Did you ever wonder how Britain separated from the rest of Europe? Long before the crazy geopolitical mess called Brexit, an area rich in resources connected the two landmasses.

However, after a period of geological change, long ice ages and other natural disasters, Doggerland vanished beneath the waves of the dreadful North Sea, causing the separation of Britain from the continent. Now, scientists believe they finally know what happened to this Northern European Atlantis.

An ancient plain

In the 1990s, a professor from the University of Exeter named Bryony Coles coined the name Doggerland after Dogger Bank, a large sandbank in the middle of the North Sea. The word “dogger” refers to a type of medieval Dutch fishing boat specific to the area.

This extensive landmass stretched from Britain to the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Scandinavia. Doggerland covered approximately 46,620 sq km and occupied what is now the North Sea and the English Channel. Most importantly, it connected the British Isles to mainland Europe. It included vast wetlands, rivers, lakes, and marshes in which dwelt woolly mammoths, saber-toothed cats, hyenas, and other ancient species.

These animals provided valuable food sources for the Neanderthal population. Because of its abundant resources, flamboyant researcher Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof (aka the Overdressed Archaeologist) calls Doggerland the “heart of Europe.” Droves of hunter-gatherers came here, following the herds.

Ancient forest buried in the sand in Northumberland. Photo: Dave Head/Shutterstock

“Doggerland was one of the most attractive and important areas for human settlement in northwestern Europe in the Last Pleistocene/Early Holocene,” states another researcher, James Walker.

Accidental discovery

No one knew of Doggerland’s existence until 1931. By chance, a fishing vessel called the Colinda extracted a hunk of stinky peat just off the coast of Norfolk. On closer examination, the peat contained a Mesolithic barbed harpoon made from an antler measuring 21.5cm long. This harpoon dated back to 10,000 BC. While it does not seem like much, this find heavily suggested that more prehistoric secrets lay at the bottom of the North Sea. And they did.

The end of the last ice age changed everything for Doggerland. Around 12,000 BC, as temperatures increased, melting glaciers caused sea levels to rise. Over time, Doggerland started to vanish into the sea. By around 7,000 years ago, it had almost completely submerged, except for a sliver of sandbank known as Dogger Bank.

Britain then became the solitary island it is today. The only question remaining is how Doggerland vanished. Was it a gradual process or did something more sudden and dramatic sweep it below the waves?

The search

More pieces of evidence have turned up over the years. Amateur archaeologists and scientists greatly fueled the Doggerland search, combing the beaches for artifacts and clues. A Facebook group called Doggerlanders invites people to share their knowledge and discoveries. Some have even posted pictures of supposed well-preserved footprints of Neanderthals.

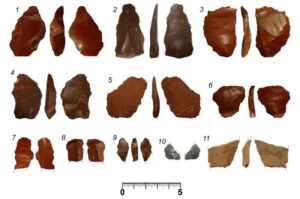

Some searchers have successfully uncovered artifacts that wouldn’t have otherwise been found. In 2009, a 40,000-year-old piece of a skull turned up off the coast of Zeeland. In 2016, a nurse named Willy van Wingerden discovered a 50,000-year-old artifact made of flint, minor human remains, and hyena bones along a beach in Rotterdam.

Ironically, much of the Doggerland data came, not from funded expeditions, but rather oil and wind farm companies. They helped map and gather evidence.

Exhibition in the Netherlands on Doggerland. Photo: Photo: Shutterstock

As of today, there are over 2,000 objects recovered from Doggerland. These include human remains, animal bones, axes, hammers, and fossils. The public was able to view many of these in a 2021 exhibition in the Netherlands titled Doggerland: Lost World in the North Sea.

Link to Atlantis?

A popular theory attributes Doggerland’s fate to a sudden catastrophe. Catastrophism is the hypothesis that Earth’s formation comes from a succession of fast, violent natural events. Such events include the Theia Impact theory, the Great Deluge from the Bible and other cultures, and stories in which mega-tsunamis wiped out entire populations.

Eccentric Frenchman and engineer Jean Deruelle spent decades trying to prove that Doggerland was in fact Atlantis. We all know the story, originally cited by Plato, of an idyllic city state swamped overnight. Undoubtedly, the similarities between Doggerland’s fate and that of Atlantis made Deruelle try to connect the dots. His magnum opus, L’Atlantide des Mégalithes, explored the links between the two. He believed that Plato’s Atlantis was a “great plain” rather than an island.

According to political scientist and catastrophist Alfred de Grazia (1919-2014), Druelle believed that Doggerland matched the classical Atlantis description of a great plain. He stated that Atlantis even contained a dike to keep the North Sea at bay — a preventive barrier that was ultimately unsuccessful. He also described Atlantis as rectangular in shape.

While his notions are worth considering, several holes in his theory stand out. His date estimate of the catastrophe, for one thing, between 7,000 BC and 2,600 BC, is later than what scientists have come to agree on.

Two theories

Of the two leading theories, the first suggests that a powerful mega-tsunami destroyed Doggerland and cut off Britain from the mainland. Coincidentally, 8,000 years ago, a major underwater landslide off Norway triggered a tsunami in the North Sea. They call this the Storegga Slide. Some archaeologists extracted cores of soil which held bits of broken shells and DNA from ancient trees which point to the tsunami theory. Additionally, analysis of hunter-gatherer remains indicate a decline in the local population around that time.

Yet computer models suggest that the resulting wave was not big or threatening enough for such a permanent change. Even if such a wave came, the waters soon went back to normal levels.

Most favor a gradual rise in sea levels after glaciers and ice sheets began to melt. Ice covered all of Scandinavia and Scotland. National Geographic suggested that due to the slow rise, people had to abandon the once prosperous hunting plains down below in favor of higher ground.

Conclusion

Most likely, Doggerland suffered from a gradual rise in sea levels which submerged the continent in the North Sea. It is very rare for a tsunami to change a landscape by itself. If a giant wave did have something to do with its disappearance, then it could have been a starting event, which then led to a period of higher sea levels as the glaciers continued to melt.