Opening a new route is every climber’s dream, but finding something new is getting harder all the time. The most obvious lines, whether in the Himalaya or the Alps, have already been done.

The common-sense definition of a new route is a line to a summit or the top of a wall that runs over previously unclimbed terrain. But in mountaineering, the criteria are often not as strict, especially on popular peaks or faces. Some lines share sections with older routes but are still considered “new.” Others become “partial new routes” or “variation routes.” So, what are the differences, and how can we tell one from the other?

The short answer is that there is no clear answer. No official institution has applied jurisprudence to the matter. The UIAA (Union internationale des associations d’alpinisme), for example, has remained silent. In their Declaration on Hiking, Climbing, and Mountaineering, they simply state that the style of a climb should be reported honestly and in detail.

“Criteria change from chronicler to chronicler,” geographer and mountain topography expert Rodolphe Popier told ExplorersWeb.

New, although not 100% new

New routes are easy to classify as such when they cover 100% new terrain. However, routes that cover a significant and substantial amount of unclimbed terrain, creating a new, distinct, and logical line, are usually considered new routes as well, even if they share part of a previous line.

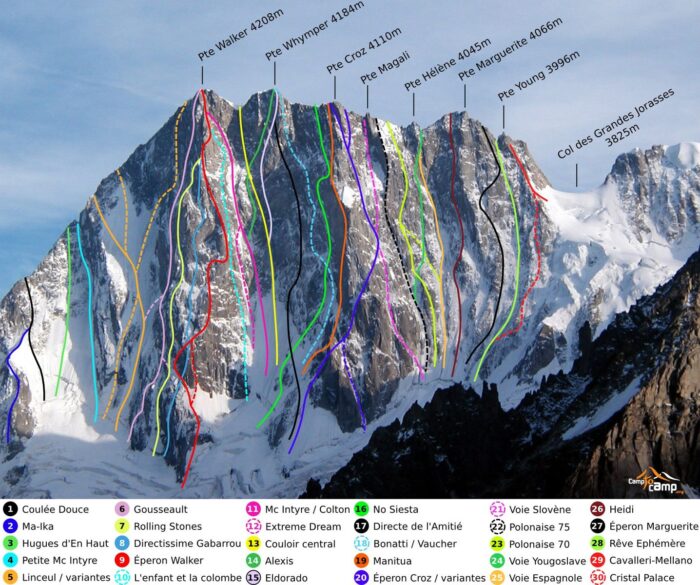

This is very common in classic routes in the Alps. Here, it’s often decisive whether or not a potential new route includes the crux of the climb. Meanwhile, the shared sections are driven by logic; for example, the starting sections or the final pitches to a summit or the top of the wall may overlap with previous routes. A good example is the North Face of the Grandes Jorasses:

Routes up the North Face of the Grandes Jorasses, Mont Blanc Massif. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

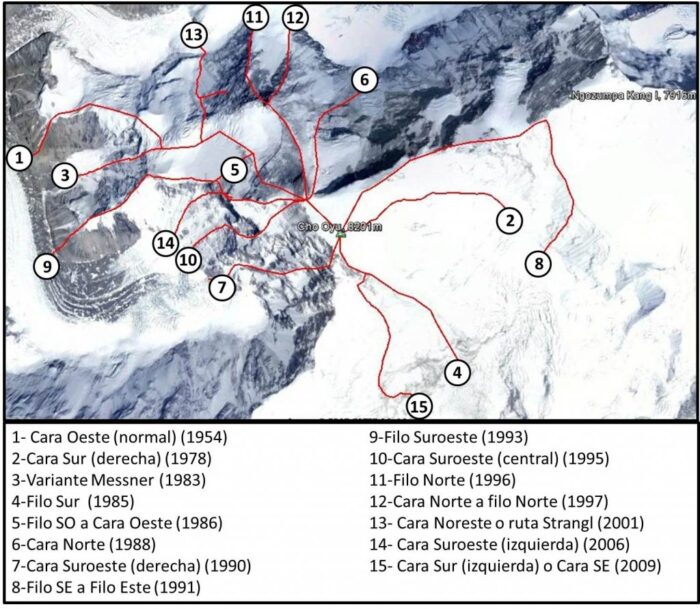

In larger mountains, it is common to have several obviously distinct routes that, nevertheless, share the final section to the summit. For example, they might merge onto the summit ridge or open onto the final plateau.

All Cho Oyu routes, compiled by the Animal de Ruta blog. The four climbs done from the Nepal side are numbers 15 by Urubko, 4 by the winter Polish team, 2 by the 1978 Austrians, and 8 the Russian line along the East Ridge. Note that all the routes from the North and Northwest sides merge onto the summit plateau, but are clearly separate on the rest of the climb and especially the difficult sections.

Partials and variations

If a route shares part of the way with previous routes, and the length and/or significance of the new terrain is not enough, the route is usually considered a partial new route or a variation route. While both terms are virtually the same, a partial new route tends to have more new terrain than a variation.

The difference often lies at the start or the exit of the route: Partial new routes may include, for instance, direct lines up a mountain face, while classic routes often follow longer but also easier lines on milder flanks and ridges.

Routes on the North Side of Everest, compiled by Animal de Ruta on Google Earth. Red indicates the normal North Side route, following the Northeast Ridge. Grey is the direct White Limbo route opened by an Australian team in 1984, and pink/purple is the variation route opened by Reinhold Messner in 1980.

Everest routes on the Kangshung Face, compiled by Animal de Ruta. The yellow line is the Neverest spur, the black line is the American spur, and in red is a never-climbed variation: the Fantasy ridge. On the right, in purple, is the normal route up the North Side, which follows a longer but safer line from the North Col along the Northeast Ridge.

A variation route usually follows a previous line, but at a certain point, it deviates to climb a different feature (a wall, a couloir) and then rejoins the original route. Variations can be done to climb new features or to avoid objective dangers on the route, a logical measure in glaciated mountains, where conditions change from season to season.

A typical case is the classic route on the North Side of Annapurna, where the state of the glacier prompts climbers to take one of several variations each year.

Variation routes to Camp 3 on Annapurna. Photo: Mingma G’s FB

The dilemma

The big question is: When does a route that is partly on new terrain and partly sharing sections with previous routes stop being a new route and start being a variation? And who decides?

We have asked several people, from guidebook writers to chroniclers and, of course, climbers. To our surprise, many in the worldwide climbing community hesitate to share their opinions or even hazard an educated guess.

The silence increases when we ask about specific cases from recent times. In that case, discrepancies are typically resolved by those directly affected: the climbers who first opened the route that another team may claim as new terrain.

Recent cases: Pisco

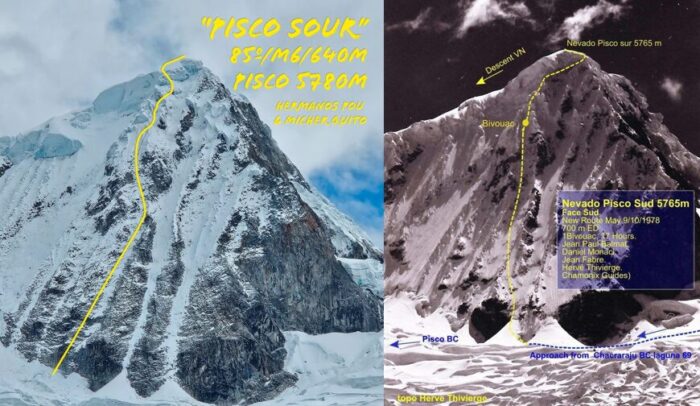

However, as pointed out before, it is often hard to determine whether two lines overlap exactly and for how long when conditions on a mountain change every year. Most teams claiming a new route do so in good faith, but may be unaware that someone was there earlier. Or they are convinced that their line really is different.

Let’s consider the M6 line that Eneko and Iker Pou of Spain and local guide Micher Quito climbed on Pisco, in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca. Shortly after the climbers published the details of their climb up a heavily crevassed glacier and which included some difficult mixed passages, a veteran French climber pointed out that he had opened that same line in 1973.

Topos of the routes climbed on the south face of Pisco in 2024, left, and 1978, right. Photos by Pou brothers and Heve Thivierge

The Spaniards, who have opened dozens of new lines in the Andes without previous conflicts, insisted their line was close to but not exactly in the same place, “except for perhaps a couple of pitches, and we are not even sure of that,” they said.

They also noted that the mountain has changed radically since 1973. Glacier movement and climate change have made it a much different and harder climb than in 1973. In the end, there was no agreement, and each party adhered to its own point of view.

2025 Nanga Parbat

Some months ago, Denis Urubko and Maria Cardell opened a new route on Pakistan’s Nanga Parbat. It was an epic climb done in alpine style and in dangerous conditions, with no one else on the mountain.

It has been widely acclaimed as one of the best expeditions of 2025. Cardell became the first woman to climb an 8,000m peak via a new route in alpine style. Denis Urubko is already recognized as one of the best high-altitude climbers ever, and his impressive resumé speaks for itself.

Maria Cardell on the summit of Nanga Parbat. Photo: Denis Urubko

Soon after Urubko and Cardell shared a preliminary topo, some commenters on social media noted that the new line was very similar to another route opened by Louis Rousseau of Canada and Gerfried Goschl of Austria.

Post on X on July 21.

Gerfried Goesch had perished on Gasherbrum I, but Urubko and Cardell were careful to speak to Louis Rousseau before their expedition, to make sure they climbed on different terrain.

Mapping the routes

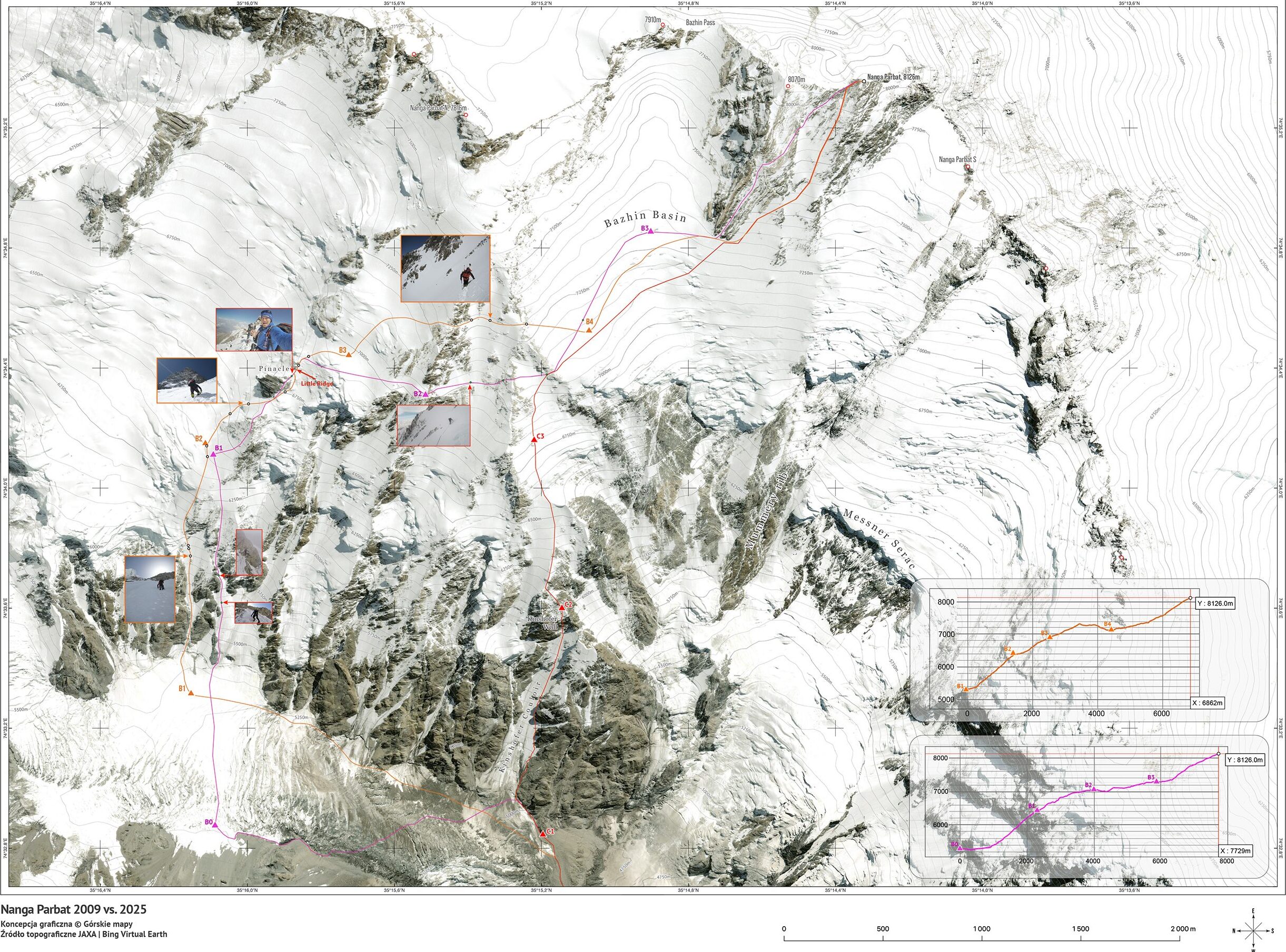

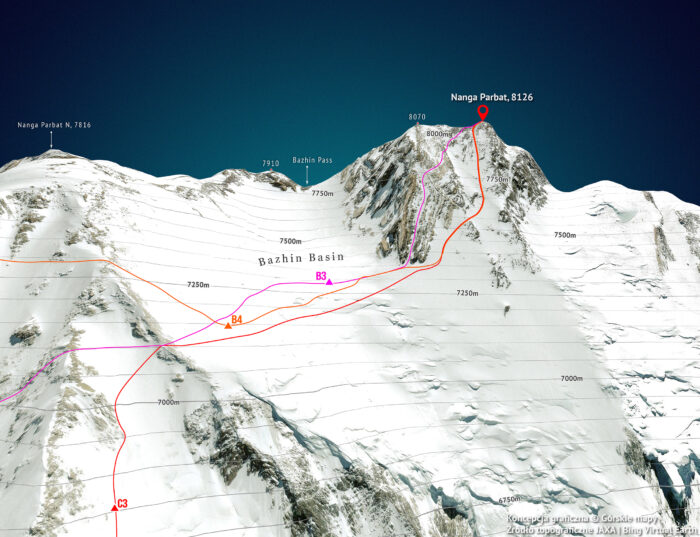

After the expedition, in order to clear up any questions, Urubko collaborated with Gorskie Mapy of Poland, whose exquisite cartographic work is a respected reference in mountaineering. Urubko provided testimonies, memories, and photos. He had no GPS or tracker during the climb.

Rousseau has also contributed to the work with details of his own 2009 summit. The result is as follows:

The lower part of the climb: The pink route is Urubko-Cardell’s; the orange line is Goeschl-Rousseau’s. Pictures and study by Gorskie Mapy

The area between 6,000 and 7,000m. Picture and study by Gorskie Maps

A tighter zoom from the previous image. The reddish line on the right, marked with C3 (Camp 3) is the classic Kinshoffer route. Picture and study by Gorskie Maps

The summit area. Picture and study by Gorskie Mapy

Urubko-Cardell’s route and Goeschl-Rousseau’s have different starting points. The closer areas are mid-mountain. Other sources told ExplorersWeb that the summit area is worth a careful look, since that is where most routes converge:

Picture shared on Facebook with several routes merging on the summit of Nanga Parbat from the Diamir side. From the book

The climbers speak

Since no official authority can resolve such fine points to everyone’s satisfaction, we asked two of the climbers affected: Louis Rousseau and Maria Cardell.

We originally spoke to Cardell shortly after she and Urubko climbed the route. “For a person not familiar with the terrain, it may look like it is the same line, but the distance between both routes is wide,” Cardell said. Everything else is speculation.”

Louis Rousseau deflects any controversy and instead highlights the style and conditions of the 2025 ascent.

Whether Urubko and Cardell’s route is a new route or a partial new line is not important. What is really important is that :

1) They made this ascent in an incredible style

2) They were only a team of 2

3) The conditions were dangerous, especially at the beginning of the route.

4) It’s the first time a woman alpinist climbed a route in such a style on an 8,000er.I will leave it to specialists and historians to judge if it’s a new line or a partial new line. For me, it’s just another incredible badass ascent made by Denis and Maria that embodied the true essence of alpinism.

As for Rousseau and Goeschl’s 2009 route, also done in excellent style and which includes a rescue of South Korean climber Mi-Sun Go, it deserves a separate story. We will write about it at some point.

Louis Rousseau, left, and Gerfried Goeschl on the summit of Nanga Parbat in 2009 after opening a new route. Photo: Louis Rousseau

Transparency first

U.S. climber Jack Tackle, chairman of the American Alpine Club’s Cutting Edge Alpine Grants committee and a jury at the Piolets d’Or for three consecutive years, told ExplorersWeb he is not familiar enough with Nanga Parbat to have an opinion on this specific issue. But in general, like the UIAA, he stresses the need to report honestly how a climb was done and which exact sections of the line include previously climbed terrain.

He mentions how Sam Hennessey, Robert Smith, and the late Michael Gardner reported their One Way Out route on the East Face of Alaska’s Mt. Hunter.

“The route we followed up the Diamond Arete is probably best described as a variation of the 1985 Tackle-Donini route,” Hennessey modestly told ExplorersWeb at the time, although his route runs on new terrain for approximately 650m.

Also, when the climbers rejoined the 1985 route, they found very different conditions than Jack Tackle and Jim Donini had.

The Diamond Arete on Mt. Hunter’s east face (Donini-Tackle, 1985) in yellow, and Hennessey-Gardner’s variation One Way Out (in red). Photo: M. Gardner/AAJ