BY LUDOVIC SLIMAK

Today, as Greenland once again becomes a strategic prize, history seems poised to repeat itself. Staying with the Polar Inuit means refusing to speak of territory while erasing those who inhabit it.

On June 16, 1951, Jean Malaurie was traveling by dog sled along the northwest coast of Greenland. He had set out alone, almost on a whim, with a modest grant from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), officially to study periglacial landscapes. In reality, this encounter with people whose relationship with the world followed an entirely different logic would shape a singular destiny.

That day, after many months among the Inuit, at the critical moment of the spring thaw, Malaurie was traveling with a few hunters. He was exhausted, filthy, and emaciated. One of the Inuit touched his shoulder: “Takou, look.” A thick yellow cloud was rising in the sky. Through his binoculars, Malaurie first thought it was a mirage:

“A city of hangars and tents, of metal sheets and aluminum, dazzling in the sunlight, amid smoke and dust…Three months earlier, the valley had been calm and empty of people. I had pitched my tent there, on a clear summer day, in a flowering, untouched tundra.”

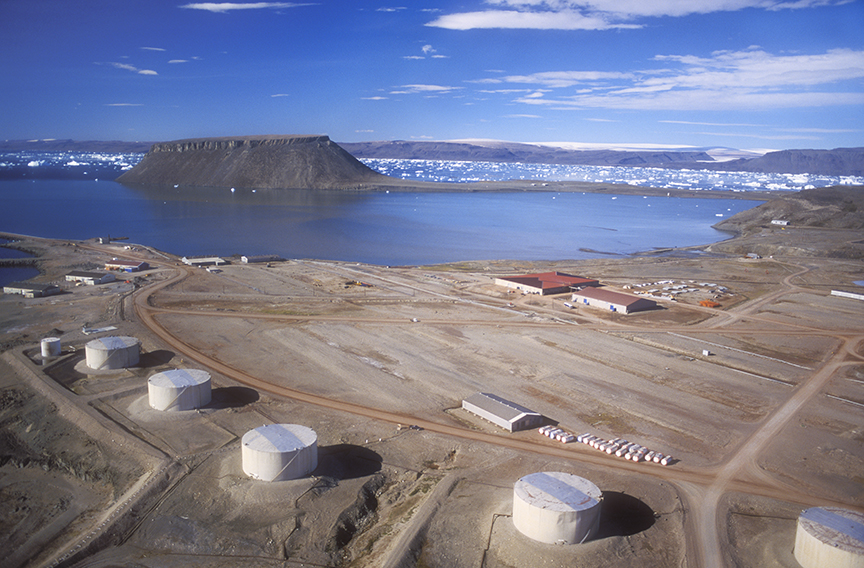

Operation Blue Jay

The breath of this new city, he later wrote, “would never let us go.” Giant excavators hacked at the ground, trucks poured debris into the sea, aircraft circled overhead. Malaurie was hurled from the Stone Age into the Atomic Age. He had just discovered the secret American base of Thule, codenamed Operation Blue Jay.

The American base at Thule in the early 1950s. U.S. Army, The Big Picture — Operation Blue Jay (1953), CC BY

Behind this innocuous name lay a colossal logistical operation. The United States feared a Soviet nuclear attack via the polar route. In a single summer, some 120 ships and 12,000 men were deployed to a bay that had previously known only the silent glide of kayaks. Greenland’s population at the time numbered barely 23,000 people. In just 104 days, on permanently frozen ground, a technological city capable of hosting giant B-36 bombers carrying nuclear warheads emerged. More than 1,200 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, and in almost total secrecy, the United States built one of the largest military bases ever constructed outside its continental territory. A defense agreement was signed with Denmark in the spring of 1951, but Operation Blue Jay was already underway: the American decision had been taken in 1950.

Thule Air Base. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

The Inuit world

Malaurie immediately grasped that the sheer scale of the operation amounted, in effect, to an annexation of the Inuit world. A system founded on speed, machinery, and accumulation had violently and blindly entered a space governed by tradition, cyclical time, hunting, and waiting.

The blue jay is a loud, aggressive, fiercely territorial bird. Thule lies halfway between Washington and Moscow along the polar route. In the era of intercontinental hypersonic missiles, once Soviet and now Russian, it is this same geography that still underpins the argument of “vital necessity” invoked by Donald Trump in his calls to annex Greenland.

The Thule base has a strategic position between the USA and Russia. U.S. Army, The Big Picture — Operation Blue Jay (1953), CC BY

The most tragic immediate outcome of Operation Blue Jay was not military, but human. In 1953, to secure the perimeter of the base and its radar installations, authorities decided to relocate the entire local Inughuit population to Qaanaaq, roughly 100 kilometers further north.

The displacement was swift, forced, and carried out without consultation, severing the organic bond between these people and their ancestral hunting territories. A “root people” was uprooted to make way for an airstrip.

It is this brutal tipping point that Malaurie identifies as the moment when traditional Inuit societies began to collapse. In these societies, hunting is not merely a survival technique but an organizing principle of the social world.

The Inuit universe is an economy of meaning, made of relationships, gestures, and transmission through the generations that confer recognition, role, and place in relation to each individual. This intimate coherence, which constitutes the strength of these societies, also renders them acutely vulnerable when an external system suddenly destroys their territorial and symbolic foundations.

Collapse of traditional structures

Today, Greenlandic society is largely sedentary and urbanized. More than a third of its 56,500 inhabitants live in Nuuk, the capital, and nearly the entire population now resides in permanent coastal towns and settlements.

Housing reflects this abrupt transition. In the larger towns, many people live in concrete apartment blocks built in the 1960s and 1970s, often deteriorating and overcrowded. The economy is heavily dependent on industrial fishing geared toward export. Subsistence hunting and fishing are still commonplace.

Modern rifles, GPS devices, snowmobiles, and satellite connections now work hand in hand with old habits. Hunting remains a marker of identity, but it no longer shapes either the economy or intergenerational transmission.

The fallout on a human level from this shift is massive. Greenland today has one of the highest suicide rates in the world, particularly among young Inuit men. Contemporary social indicators, such as suicide rates, alcoholism, and domestic violence, are widely documented. Many studies link them to the speed of social transformation, forced sedentarization, and the breakdown of traditional systems of transmission.

American military maneuvers at Thule. U.S. Army, The Big Picture — Operation Blue Jay (1953), CC BY

The thermonuclear accident

The logic underpinning Thule reached a point of no return on January 21, 1968. During a continuous nuclear alert mission, a US Air Force B-52G bomber under the Chrome Dome program, crashed into the sea ice some ten kilometers from Thule. It was carrying four thermonuclear bombs. The conventional explosives designed to initiate the nuclear reaction detonated on impact. There was no nuclear explosion, but the blast scattered plutonium, uranium, americium, and tritium over a vast area.

In the days that followed, Washington and Copenhagen launched Project Crested Ice, a large-scale recovery and decontamination operation ahead of the spring thaw. Around 1,500 Danish workers were mobilized to scrape the ice and collect contaminated snow.

Decades later, many of them initiated legal proceedings, claiming they had worked without adequate information or protection. These cases continued until 2018–2019 and resulted only in limited political compensation, without any legal recognition of responsibility. No comprehensive epidemiological study has ever been conducted among the local Inuit populations.

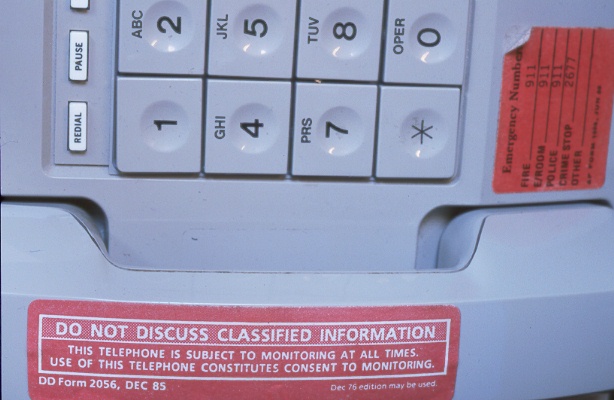

Now renamed Pituffik Space Base, the former Thule base is one of the major strategic nodes of the U.S. military apparatus. Integrated into the U.S. Space Force, it plays a central role in missile warning and space surveillance in the Arctic, under maximum security conditions. It is not a relic of the Cold War, but an active pivot of contemporary geopolitics.

Phone at Thule Air Base. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

More of the same

In The Last Kings of Thule (1953), Malaurie shows that indigenous peoples have never had a place at the heart of Western strategic thinking. Amid the great maneuvers of the world, Inuit existence becomes as peripheral as that of seals or butterflies.

Donald Trump’s statements do not herald a new world. They seek to generalize a system that has been in place in Greenland for 75 years. Yet the position of one man cannot absolve us of our collective responsibilities. To hear today that Greenland “belongs” to Denmark and therefore falls under NATO, without even mentioning the Inuit, is to repeat an old colonial gesture: conceiving territories by erasing those who inhabit them.

Portrait of a Greenland Inuk. Popular Science Monthly Volume 37

The Inuit remain invisible and unheard. Our societies continue to imagine themselves as adults facing infantilized, indigenous populations. Their knowledge, values, and ways of being are relegated to secondary variables. Difference does not fit within the categories that our societies know how to handle.

The Inughuit from Thule were relocated to a new settlement called Qaanaaq, above. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Following Jean Malaurie, my own research approaches humanity through its margins. Whether studying hunter-gatherer societies or what remains of Neanderthals once stripped of our projections, the “Other” remains the blind spot for our perceptions. We fail to see how entire worlds collapse when difference ceases to be thinkable.

Malaurie ended his first chapter on Thule with these words:

“Nothing was planned to imagine the future with any sense of elevation.”

What must be feared above all is not the sudden disappearance of a people, but their silent and radical relegation within a world that speaks about them without ever seeing or hearing them.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.