Archaeologists have long known that humans and Neanderthals interbred, but where this took place has been hard to pinpoint. A new study may have solved the mystery.

More than just co-existence

Neanderthals and ancient humans co-existed for tens of thousands of years. It is no great surprise that they came into contact with each other. But in 2010, it became clear that they had done far more than simply cross paths. Researchers sequenced the Neanderthal genome for the first time, and it was apparent that some inter-species canoodling had occurred.

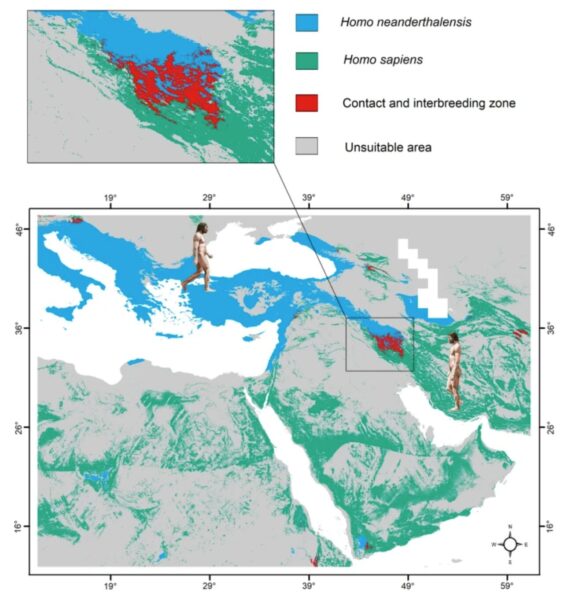

We know that interbreeding took place during the Late Pleistocene era. Using ecological niche modeling, researchers mapped the distribution of both groups in Southwest Asia and Southeast Europe during this period. They wanted to see where the two species overlapped.

This identified a potential meeting point, the Zagros Mountains, which stretch across modern-day Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Researchers believe that the mountains acted as a corridor between the Palearctic region that played host to Neanderthals, and the Afrotropical region that our ancestors came from.

The potential contact and interbreeding zones for the two Homo species in Southwest Asia and Southeast Europe. Image: Guran et al., 2024

Harsh climate may have forced interaction

The topography of the mountains and its diverse life meant that the area could support quite a large human population. The harsh climate of the time may have pushed both groups into small pockets in the region.

“The border areas of two realms…operate as refuges for species from glacial environments,” the team commented.

More importantly, the area aligns almost perfectly with the small amount of archaeological evidence we have. Remains from both groups occur throughout the mountains. The most famous of these sites, the Shanidar Cave in northern Iraq, has the best-preserved Neanderthal ever discovered.

Other studies found similarities between the facial features of Neanderthals and modern humans in the region, further supporting the hypothesis.

While ancient humans migrated out of Africa and traveled north across the mountain corridor, scientists know that Neanderthals were living on the Persian plateau. The research team has a single tooth and several tools that place them there.

This all ties in with the second wave of interbreeding that we know happened between 80 and 120 thousand years ago. The hook-up is still visible in our genetics.