The Himalayan Database has updated its list of spring 2025 summits, both on 6,500m peaks and those above 8,000m.

Compared with previous years, the trend of everyone climbing the same few peaks at the same time continues. That’s good for the business but bad for lovers of empty spaces. However, alpine-style ascents have not gone away.

Overall, the spring 2025 numbers reveal some interesting trends.

Ama Dablam in the fall

Ama Dablam has become an autumn peak. Only 34 summits took place this past spring, compared to over 500 (!) during the previous autumn. Non-guided teams on Ama Dablam are now rare. Of the 505 summiters in the fall of 2024, 285 were foreigners, and 220 were guides or porters.

A crowded and precarious camp on Ama Dablam. Photo: Lakpa Sherpa/8K Expeditions

The usually stable weather in October and November allows for higher summit rates on peaks for trekkers. In addition, the monsoon blankets those trekking peaks with a thicker layer of snow. This allows easier progress, with fewer open crevasses and no hard ice.

In spring, most climbers head for the 8,000m peaks. They acclimatize by rotating up and down the normal route or on 6,000’ers such as Lobuche East and Imja Tse (Island Peak).

Climbers on Lobuche head for the east summit. Photo: Elite Exped

Few spring alpine-style climbs…

In that 2025 list that The Himalayan Database (THD) released this week, there were only three expeditions to other 6,000m and 7,000m peaks (not counting Ama Dablam), all by alpine-style teams. This includes Baruntse, summited by David Goetler of Germany and Tiphine Duperier and Boris Langenstein of France; Jugal 5, where Min Bahadur Lama was the only summiter; and Kabru Main (also called Kabru I) in the Kangchenjunga region, summited by the three-person team of Peter Hamor of Slovakia, and Nives Meroi and Romano Benet of Italy.

Nives Meroi on Kabru I. Photo: Romano Benet

Finally, there is a correction about Hernan Leal, Lhakpa Chhiri Sherpa, Ngata Sherpa, and Purnima Shrestha’s summit of one of the Sharpu peaks. THD corroborates ExplorersWeb’s earlier investigation, after the team claimed a first ascent of Sharpu IV. Their first ascent was, in fact, of Sharphu VI.

Fall is the time for new routes

Spring may belong mostly to the commercial teams, but many more teams go for new routes and first ascents in the fall, when conditions are better. As Billi Bierling of THD told ExplorersWeb, “The main trend I see is that the more that people go to the 8000’ers, the more the young alpinists (and the old ones like Mick Fowler and Victor Saunders) seek out new and interesting goals.”

Bierling also noted the impact of the jet stream in the fall.

“Spring is better for 8,000m peaks in the Nepal Himalaya, but it’s probably better to climb the lower mountains in the autumn, because the weather windows are longer,” she noted. “The jet stream also comes down to approximately 8,500m at the beginning of October, so it does not affect the 6,000’ers and 7,000’ers.”

King Everest

Everest remains the undisputed king of the spring season. High numbers flocked again to the Nepalese side of the mountain. The Tibetan side, now open to foreign expeditions again after a long COVID hiatus, saw significant action too.

Overall, it’s clear that the allure of Everest for the general public is far from fading. The number of permits remains steady on the South Side and continues to grow significantly on the North Side. Additionally, high summit rates are attracting more people, since summits are — while never guaranteed — increasingly likely.

On the South Side, climbing royalty fees are increasing in 2026 from $11,000 to $15,000. However, as we have noted in the past, the overall costs of a commercial climb on Everest are so high that an extra $4,000 won’t make a difference for most Everest clients.

The final number of permits for the South Side of Everest in 2025 was 371, a touch lower than the 421 from 2024.

The huge Base Camp by the Khumbu Glacier on the south side of Everest. Photo: Lakpa Sherpa/8K Expeditions

Another confirmed trend: the number of Nepalese staff on Everest now exceeds the number of foreigners. Counting both sides of the mountain, in 2024 there were 488 permits for foreigners, and 370 of them summited — a success rate of nearly 76%. That same year, 491 Nepalese summited Everest. They fixed ropes, guided or supported clients, or climbed on their own to increase their personal tally for their resumés.

In 2025, the total numbers were also impressive. The Department of Tourism issued 374 climbing permits for the South Side of Everest. A total of 272 foreigners and 437 Nepalese nationals reached the summit. One novelty: the latter number included nine Nepalese clients, climbing with their guides, also Nepalese.

Crowds at the Hillary Step, near the summit of Everest. Photo: Lakpa Sherpa/8K Expeditions

Rising numbers in the north

Everest’s North side grew more popular in 2025. The Himalayan Database registered 117 summits.

Such North Side figures double those from 2024, when just 56 foreigners climbed Everest from the Tibetan side. (Only five people who reached Base Camp didn’t stand on top.) However, those 117 summits were tiny compared to the 787 summits on the South Side in 2025.

There were no deaths on the North Side in either 2024 or 2025. Eight people died on the South Side in 2024 and five in 2025.

Climbers take the last steps to the summit of Everest from the North Side. Photo: @griffin_mims

Taking both routes together, THD has a total of 820 individual ascents but 852 ascents in all, highlighting the increasing number of guides who summit more than once in a season.

Chinese prefer Nepal

On the North Side of Everest in 2025, 28 Chinese citizens reached the summit from the North Col and the Northeast Ridge, but it is not clear if they were all clients or if some were guides. Interestingly, there were more Chinese citizens on the South Side of Everest: 68 Chinese received permits, making China the third most numerous nationality after India and the U.S. Fifty-one out of those 68 Chinese reached the summit.

Climbers at the North Col, Everest North side. Photo: Imagine Nepal

The reason why Chinese prefer to climb Everest from Nepal? It’s cheaper, there are more outfitters to choose from, and there are fewer demands for previous experience. In Tibet, everyone attempting Everest must have reached 8,000m previously.

Other 8,000’ers

On the other 8,000’ers, the percentages between foreigners and locals are about 50-50. Annapurna, for instance, registered 45 summits, 22 of them by Nepalese staff. On Dhaulagiri, 50% of the 14 summits were Nepalese guides. There were 40 summits on Makalu — 18 Nepalese and 22 foreigners.

The 8,000er most commonly summited, besides Everest, was Lhotse. This is not surprising, as many Everest climbers also do Lhotse before returning to Base Camp. In the spring of 2025, there were 102 summits on Lhotse, 55 Nepalese and 47 foreigners.

However, not counting this double-header peak, the 8,000’er most summited on its own, besides Everest, was Kangchenjunga. It had a total of 95 summits, 57 by Nepalese staff and 38 by foreigners.

Climbers on Kangchenjunga. Photo: Imagine Nepal

In addition to the five deaths on Everest, two Sherpas died on Annapurna, a French woman perished on Kangchenjunga, one Indian and one Romanian died on Lhotse, and one U.S. citizen perished on Makalu.

The grand totals

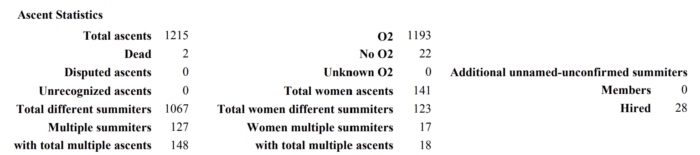

The chart below reflects the total number of ascents on Nepal’s 8,000’ers (including Everest from both Tibet and Nepal), and their characteristics, such as the male-female ratio and the increasing use of supplemental oxygen.

Data for Spring 2025 courtesy of The Himalayan Database.

Applicable to Pakistan?

The Himalayan Database only covers Nepalese peaks and nearby Cho Oyu, including those climbs from the normal route in Tibet. While the situation on Pakistan’s five 8,000m peaks differs slightly (scarce use of helicopters, more modest logistics, uncertain weather), the strong presence of Nepal-based companies in that country during the climbing season seems to confirm the upward trend.

Vinayak Malla of Nepal poses on the summit of K2 this summer. Photo: V. Malla