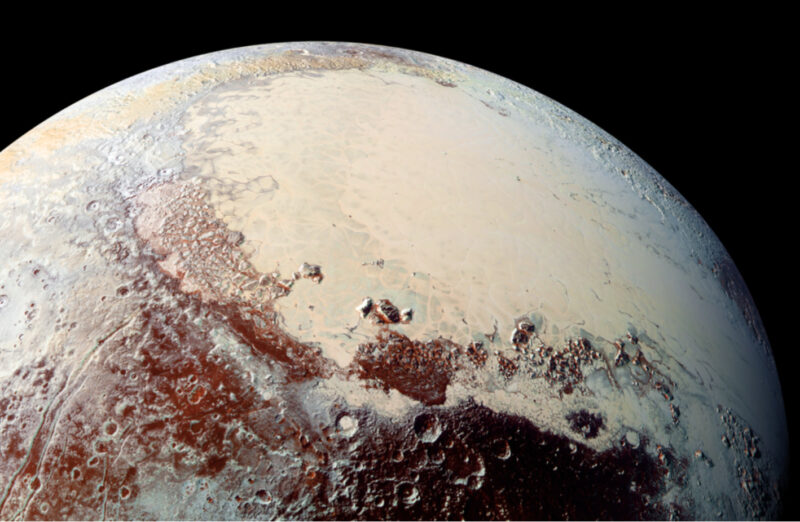

Pluto’s most recognizable feature is the giant, heart-shaped area in its southern hemisphere. NASA’s New Horizons mission camera only photographed this Valentine shape in 2015. Where it came from and how it formed has been a mystery — until now.

The Tombaugh Regio, the heart’s formal name, has baffled astrophysicists because of its shape, geology, and elevation. But a new hypothesis suggests that at least part of the heart came from a “splat” — a collision with another planetary body.

Researchers think that an object about 700km wide smashed at a low angle into the side of the dwarf planet, forming Sputnik Planitia — the western side of the heart. The object, made of 15% rock, struck at a 30-degree angle and created a bright, teardrop-shaped crater. Simulations show that the cataclysmic collision would have displaced Pluto’s primordial mantle. This contradicts previous ideas that the little planet has a subsurface ocean.

A high-resolution image of Pluto’s heart, captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. Photo: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

A window into early Pluto

Sputnik Planitia is approximately 1,600km wide and sits at a lower elevation than the rest of Pluto’s surface. “The formation of Sputnik Planitia provides a critical window into the earliest periods of Pluto’s history,” said Adeene Denton, co-author of the paper. She added that this discovery completely changed the story of Pluto’s evolution.

Harry Ballantyne, the study lead, explained how the impact created the iconic heart shape.

“Pluto’s core is so cold that the rocks remained very hard and did not melt despite the heat of the impact. Thanks to the angle of impact and the low velocity, the…impactor did not sink into Pluto’s core, but remained intact as a splat on it.”

The force of the impact created the drop in elevation, so the area sits around four kilometers lower than the rest of the surface.

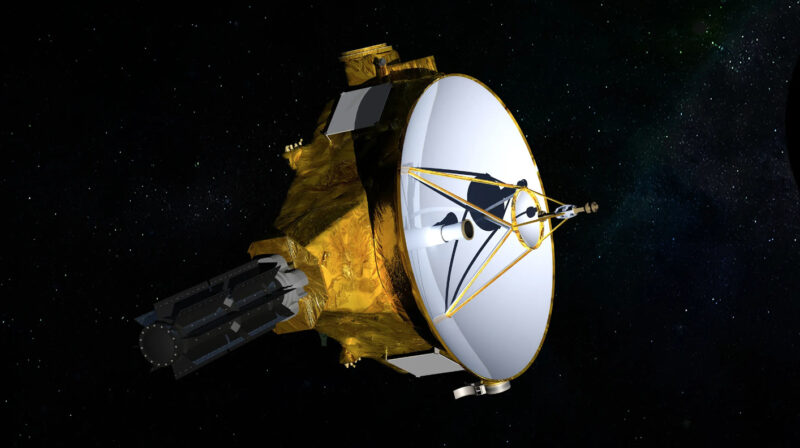

An artist’s impression of the New Horizon’s spacecraft. Image: NASA

Another notable feature of the heart is that it reflects far more light than its surroundings. Again, the researchers have an explanation — white nitrogen ice mostly fills the depression. Most of Pluto’s surface is darker methane ice.

“This nitrogen most likely accumulated quickly after the impact, due to the lower altitude,” said Ballantyne.

The New Horizons Mission, launched in 2006, is the first spacecraft to explore Pluto close up. It took nine years to reach the dwarf planet and a few more years to go to the Kuiper Belt, a vast ring of icy bodies at the outer edge of the solar system.

In 2023, NASA announced they will extend the mission until the spacecraft exits the Kuiper Belt in 2028 or 2029.