Alexandra David-Neel sought freedom from convention, and preferred sleeping in caves and traveling barefoot. In 1924, the Buddhist scholar, travel writer, explorer, and former opera singer crossed the Himalaya in winter to reach the sacred city Lhasa. She became the first European woman to do so.

Alexandra David-Neel wrote more than 30 books about her travels between 1911 and 1980.

David-Neel was born in Paris during the Victorian era. Remembered for its prudishness and conservative beliefs, the epoch determined a women’s role within society. When this ended in the early 1900s, opportunities for self-expression and innovation slowly presented themselves. But only for men. Women were expected to marry and run a household. This did not appeal to David-Neel.

She desired unpredictability and insisted on creating her own rules. A strong sense of freedom led her to run away from home when she was only five years old. It was a characteristic she repeated during her lifetime.

A young but ever-flamboyant Alexandra David-Neel.

Spiritual beginnings

In adolescence, she found her calling. Literature awakened her to Eastern beliefs, and she became a devotee of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society.

Founded in 1875, the Theosophical Society sought to bridge the culture between East and West by emphasizing the commonality among humans. Different religions, it argued, are simply unique expressions of truth.

Enthralled by the idea of a simple lifestyle, she was led to Eastern philosophies, especially Buddhism and the self-restraint of the Eightfold Path. When she was 15, she also began studying music as a means to conform. By the time a tutor noticed her natural singing talent, she was already uncomfortable with the confines of her era and gender. Her second runaway followed: One day, she set out for a hike and continued through the Alps to Italy. Her frantic mother retrieved her from Milan.

The restless David-Neel spent the next few years trying to appease her mother by taking jobs more customary to women. In 1891, a sizeable inheritance offered her the first opportunity to live as she pleased.

She spent a year traveling through Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and India. When she returned, she wrote her first book. Published privately, it failed to win an audience.

Opera singer in Asia

Her home in Brussels didn’t connect with her beliefs. Desperate to leave, she took an opera-singing position in Hanoi. Starring under the name Alexandra Myrial, she was a sensation. Her unique ability to connect with the feelings of her characters propelled her career. She sang opera through Indochina and Europe until her voice began to falter.

There was nothing more interesting to David-Neel than travel. Opera singing had invited her to experience other cultures, and she craved more. Deeply involved in the beliefs of Buddhism and the Greek stoic philosopher Epictetus, she wanted to explore their origins.

Marriage of convenience

In 1900, she wed Philip Neel. He was a wealthy rail engineer who needed a wife for respectability. She needed money to travel. There was little love between them.

The relationship was strained for David-Neel, in particular. She tried to live the life her husband needed. Eventually, she asked him to let her travel alone. He agreed. She left in 1911 and didn’t see her husband for the next 14 years.

At first, David-Neel returned to India. She stayed in monasteries and zigzagged across the country. When she met the Dalai Lama in 1912, he suggested that she learn his native language, Tibetan. Studying this ancient language fit effortlessly into her spiritual practices.

In a Sikkim monastery, she met a 15-year-old monk, Aphur. Their spiritual connection was instantaneous and she adopted him as her son. Aphur became David-Neel’s lifelong travel companion. Their first trip was north, into the Himalaya.

In a cave for three years

On the border of Tibet, at 4,000m, the two lived in a cave between 1914-1917. They braved freezing temperatures and scrounged for food. They spent most of their time meditating. Twice, they attempted to infiltrate the forbidden city of Lhasa in disguise.

Tibet was a common beacon for foreigners. But the country was strictly closed. David-Neel and Aphur entered illegally and were swiftly expelled.

With World War I at Europe’s doorstep, the pair set off in the opposite direction, first to Japan, then onward to Korea and China. For two years, they translated Tibetan books, living as monks in China’s Kumbum Monastery.

But again, David-Neel was restless. She struggled to stay in one place for long, and Tibet beckoned. She and Aphur set off again to attempt to enter Lhasa. This time, they succeeded.

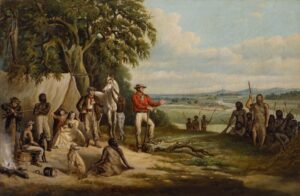

Alexandra David-Neel became the first European woman to enter Lhasa.

Pilgrims in disguise

The mature David-Neel, by now an inveterate traveler.

First traveling through the harsh Gobi Desert, then through China, the pair battled the elements. They navigated mountain paths and flooded roads, walked through jungles, and endured harsh Chinese winters. They ate whatever they could, and when there was nothing, they boiled the leather from their shoes. In 1924, they entered Lhasa their holy grail, disguised as pilgrims.

This time, they visited the Potala, the Dalai Lama’s winter residence. But their trip was cut short when David-Neel blew their ruse while taking a holy bath.

Before they could be apprehended, the penniless pair fled to Gyantse to enlist the help of a British trade agent stationed there. By now, David-Neel was a famous French explorer. However, some people assumed that she was a spy sent by the French government. With the aid of the British agent, they sneaked back to France.

Meets husband again after 14 years

It was 1925, 14 years since she’d first set out, when David-Neel showed up at her husband’s door with an adopted son. The couple separated, and David-Neel began work on her book, My Journey into Lhasa. She bought a home in Provence for her and Aphur. Here, she wrote many of her books. In 1937, her relentless legs again got the better of her. This time, she headed to China.

On the cusp of the Sino-Japanese war, David-Neel and Aphur ventured through Japan, China, and India. They witnessed the brutality imposed upon civilians unwittingly caught in the conflict. They maintained their spiritual disposition, unwavering from beliefs that seemed removed from the hostility around them. When David-Neel’s husband died in 1941, she had to return home to settle his estate. Because of World War II, it took five years for her to return to France. She arrived back in 1946.

Back in France

David-Neel’s reputation was primarily centred around her persona as a traveler and explorer. But David-Neel’s poor temper often took precedence. She quickly lost patience with those who didn’t live up to her spiritual expectations. Buddhism and teachings of the East had become more commonly practiced, and she only welcomed those paying homage to her as the author of books from which they had learned.

Together David-Neel and Aphur lived a quaint European life. But it wasn’t easy for them. Aphur indulged his unhappiness inside cafés, smoking and drinking. In 1955, he died of uremia.

David-Neel was grief-stricken. She and her adopted son were kindred spirits who had shared experiences that few people related with. She became reclusive and bitter. Housekeepers stayed only for short periods. David-Neel’s temper drove them away.

In 1959, Marie-Madeleine Peyronnet became more than a housekeeper. She stayed long enough to support David-Neel like a member of her own family, nursing her until her death.

Final years

David-Neel’s final years were unhappy. She preferred living a nomadic life in the mountains, not settling in one place as an old woman. Shortly before her 101st birthday, she died.

Behind David-Neel’s unhappiness and agitation was a woman who adored the simplicity of Eastern philosophy. She was happiest searching for food instead of buying it in a store and preferred sleeping on hard wood to a soft mattress. Those monks who devoted their lives to something greater than commercial enterprise were her spiritual guides.

In turn, she inspired spiritual leaders Ram Dass and Alan Watts, and poets Jack Kerouac and Allan Ginsberg. In travel, she proved that one can easily overcome the lack of daily comforts when the mind is connected spiritually. She published more than 30 books.