This past summer, neuroscientists, anthropologists, philosophers, oceanographers, and Marshall Island navigators spent 40 hours at sea to understand how indigenous sailors sailed by “feeling the ocean.” Traveling between the atolls of the Marshall Islands, between Hawaii and Australia, the Marshallese sailors did not use GPS or sextants, but the ancient skill of wave-piloting.

For centuries, master navigators read the feel and sight of waves, the shift of swells, the movement of wind, and the motion of the canoe to sense islands over 50km away. The Marshall’s 29 atolls are all low-lying, often rising just a few feet above the waves. They are nearly invisible until you’re almost upon them.

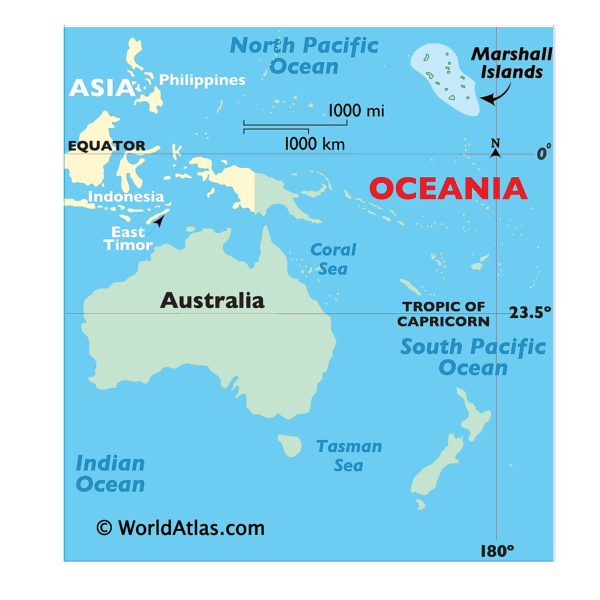

The Marshall Islands, upper right-hand corner. Image: World Atlas

The ancestral practice has nearly vanished. Between the 1940s and 1950s, the Marshall Islands were the site for U.S. nuclear tests. Entire communities were displaced, and with them, many traditional skills were lost.

A small group has tried to keep the tradition alive. A central figure in the current research is Alson Kelen, the director of a local canoe-building school. He was taught to wave-pilot by his cousin, Captain Korent Joe, one of the last fully trained master navigators.

Measuring brain activity. Photo: Chewy C. Lin

This joint project, involving University College London, the University of Stirling, the University of Hawaii at Hilo, and Harvard University, aimed to investigate what happens inside the brains of expert navigators as they read the ocean. Most navigation-based research focuses on land using city navigation, virtual environments, or controlled laboratory tasks. Navigation at sea is far harder, as there are almost no landmarks.

Second nature for Marshall Islanders

Over a two-day voyage this summer, researchers used mobile eye-tracking, 360° motion capture, heart rate and brain activity monitoring, and regular mapping tasks to collect data on how Marshallese sailors navigate the ocean. Every 30 minutes, everyone on board marked their perceived location on a map. They also noted from which direction the waves seemed to be coming.

For most, this was a bewildering challenge, but for the Marshallese sailors, it was second nature. Hugo Spiers, one of the lead scientists who has studied navigation for decades, admitted, “I found it extremely hard to know where I was.”

The 360° motion capture registered all the cues throughout the journey — the changes in swell, wind, clouds, and water. Meanwhile, the eye tracking and brain activity monitoring will help map what was happening in the brains of the navigators and which cues they were using.

The study used eye-tracking glasses. Photo: Chewy C. Lin

This study is not just academic. It hopes to pass on ancient cultural knowledge at a time when climate change and rising seas threaten the Marshall Islands.

The researchers will publish their findings next summer.