Of the 891 people who have summited 8,485m Makalu, only two have done so in winter.

Here, we’ll cover those winter successes, failures, and tragedies, but first, let’s review the overall climbing history of this fifth-highest mountain in the world. Frenchmen Lionel Terray and Jean Couzy first summited it on May 15, 1955, followed by six more over the next two days. All used supplemental oxygen

Marjan Manfreda, 25, of the former Yugoslavia, made the first no-O2 ascent on Oct. 6, 1975, via the South Face. He did not intend a no-O2 ascent, but his gear malfunctioned. His six companions, led by Ales Kunaver, used bottled O2.

Between 1950 and 1964, all 14 of the 8,000’ers were climbed for the first time, but none in winter. The first winter 8,000m ascent took place on Everest: On Feb. 17, 1980, Leszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielicki of Poland summited with supplemental O2.

On Feb. 9, 2009, Denis Urubko and Simone Moro topped out on Makalu. This made Makalu the ninth 8,000m peak climbed in winter, after Everest, Manaslu, Dhaulagiri I, Cho Oyu, Kangchenjunga, Annapurna I, Lhotse, and Shisha Pangma. Thanks to detailed expedition reports, we get a taste of how hard it is to climb an 8,000m peak in winter.

Makalu. Photo: Archil Badriashvili

Early winter attempts

Before the first success, 13 expeditions tried and failed to climb Makalu in winter.

In the winter of 1980-81, an Italian-Swiss expedition led by Renato Casarotto tried via the southeast ridge, without supplemental oxygen. On Jan. 23, 1981, Romolo Nottaris reached 7,350m before extreme conditions halted his progress. According to The Himalayan Database, it was -48ºC at 7,200m, with heavy snow and strong winds.

Fierce wind is a recurring theme on Makalu. The 1981 team recalled that the wind often blew at 200kph, shifting directions from south to north and destroying all seven Italian tents. Wind on the ridge was so strong that movement without fixed ropes was impossible.

British attempt

On November 30, 1981, the British Himalayan Winter Expedition arrived at Makalu Base Camp, led by Ron Rutland. The six-man party aimed to ascend the Makalu La–Northwest Ridge route (normal route) without bottled oxygen. The expedition started off poorly, with porters refusing to go higher because of a lack of snow, leaving the climbers to carry loads.

Linda Rutland, Alan Deakin, Bill Ryan, and Ron Rutland reached 7,255m on December 19 and left gear at the campsite. Extreme cold on the mountain (-50ºC) and strong westerly winds slowed the team’s progress to a crawl. On December 21-22, Rutland went up again, reaching 7,315m. The team didn’t make it any higher. The climbers were exhausted and suffered from altitude sickness. On December 28, they left the mountain.

Night on Makalu. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

The first winter solo attempt

In January 1982, Italian-French climber Ivano Ghirardini made the first solo winter attempt.

Ghirardini is a legendary solo climber. Before Makalu, he made the first successful winter solo trilogy of the great North Faces of the Alps (the Grandes Jorasses, the Matterhorn, and the Eiger). He did the first and only ascent of Mitre Peak, solo, in alpine style. He also climbed Aconcagua’s South Face solo. Finally, Ghirardini was a member of the French national expedition to K2, where he bivouacked alone at 8,350m without oxygen, during a solo attempt.

Ghirardini aimed to summit Makalu via the difficult West Pillar, alone and without bottled oxygen. Because of extreme cold and strong winds, he didn’t manage to summit. However, it was an amazing effort. He climbed alpine-style with just 120m of rope and a 25kg backpack. He reached 7,000m despite hurricane-force winds and -50˚C temperatures.

“The big problem in winter is the wind; snow and rock conditions are good,” Ghirardini said. “There is clear weather on many days, there are few avalanches, but very short periods of no wind. The wind sounds like a Boeing.”

The wind was at least 150kph and blew the rope horizontal, so he couldn’t rappel down to 7,000m. After this attempt, Ghirardini gave up extreme alpinism.

The West Pillar of Makalu. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

‘Snow-swimming’

In December 1985, a Japanese party led by Hiroyuki Baba aimed for the Makalu La- Northwest Ridge route without bottled oxygen. During their attempt, the wind snapped four tent poles, and their base camp tent blew away.

In their opinion, the route was easy, but the constant strong winds made progress impossible. Two climbers reached their highest point at 7,520m on December 23 but descended directly to Base Camp the next day. The team made no further attempts. Deep snow made the retreat difficult; it was like “snow-swimming,” they said.

That same winter, an Italian-Austrian-French party led by Reinhold Messner attempted the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route, also without O2. They reached 7,500m before strong winds forced them to abandon the climb.

In 1986, Japanese climbers Noboru Yamada and Yasuhira Saito attempted the Southeast Ridge without oxygen. On December 9, the duo abandoned their attempt at 7,500m due to bad weather, exhaustion, and a lack of food.

File image of Makalu’s upper sections, shot in the spring of 2025. Photo: Saulius Damulevicius

More wind

The Polish Winter Makalu Expedition in 1987-88, led by Andrzej Machnik, attempted the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route (again, without bottled oxygen). Like the Japanese team, they reached 7,500m before the wind stopped them.

In the winter of 1990, another no-O2 party, led by renowned Polish climber Krzysztof Wielicki, reached 7,300m on the West Pillar. On December 20, they reached 7,400m on the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route.

In January 1997, a no-O2 Spanish team, led by Manuel Gonzalez Diaz, attempted the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route. They reached a high point of 7,200m three times. Again, it was impossible to reach Makalu La because of the wind. Camp 1 blew away twice, including once when the wind moved a tent in Camp 1 — with three people inside — some distance sideways. It was windy every day, with gusts of over 100kph, for 45 days. On February 6, they abandoned the attempt.

In the winter of 2000-01, Wielicki returned again. This team reached 5,800m on the West Pillar, 6,400m on the South Pillar-South Col route, and 7,100m on Makalu’s northwest side on January 7. Likewise, they abandoned the attempt because of strong winds.

Makalu from the west. Photo: Ben Tubby

The first winter death on Makalu

French mountaineer Jean-Christophe Lafaille became the first to die on a Makalu winter expedition.

In January 2006, Lafaille was attempting the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route alone without supplemental oxygen. Before his solo expedition, he had already summited 11 8,000’ers, often solo or by new routes. He was also well known for a self-rescue on Annapurna’s South Face in 1992 after his climbing partner, Pierre Beghin, died.

Lafaille arrived on the mountain in late 2005 and spent weeks ferrying loads. After the wind forced several retreats, Lafaille resumed climbing on January 24 after the weather improved. On January 26, he established a high camp at 7,600m, pitching a small tent. Lafaille’s last communication was a satellite phone call to his wife at 4:30 am on January 27. He reported feeling good despite a lack of sleep from the altitude and the cold (down to -30ºC). He said he would push for the summit that day.

Helicopter searches found only a tent, and high winds limited higher flights. His wife, brother, and Finnish climber Veikka Gustafsson (who knew the route) participated in search efforts. They left supplies at Base Camp in case he returned.

Later, in the spring of 2006, an Italian expedition spotted a small red tent at 7,600m and a broken tent near a serac at 7,800m. It was too dangerous to approach the tents. Lafaille’s body was never found.

Experts, including Gustafsson, believe Lafaille likely fell into one of the route’s many treacherous crevasses (Gustafsson fell into three on the same route). Winds were not extreme during Lafaille’s final push, according to the weather forecasts.

This month marks the 20th anniversary of Lafaille’s death. (We recommend reading our detailed account of the incident: Flashback: Lafaille’s Death on Winter Makalu.)

The final photo of Jean-Christophe Lafaille, taken at 7,000m on winter Makalu. Photo: Jean-Christophe Lafaille

Further attempts

Two years after Lafaille’s disappearance, a small Italian team attempted the same route, again without bottled oxygen. Nives Meroi, Romano Benet, and Luca Vuerich arrived at Base Camp on January 13, 2008. They reached their highest point (7,000m) on January 28. The trio reported constant strong winds, and only two days (January 16 and January 27) without extremely blustery conditions.

The team left Base Camp on February 11 and retreated to a camp near Barun Pokhari. Between the two camps, the wind toppled Meroi, who broke her right ankle. Benet and Vuerich had to carry Meroi over the difficult moraine the rest of the way. A helicopter evacuated the team to Kathmandu on February 12.

That same winter, a Kazakh team also attempted Makalu. Denis Urubko, Gennadiy Durov, Sergey Samoilov, and Evgeny Shutov were on the same route (Makalau La- Northwest Ridge) without bottled oxygen. After establishing Base Camp at 5,600m, they rotated to higher camps. However, illness sidelined Durov, and poor acclimatization forced Samoilov to turn back at 7,200m during a period of good weather.

On February 1, Urubko, Samoilov, and Shutov reached Makalu La at 7,400m but were met with severe winds. Urubko reported that they were being blown several meters while roped together. They spent a precarious night at approximately 7,350m on a small ledge before attempting to continue on February 2. Soon after, gale-force winds up to 120kph made further progress impossible. They descended to Base Camp.

Simone Moro approaches Makalu’s summit. Photo: Denis Urubko/Simone Moro

The first winter ascent

In January 2009, Urubko returned to Makalu, this time with Italian Simone Moro. Without bottled oxygen, they completed the first winter ascent by focusing on speed and wind protection.

On January 20, the duo established their base camp at 5,680m in a gully near the Chago Glacier to shield themselves from the elements. Their acclimatization was rapid. They used a level area of the glacier for an initial bivouac at 6,100m before setting up Camp 2 at 6,800m on a steeper section.

Rather than following the traditional, sunnier route to the Makalu La, the pair opted for a direct couloir. While colder, this route offered better wind protection and allowed for faster movement. After a reconnaissance climb to 7,350m and shifting some gear, they launched their summit push on February 7.

The duo moved efficiently, bivouacking at 6,800m and then at 7,600m. On February 9, Urubko and Moro reached the summit in the early afternoon despite wind speeds of 120kph. They maintained a constant rope connection for safety. Racing against an approaching hurricane, they descended to Base Camp by February 10, collecting their gear before the storm hit.

After 13 failed winter expeditions to climb Makalu, Urubko and Moro had finally succeeded.

Simone Moro’s summit photo on winter Makalu. Photo: Denis Urubko/Simone Moro

The 2024 commercial guided attempt

The first commercial winter attempt was organized by Makalu Adventure in 2024. This expedition was the first to use bottled oxygen on a Makalu winter attempt. The team — composed of Sanu Sherpa, Iranian client Abolfazl Gozali, Pastemba Sherpa, and Sanu’s brother Phurba Ongel Sherpa — chose the Makalu La-Northwest Ridge route. They reached 7,900m on Jan. 26, 2025, before bad weather halted them.

A claimed second winter ascent, and tragedy

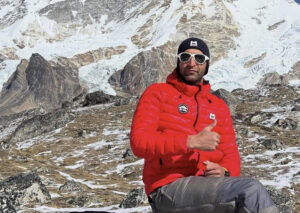

This winter, Makalu Adventure again organized a commercial guided winter expedition. Sanu Sherpa led clients Abolfazl Gozali of Iran and Piyali Basak of India (who had nearly died on Makalu in 2023), along with a strong group of Sherpas, including Phurba Ongel Sherpa (Sanu’s brother), Lakpa Rinjin Sherpa, and others.

The Sherpas were all experienced on 8,000m peaks, while Gozali had only summited Manaslu as a guided client in 2022 with bottled oxygen. However, Gozali had completed the Snow Leopard 7,000’ers.

The expedition reached Base Camp in early January 2026, fixed ropes, and prepared for a summit push amid typical winter challenges like high winds and cold.

Abolfazl Gozali during his winter Makalu attempt in 2025. Photo: Abolfazl Gozali

On January 15, Makalu Adventure reported that Sanu Sherpa, Abolfazl Gozali, Phurba Ongel Sherpa, and Lakpa Rinjin Sherpa reached the summit. However, the achievement was immediately overshadowed by tragedy during the descent. Phurba Ongel Sherpa fell to his death from above Camp 4 at approximately 7,500m, and Abolfazl Gozali went missing between Camp 4 and Camp 3.

We don’t know what happened to Abolfazl Gozali. He might have taken a wrong turn while descending toward Camp 3, or he may have fallen into a crevasse. Extreme winds and dangerous conditions hampered rescue teams (and Sanu Sherpa was injured during one search attempt), and the search was eventually called off on January 22. They had found no trace of Gozali, and Phurba Ongel Sherpa’s body was left on the mountain.

As of late January 2026, no summit photographs or other evidence have been publicly shared by the surviving team members or the expedition organizer.

File image of Phurba Ongel Sherpa. Photo: Pioneer Adventure