At age 39, Spanish software developer Javier Carrasco decided to trade the predictability of office life for the uncertainty of the open road.

“You could call it a midlife crisis, or simply the urge to make the most of life before it’s too late,” he said.

Carrasco had lived in Austria for a decade, drawn by the Alps. A lifelong mountain biker who later embraced road cycling, he had made short trips before, “up to a week around Spain,” but nothing major.

Together with his partner, Rebecca (who prefers to keep a low profile), he set off from Italy earlier this year on what is meant to be a year-long cycling odyssey to Central Asia. Eight months later, they have covered 12,000km and climbed over 100,000m.

Carrasco and partner in Mongolia. Photo: Javier Carrasco

Balancing work and the road

Before setting out, the pair found a practical way to fund their travels without cutting ties to home. They arranged with their employers to work half-time for two years, but did all their work in the first year. That way, they kept their insurance and a steady, though reduced, income.

They also saved steadily during that initial year on a half-salary. Carrasco maintains a small online presence as Hacker Bikepacker, which, as he puts it, “doesn’t come close to covering the trip’s expenses but does help extend the adventure a bit.”

Carrasco’s GPS tracks so far. Some data is yet to be updated. Map: Javier Carrasco

He chose not to take on remote work during the trip, “so I could really enjoy the journey without thinking about anything else.”

Initially, the couple planned to spend six months climbing in the Andes. But “it felt a bit repetitive,” Carrasco explained, “and in the end, the idea that really caught us was cycling to Central Asia to see the Pamir Mountains.”

That single idea expanded into a transcontinental route that carried them across Europe and deep into Asia.

Carrasco in Tibet. Photo: Javier Carrasco

Theirs is not a continuous route: They took a train to Korea, flew over prickly Turkmenistan, and caught the ferry from Greece to Turkey, among other shortcuts. On the other hand, they have cycled through some politically sensitive countries, including Iraq, Iran, and Tajikistan. Some of the most interesting terrain has been the high roads that run across Tibet.

Toward the high plateau

Carrasco and his partner entered China at the end of August and spent several weeks exploring other regions before beginning the long climb from Dali, a historic city in Yunnan province in the country’s southwest. From there, their route led north toward the Tibetan Plateau.

“We were there from the beginning of September until one week ago,” Carrasco said.

The gradual ascent through Yunnan’s rugged mountains allowed them to acclimatize naturally.

Carrasco with an admirer in Xinjiang Province, China. Photo: Javier Carrasco

Their first culturally Tibetan city was Shangri-La, located in the northern reaches of Yunnan near the border with Sichuan province. Once known as Zhongdian, the city was renamed after the fictional place in the novel Lost Horizon to promote tourism.

From there, the road wound into the remote highlands of western Sichuan, where Tibetan culture predominates and the air grows thinner.

Songzanlin Monastery, Shangri-La. Photo: Shutterstock

The ride to Litang, a windswept town at 4,000m, took them over passes exceeding 4,700m and into a landscape of grasslands, yak herds, and snowy peaks. “Even seeing monkeys at 4,000m, which we definitely didn’t expect!” Carrasco said.

Tibet

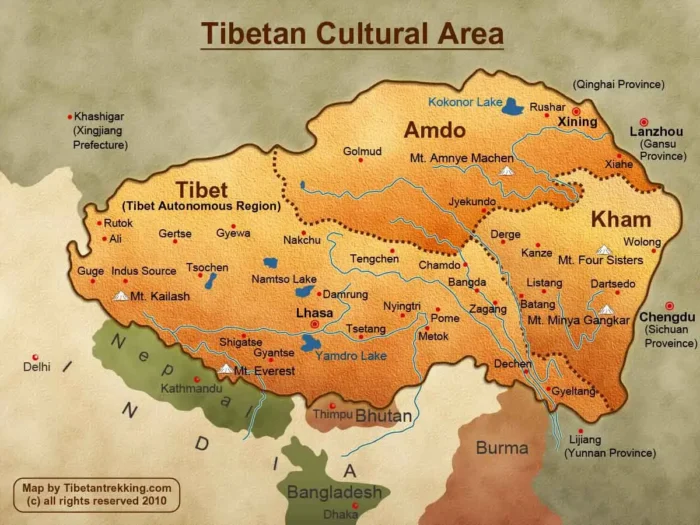

“Most people think Tibet and the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) are the same, but that’s not true,” explains Carrasco.

The Tibetan Plateau stretches across much of Central Asia, covering parts of China, India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan. Within China, it also includes large areas of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces.

Map: Tibetantrekking.com

Culturally, this vast high-altitude region is known as Tibet and is traditionally divided into three regions: U-Tsang, Kham, and Amdo. The TAR corresponds mostly to U-Tsang and is only accessible to foreigners on organized tours, which makes independent cycling there impossible.

The other two regions, Kham and Amdo, were absorbed into neighboring Chinese provinces after Tibet’s annexation but remain largely open to foreign travel.

Despite modern administrative borders, all three regions mostly share a common language, religion, and cultural identity shaped by life on the Tibetan Plateau.

High Roads and hidden monasteries

From Litang, the pair continued north through the remote towns of Ganze and Manigango in western Sichuan, an area of sweeping grasslands and isolated monasteries where Tibetan culture remains deeply rooted.

They then crossed into Qinghai province, reaching Yushu, a major town on the upper Yangtze River. Along the way, they cycled the Chola Pass, “officially 5,050m, though probably around 4,900 according to my GPS,” Carrasco said.

Their highest point overall came earlier in the year on Mount Damavand in Iran, the tallest volcano in Asia at 5,610m, which they climbed before riding into Tajikistan.

Thanks to gradual acclimatization and steady hydration, they avoided any problems with altitude as they moved across the Tibetan Plateau.

Chola Pass. Photo: Javier Carrasco

One stop on the plateau left a lasting impression: Yarchen Gar, a sprawling monastic community officially off-limits to foreigners.

“We visited without knowing it’s off-limits,” Carrasco recalled. “Luckily, we weren’t discovered until the next day, after we’d already seen everything and taken plenty of photos, which I somehow managed to keep.”

Cold roads and kind strangers

The final stretch across Qinghai province, from Yushu to Golmud, proved to a highlight. This section crosses the heart of the northern Tibetan Plateau, a barren region of high-altitude plains and frozen valleys that marks the transition from Tibetan cultural lands to China’s interior deserts.

“A 200km section of remote gravel roads averaging 4,500–4,600m in altitude, with temperatures down to –10°C and a wind chill of –16°C, even though it wasn’t winter yet,” Carrasco said.

He rode that stretch solo, encountering herds of wild donkeys and Tibetan gazelles, and spotting foxes, wolves, and once, a Tibetan bear in the distance.

Tibetan Plateau scenery. Taken on the way from Lhasa to Golmud. Photo: Shutterstock

As the couple descended toward Golmud, a remote industrial city, the wind returned with full force.

“Near the end of the plateau, we had two days of wind so strong and cold that we simply couldn’t keep riding,” he said.

When a sandstorm hit, locals came to the rescue. “Some locals picked us up in their truck, took us to a half-built hospital where one of them worked as a doctor, and gave us a room for the night, inviting us to eat with them. People were always incredibly kind to us.”

On rough roads in Tibet. Photo: Javier Carrasco

Still pedaling

Eight months later, the journey continues. Carrasco and Rebecca are now in Korea, having taken a train to the east coast of China.

“The plan is to travel for a full year,” Carrasco said. “Though who knows what will happen when the ‘return date’ gets closer.”