“Death is not the end. There remains the litigation over the estate,” wrote the sardonic writer Ambrose Bierce. Bierce was unafraid of death; in fact, he welcomed it with open arms and a good punchline. In 1913, he figured he might meet death during the Mexican Revolution while following Pancho Villa’s forces as they fought the Constitutionalists. He disappeared. Did he receive his grim wish, and if so, how?

Background

Bierce’s childhood was not conventional. He was the second-to-last of 13 children, whose names all started with the letter “A.” Although his family struggled to make ends meet, he received a good education and developed a passion for the arts. He fell in love with writing and became an apprentice at a print shop as a teenager. However, although he could have made a decent living in publishing, he was fond of action.

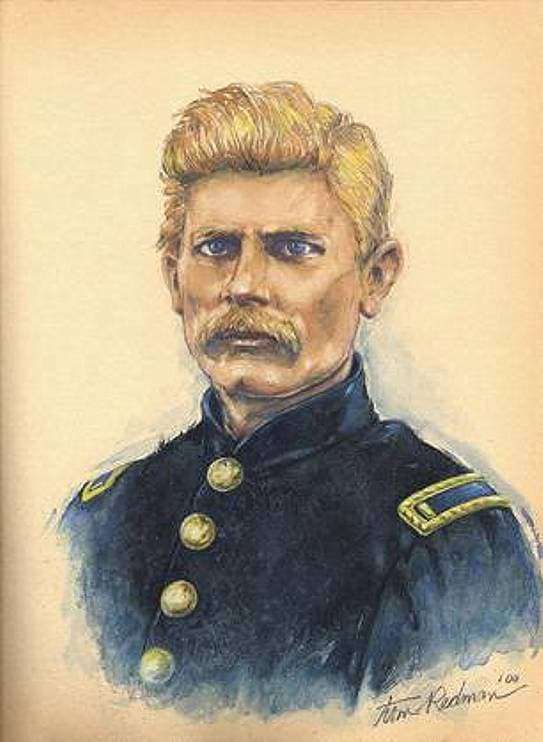

Bierce became an exceptional soldier after enlisting in a military school in Kentucky. He fought for the Union during the American Civil War and received recognition for his valor. The army later sent him to West Point for further instruction. Yet his bright future as an officer came to an abrupt halt when he suffered a horrific brain injury, forcing him to leave the army. This trauma broke something inside him. No longer was Bierce the regimented, disciplined, and idealistic soldier fighting for love of his country. A dark shadow settled over him.

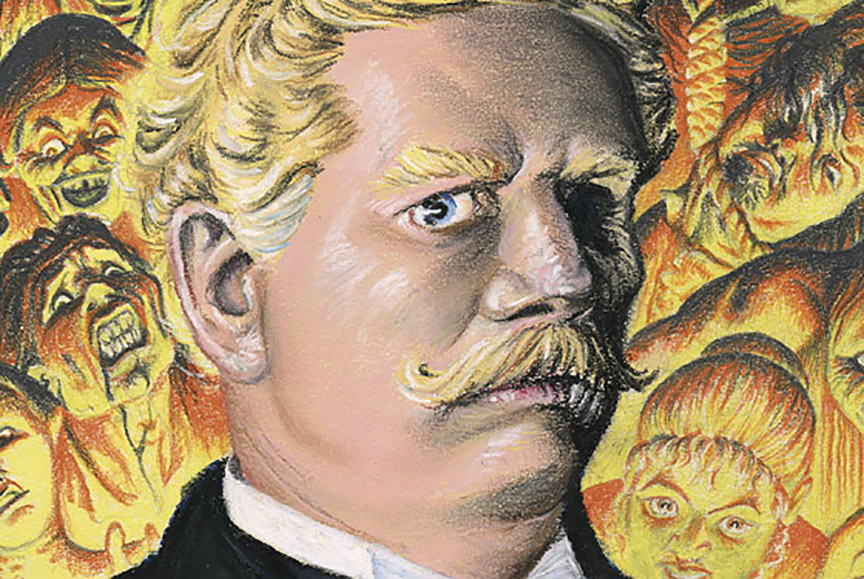

Ambrose Bierce during his soldiering years. Illustration: Tom Redman

A new way of life

His second love, writing, offered a glimmer of hope.

Bierce was a literary non-conformist, finding his voice in satire and social commentary while writing for publications in San Francisco, where he chose to settle. His popular works, like An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and Chickamauga, are critical of war and highlight the hypocrisy of those who glorify it. He also wrote horror stories briefly, earning praise from H.P. Lovecraft.

But his magnum opus was The Devil’s Dictionary, a satirical glossary considered one of the great works of American literature. To give you some insight into Bierce’s personality, here’s a definition of the word love from this work: “Love (n.) A temporary insanity curable by marriage.” Little wonder that contemporaries called him Bitter Bierce.

The book was a massive hit, but behind closed doors, Bierce was drowning.

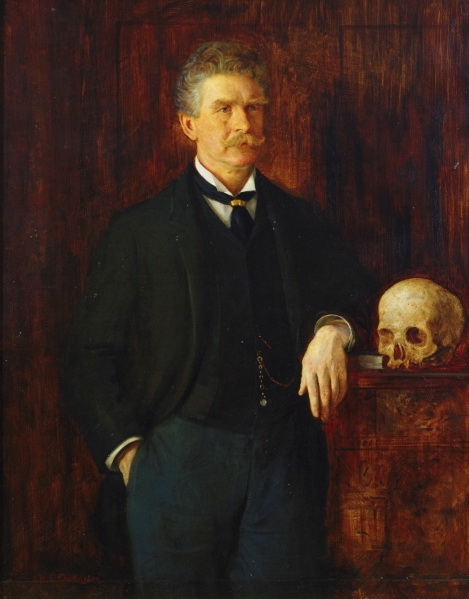

Ambrose Bierce and a skull. Photo: J.H.E. Partington

Behind the satire was a broken and nihilistic man. His two sons died, one from suicide and the other from alcoholism. He and his wife had divorced after she had an affair, and soon after, she passed away.

After these personal tragedies, Bierce renounced his belief in God and said he was simply waiting for an opportunity to die. In 1913, at the age of 71, he decided to investigate the Mexican Revolution. Perhaps he’d found his opportunity.

Letters or suicide notes?

His letters to relatives speak for themselves, opening a window to his tortured soul. American author Bertha Clark Pope published the Letters of Ambrose Bierce, highlighting a newspaper clipping that he sent to his niece, which says:

‘I’m on my way to Mexico, because I like the game,’ he said, ‘I like the fighting; I want to see it. And then I don’t think Americans are as oppressed there as they say they are, and I want to get at the true facts of the case.

‘Of course, I’m not going into the country if I find it unsafe for Americans to be there, but I want to take a trip diagonally across from northeast to southwest by horseback, and then take a ship to South America, go over the Andes and across that continent, if possible, and come back to America again.

‘There is no family that I have to take care of; I’ve retired from writing and I’m going to take a rest. No, my trip isn’t for local color. I’ve retired just the same as a merchant or businessman retires. I’m leaving the field for the younger authors.’

Along with this clipping, he also said that “if you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags, please know that I think that a pretty good way to depart this life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stairs. To be a gringo in Mexico — ah, that is euthanasia!”

Bierce wrapped up his life in the United States, organizing copyrights of his work and saying goodbye to those he knew. En route to Mexico, he stopped at the battlefields he had fought on.

Pancho Villa. Photo: Library of Congress

What happened in Mexico?

Late in 1913, Bierce crossed into Mexico during the Revolution’s bloodiest phase. Summary executions were normal, and alliances were volatile. Bierce sought a front-row seat and attached himself to Pancho Villa’s forces, observing battles like a war tourist.

Bierce barely knew any Spanish, and his last letter, sent from Chihuahua on December 26, said he was heading to an “unknown location.” This was the last anyone heard from him.

Theories

As an American wandering into a war zone in a foreign country, many believe Bierce was probably killed as a suspected spy. This theory was pushed by a former mercenary named Tex O’Reilly, who claimed that Bierce was shot in a cemetery.

Another theory portrays Bierce as angering Pancho Villa and possibly cozying up to his enemy, Carranza. Writer Vincent Starrett investigated Bierce’s disappearance and came across some information that suggested Bierce was executed in 1915, two years after his correspondence ceased.

In a Washington Times article dated April 27, 1919, a different author references an American accompanying a Mexican convoy who was captured by a general named Tomas Urbina. The convoy was allegedly en route to a Constitutionalist camp, and Bierce was supposedly executed.

However, oral tradition in Sierra Mojada in northeastern Mexico suggests Pancho Villa executed Bierce.

Some people believe Bierce didn’t die in Mexico, but in Texas. There’s an obscure claim from a man who said he picked Bierce up beside the road. Bierce apparently called himself Ambrosia, was carrying The Devil’s Dictionary, and was very sick. This story states that Bierce died in Marfa, Texas, in 1914.

Meanwhile, author Dan Sheehan of Literary Hub believes Bierce may have gone out into the Grand Canyon and died “on his own terms.”

Conclusion

It seems that for years after his disappearance, Ambrose Bierce died several deaths. Newspapers churned out new theories and new sources. Whether by execution or suicide, Bierce got what he wanted in the end.

Illustration: Centipede Press