A new study conducted over 44 years in Alaska has revealed that avalanches can cause major declines in mountain goat populations — declines which can take the goats a generation to recover from.

“Avalanches transform mountain landscapes in major ways that can be both beneficial and deleterious,” said wildlife ecologist and lead author Dr. Kevin White of the University of Alaska Southeast.

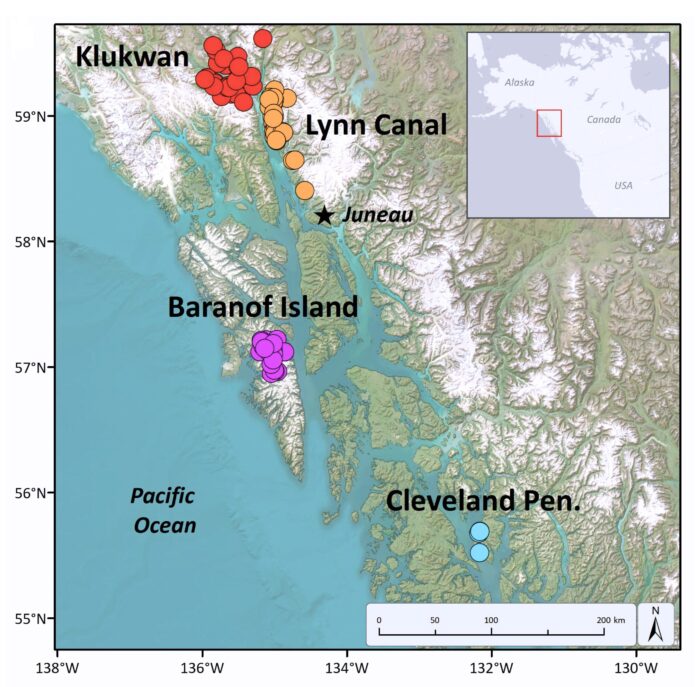

White and colleagues used long-term monitoring data from 600 tagged mountain goats across 14 sites in Alaska from 1977 to 2021.

They also studied in detail a subset of 421 of the goats at four sites between 2005–2021. These goats were fitted with VHF/GPS collars and monitored monthly to determine their survival rates and the cause of death.

Avalanche deaths were confirmed when carcasses were found buried in avalanche debris or within the path of an avalanche.

Map depicting the four study areas and locations where radio-tagged mountain goats were studied and died in avalanches during 2005–2021 in coastal Alaska. Map: White et al. 2025

The researchers took the long-term data from 1977-2021, which gave a picture on survival and reproduction, and combined it with the shorter-term data (2005-2021) on avalanche deaths. This let them model how avalanches affect goat populations in this part of Alaska.

Why are goats hit by avalanches?

Mountain goats are part of a broader group of alpine hoofed mammals found in 70 countries and are very well-adapted to life in the high mountains. However, their survival depends on avoiding predators such as wolves and bears. So they spend much of their time on steep, craggy slopes where predators struggle to reach them.

Mountain goats shelter beneath the fracture line of an avalanche. Photo: Kevin White

But these seemingly safe cliffs come with their own dangers. Even sure-footed goats can slip — it happens — and these cliffs may be prone to avalanches. Managing this balance between safety and risk is challenging, as avalanche hazards are often invisible and triggered by weak layers buried deep within the snowpack.

How much do avalanches impact goat populations?

In a previously published analysis, White and colleagues reported that during an average year, around 7% of mountain goats in Alaska die in avalanches. In more severe years, this can rise to 22%.

Long-term population models in this study estimate that the goat population can grow 1.5% during an average avalanche year, and 7% in years with no avalanche deaths. By contrast, during a severe year, a population can decline by as much as 15%.

Mountain goats lie in dug-out snow pits on an avalanche slope after a storm. Photo: Kevin White

The researchers estimated that after one of these severe avalanche years, it can take 11 years or 1.5 mountain goat generations for the population to return to normal. That’s assuming that another severe avalanche year doesn’t occur in the meantime.

“The naturally slow growth rates of mountain wildlife mean…a ‘bad’ avalanche year can set a population back by a generation or more, while a ‘good’ year only offers a relatively small, incremental boost,” said White.

What does the long-term look like?

The researchers suggest that the changes in population from avalanches recur with every generation and aren’t rare, one-off events. They speculate that climate change may lead to greater avalanche risk in the future for these iconic mountain animals.

Avalanches can also impact their predators, including bears, wolves, and eagles.

Five adult female mountain goats traverse below steep, snow-loaded slopes in midwinter, Takshanuk Ridge, Haines, Alaska. Photo: Kevin White

White and his colleagues don’t offer any practical suggestions, but it seems obvious that management of land use and hunting in mountain goat regions such as Alaska should consider avalanches in their calculations to maintain long-term populations. This might include adjusting or pausing hunting after high-mortality winters to give herds time to rebound.