This year, Miriam Payne and Jess Rowe became the first all-female team to row nonstop across the Pacific Ocean. Starting in Lima, Peru, the British pair rowed 15,210km across the open ocean and landed in Cairns, Australia, 165 days later.

From the beginning, equipment failure and technical issues bedeviled the crossing. Only days after launching in April, their rudder failed completely, forcing them to abandon the attempt and catch a tow back to Lima. The setback cost them almost four weeks.

“That was particularly worrying,” they told ExplorersWeb, “because we needed to depart by a specific date to avoid the Australian hurricane season.”

It also triggered a financial scramble, as their spare rudder showed the same issue: “Peel ply left inside the rudder during construction allowed the foam core to expand and split the structure,” the pair explained.

New rudders had to be manufactured in the UK and flown to Peru at high cost.

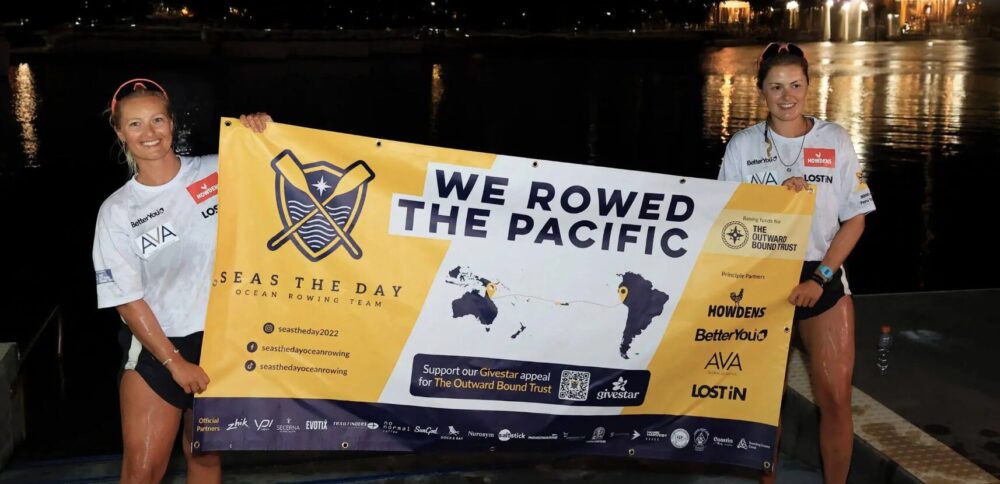

Photo: Seas the Day

Problems, problems

When they relaunched in early May, the problems continued almost immediately.

“We had problems with virtually every piece of equipment on board,” they admitted.

Their pipes of their electric watermaker burst, then the emergency watermaker failed, and they ended up replacing the filter with a pair of knickers. Soon after that, their electrical system began hemorrhaging power.

The power issues impacted the entire expedition. For almost the whole crossing, Payne and Rowe were forced into what they described as “ghost-ship mode.” Their batteries drained so fast that they had to shut down all non-essential systems.

“One by one, we had to shut everything down,” they said. “No AIS, no VHF radio, no chart plotter, no navigation lights, and even our radar reflector was turned off.”

They generated just enough electricity to briefly run the watermaker and charge their Garmin inReach to stay in contact with their safety officer and weather router. At times, even the autopilot failed.

“There were frequent occasions when we had to go completely dead ship and navigate using the stars or [the direction of] the wind on a small flag.”

Long days

Despite this, the pair managed to row 16 hours a day and average roughly 95km. The physical toll was relentless. Their hands were blistered, salt sores were endless due to the constant salt spray, and the cabin was so hot it was nearly impossible to sleep. Still, their mindset remained remarkably positive.

“We genuinely enjoyed the rowing,” they said. “The conditions were constantly changing, and there was always something to talk about. No two days were ever the same, and we felt incredibly lucky to be out there.”

Their Pacific expedition followed earlier success in The World’s Toughest Row across the Atlantic, but the two experiences could not have been more different.

“The Atlantic was a race,” they explained. “It was much more intense but over far quicker.”

They had rowed in separate boats and encountered no major technical issues. The Pacific, by contrast, was an entirely independent expedition.

“When we took part in the Atlantic rowing race, everything was organized for us,” they recalled. “We were told what equipment to bring, how much food to pack and exactly where to start and finish. For this expedition, none of that was clear. We had to figure out the start and end points ourselves and carry out extensive research to build a workable plan.”

Photo: Seas the Day

Two years of prep

They started planning their Pacific row almost immediately after completing their Atlantic crossing. Both felt a real sense of sadness after the initial elation at making it across the Atlantic to Antigua, and conversation turned to what they could do next. Everything they looked at was smaller than what they had already done, and they wanted to go bigger.

The obvious choice was to enter the sister race run by The World’s Toughest Row that crosses the Pacific from San Francisco to Hawaii.

“But we felt that rowing only a third of the ocean wasn’t enough. That’s when the idea emerged: to see whether it was possible to row the entire Pacific Ocean nonstop and unsupported,” they explained.

For Rowe and Payne, the toughest part of this row was the two years of preparation. They worked with a weather router to find viable start and end points. They had to figure out how to get a boat and all their supplies to Peru, and trained with specialist coaches to ensure they were ready for the physical demands of the row.

“It takes a huge amount of self-discipline and determination,” they told us. “Every spare hour outside full-time work was spent training, fundraising for sponsorship, or working on the boat. It’s an enormous commitment that demands real sacrifice. For both of us, that meant no social life and very little time with family throughout the two years.”

Unknown endpoint

As they set off, their only goal was to reach the Australian coast. Brisbane appeared on their tracker simply because a location had to be selected, but their actual endpoint was unknown for most of the row.

“We never had a fixed endpoint,” they explained. “It wasn’t something that we could decide until we were about 1,600km out.”

In the end, winds and currents pushed them north to Cairns. “With the weather conditions we had, heading further south just wasn’t possible.”

The final few weeks were particularly tough. In the Coral Sea, headwinds pushed them southeast, forcing them to work constantly to avoid being blown toward Papua New Guinea. Substantial waves crashed over the side of the boat, which worsened their salt sores. Soaring temperatures left them with prickly heat. As they hit Australia’s east coast, they had to contend with busy shipping lanes.

Photo: Seas the Day

Brutal final hours

However, there was one small breakthrough. As the ozone layer over Australia is a little thinner, their batteries could charge more efficiently. For the first time in months, they intermittently powered up their chart plotter. It was a huge boost, especially while trying to navigate across the Great Barrier Reef in the dark.

The final approach to Cairns was the hardest of all. “Those final four hours were brutal,” Rowe said. “We were battling 20-knot headwinds and being pushed further and further out of the channel.”

At one point, they genuinely believed they might fail within sight of land. “We honestly thought we weren’t going to make it. We thought we might have to swim to shore — an unsettling prospect given the crocodiles and sharks in the water!”

Photo: Seas the Day

Focused on solutions

The two women came up against near-constant issues, but for the most part did not need to try hard to motivate themselves. They stayed solution-focused when problems arose, because “nothing good ever comes from panicking or being negative.”

They treated themselves to chocolate, listened to audiobooks, had Abba sing-alongs, and reveled in the world around them.

“Seeing the whales was incredible,” they said. “The night sky was unforgettable — the Milky Way stretched above us, and when we rowed, the paddles lit up the phosphorescence in the water. It felt completely otherworldly.”

A few months later, they are still adjusting to being back on land.

“We’ve lost a significant amount of muscle, and we’re still extremely tired,” they said.

For both, sleep remains an issue. “After being so accustomed to functioning while sleep-deprived, it’s been hard to reset. We’re still averaging only about five hours a night, even after two months back on land.”