A 50-million-year-old fish is baffling scientists, who have no idea where it sits on the evolutionary tree. It doesn’t match up with any known relative.

The Pegasus Volans was discovered in the 18th century and has been somewhat of a mystery ever since. Scientists have made many suggestions about which species it may be related to. None of the theories has ever been convincing. Indeed, a new study suggests that all the theories are wrong.

‘I don’t know what the guy was thinking’

Its discoverer, Giovanni Serafino Volta of Italy, named the fish Pegasus Volans because he thought it was a larval form of the seamoth, Pegasus volitans. Paeleontologist Donald Davesne told Science News that this was nonsense. “They have nothing in common,” he said. “I don’t know what the guy was thinking.”

Others suggested it falls into the same order that oarfish and ribbonfish belong to, the Lampriformes. The new research seems to do away with all these ideas. Most of the guesses seemed to show what the fish isn’t rather than what it is.

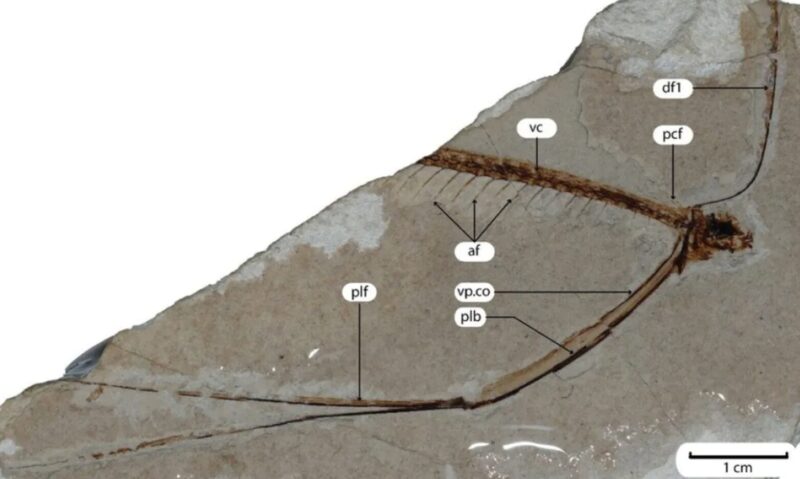

Davesne and his colleague studied two 50-million-year-old Pegasus Volans fossils from northern Italy, currently in museums in Italy and Paris. Both specimens are incredibly similar — same size, same ribbonlike bodies and large skulls. Photos taken under UV light and analyzed with a stereomicroscope ruled out its connection to oarfish because of fundamentally different skeletal anatomy and fins.

Pegasus volans fossil. Photo: D. Davesne

Davesne and Giogio Carnevale think the fish are likely related to cusk-eel larvae and fish larvae from the Teleostei group. The fish had very small abdomens, and their guts may have hung in pouches on the outside of the body. Teleost larvae also have this feature. However, the fossils don’t seem to be larvae themselves.

Part of the problem identifying them is that both fossils only show the front of the fish. The back end might reveal whether the fossils are adults or juveniles or how the fish lived.

The fish likely had very long fins for one of three reasons. First, to camouflage, second, to lure prey, and third, as part of its sensory system.

The fish’s uniqueness is clear enough that Davesne has chosen a new genus name for it. This will become public after the research paper is peer-reviewed and published.