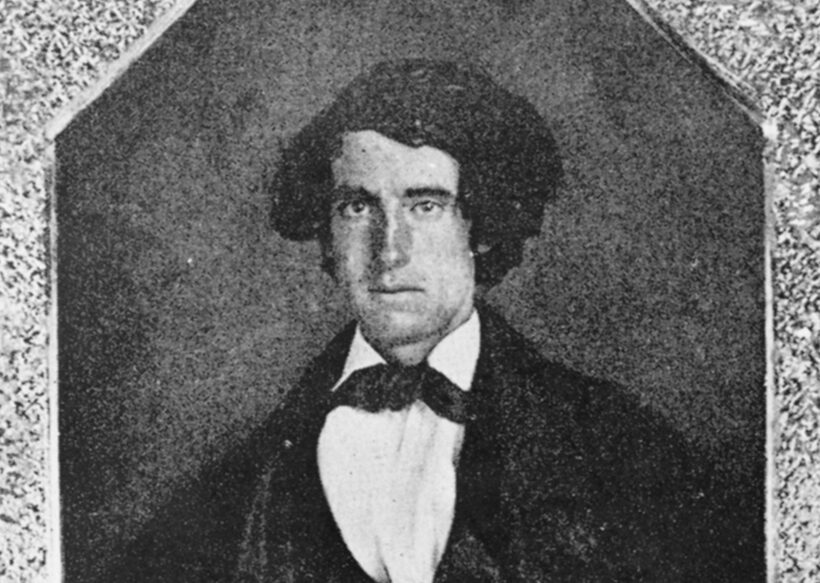

Galled by the disbelief, Melville defended his own veracity. But to the surprise of all, another figure emerged to champion him: Toby. In July of 1846, Richard Tobias Greene revealed himself to be Melville’s erstwhile companion, who had escaped several weeks before him. In a published letter, he offered to testify to the complete honesty of Typee, or at least the parts he was there for.

Richard Tobias ‘Toby’ Greene in 1846. Photo: University of Chicago Library, Special Collections

The varnished truth

In the forward to Typee, Melville claimed to have written “the unvarnished truth.” From what modern investigations have found, he seems to have told a somewhat varnished truth.

Melville scholars in the 20th century revived the debate over Typee, searching for evidence of veracity or fraud. Besides the collaboration from Toby, researchers have found a legal record from the Acushnet‘s captain. Since desertion was a prosecutable offense, the captain produced a signed record of desertions during his voyage. There, in plain ink, is “Richard T Greene and Herman Melville deserted at Nuku Hiva July 9th 1842.”

The most in-depth detective work came from Anderson Roberts with 1934’s Melville in the South Seas. Citing the findings of a 1920 scientific expedition to Polynesia, Roberts concludes that Typee is surprisingly accurate to the environment, customs, and material culture of the Marquesas. But Roberts also discovered that Melville had used earlier published accounts extensively.

There are a number of details in Typee that we know are false. Tommo rows a canoe on a lake that doesn’t match any location on Nuku Hiva. While Tommo was on the island for months, Melville was only missing for 26 days. The whaling vessel is the Dolly in the book, and the Acushnet in reality.

The general arc of the story — that Melville deserted at Nuku Hiva and spent at least a few weeks living there — is fact. But what exactly happened to him there, and how well Typee reflects his experience, will probably always be a mystery.

The whaleship Acushnet was the real name of the Dolly in ‘Typee’, and a model for the famous Pequod of ‘Moby Dick.’ Photo: Peabody Essex Museum

Legacy is a funny thing

It is only a very lucky few writers who manage to be remembered for their work. Of those who are, they don’t get to decide what work they’re known for. Arthur Conan Doyle was sick to death of Sherlock Holmes, and hoped to be remembered his now-forgotten historical novels.

For many decades, it seemed Melville would be similar; remembered for the controversy around his first novel, while his profoundest literary efforts were forgotten. As the man himself wrote to his friend (it’s more complicated than that, but if I get into it we’ll be here all day) Nathaniel Hawthorne that “[The] “reputation” H.M. has is horrible…To go down to posterity is bad enough, anyway; but to go down as a ‘man who lived among the cannibals’!”

Moby Dick was a failure on release. Commercially, it was catastrophic enough to nearly bankrupt the publisher. Critically, reviews were mixed. The London Literary Gazette said Melville should go back to writing autobiographical adventure travel, instead of wasting his time on works like Moby Dick. A New York magazine said Melville “might have been famous,” if he’d stopped at just one or two books.

By the early 20th century, Melville was neglected and long out of print. But in the late 1910s, Melville underwent a revival. Literary scholar Raymond Weaver released the first biography of Herman Melville in 1921, then published Melville’s previously unpublished final novel, Billy Budd.

The “Man Who Lived with Cannibals” was forgotten. But over the first half of the 20th century, the author of the Great American Novel was born.