In the 400s, the Western Roman Empire abandoned Britain to its own devices. Twin brothers Hengist and Horsa saw an opportunity to lead an Anglo-Saxon invasion and reshape England’s identity. But despite a legacy which echoes through southern England, many believe that the brothers never existed.

Hengist and Horsa’s story begins many decades before their arrival in 449 CE. The Western Roman Empire, a lesser incarnation of its mighty predecessor, faced an existential threat. Barbarian hordes were gradually taking Roman territory. At the same time, the empire’s political structure was becoming unstable, with a series of usurpers taking power.

With all this chaos at home, the Roman Empire saw Britain’s destiny as inconsequential. Local tribes, such as the Picts, were gradually reclaiming the island. This accelerated after the Empire abandoned Britain in 410 CE.

Britain was left to govern itself. Local aristocrats, warlords, landowners, and former Romans established their own polities.

An ally or a threat?

One ruler who emerged was called Vortigern, King of the Britons. Vortigern had the tricky task of dealing with bands of Picts from Scotland. Unable to subdue them, he sought help from Anglo-Saxon mercenaries. According to Bede, the English monk and so-called “father of English history,” who lived in the 700s:

It was unanimously decided to call the Saxons to their aid from beyond the sea. The first commanders are said to have been the two brothers Hengist and Horsa. They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vitta, son of Vecta, son of Woden; from whose stock the royal race of many provinces trace their descent.

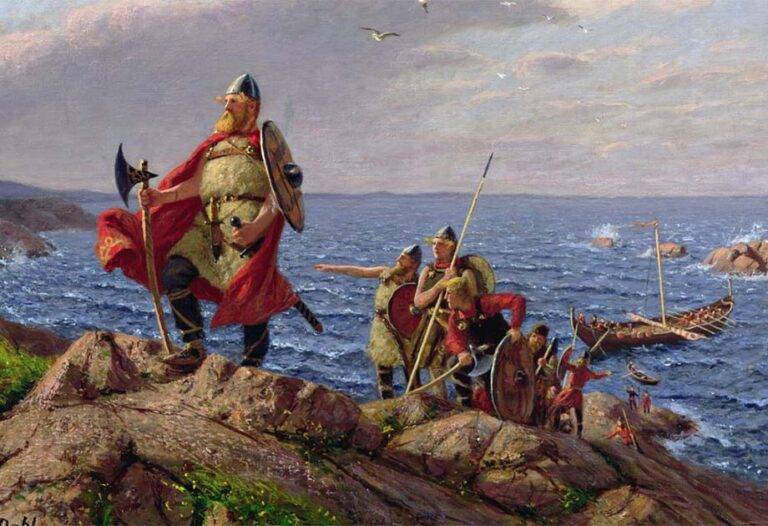

Hengist and Horsa were described as chieftains and direct descendants of Woden, the Anglo-Saxon god of war and wisdom. Some saw the brothers’ arrival on the Isle of Thanet in Kent as divinely ordained. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle explains how Vortigern granted the brothers land as a reward for their services:

In this year, Martianus and Valentinus succeeded to kingship, and ruled seven years. And in their days, Hengest and Horsa, invited by Vortigern, king of [the] Britons, came to Britain at the place which is called Ebbsfleet, first as a help to [the] Britons, but they afterwards fought against them. The king commanded them to fight against [the] Picts; and they did so, and had victory wherever they came.

In another version of the tale, told by Geoffrey of Monmouth, the brothers came to Britain on their own to offer themselves to Vortigern. It is worth noting that the History of the King of Britain was a pseudo-historical piece that included many fantastical elements. Hengist and Horsa’s story in this work included mythical characters such as Merlin and Aurelius Ambrosius.

Tensions rise

Vortigern allowed more Anglo-Saxons to come to Britain if they fought for him against the Picts. Thousands arrived and settled on the island.

Soon, tensions arose between the new arrivals and the locals. But Hengist had a plan. When the next wave of Saxons arrived, so did his beautiful daughter, Rowena. Vortigern fell in love with Rowena and asked for her hand in marriage. Hengist requested a fair exchange: Rowena for Kent. It sounded like a good deal, and the lovestruck Vortigern agreed.

Hengist gives Rowena to Vortigern. Photo: William Hamilton

However, peaceful relations soon soured. Vortigern’s son, Vortimer, resented his father’s alliance with the brothers. Soon, the two sides were at war and, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “Hengest and Horsa fought against Vortigern the king in the place which is called Aylesford; and Horsa was slain.”

When the troublesome Vortimer also died, Hengist and Vortigern brokered a peace over a feast. But Hengist planned to have his men murder Vortigern’s men. Vortigern, fearing for his life, handed over Essex, Sussex, and Middlesex to the Saxons.

The Anglo-Saxon reign in England had begun.

Parallels with other brothers

Romulus and Remus. Castor and Pollux. Ashvini Kumaras and Asvinau. These are some of the world’s most famous tales of brotherhood and the founding of kingdoms. Tales of divine twins were prevalent in Indo-European cultures and shared similar origin stories. Hengist and Horsa were descendants of Woden. Romulus and Remus were the sons of the god of war, Mars. Castor and Pollux were the sons of Zeus.

Romulus and Remus. Photo: Shutterstock

The names Hengist and Horsa both mean horse, and a white horse is the symbol of Kent. Horses were sacred, symbolizing dawn, kingship, and in some cases, the divine right to rule. The story of divine twins was a tool, providing legitimacy for new rulers.

But were they real?

Hengist and Horsa are mentioned in key texts such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, History of the Kings of Britain, the works of Bede, and even a couple of lines in Beowulf. Yet there’s no archaeological evidence to back up these references. However, there are some clues we can look into.

In the 1600s and 1700s, some people believed the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire (a huge carving of a horse into a hillside) was related to Hengist and Horsa. Thomas Baskerville (a topographer) and John Aubrey (an antiquarian) suggested an Anglo-Saxon origin. However, in 1995, a team from Oxford Archaeology dated the horse to the Bronze Age — much earlier. In his article The Scouring of the White Horse: Archaeology, Identity, and Heritage, American author Philip Schwyzer stated that the horse might have served as a familiar religious symbol for the Anglo-Saxons who settled in Britain.

In Kent, there are several structures located near Aylesford where Horsa is said to have died. The White Horse Stone is a megalith dating to the Neolithic period, but local folklore suggests that it is the site where Hengist and Horsa established their kingship, where they fought Vortigern.

Kit’s Coty House is another Neolithic structure that some people associate with Horsa or Cartigern (another of Vortigern’s sons), believing it is a burial site.

Apart from these few references, we have no other evidence of the brother’s existence.

Conclusion

Hengist and Horsa could have been based on real people, with the story of their divine background a way of legitimizing their invasion and settlement of Britain. However, without tangible evidence, Hengist and Horsa are more likely mythical figures.