At the end of September, a Polish party called off their attempt on a beautiful, forgotten gem: 6,990m Sang-E-Marmar, located in Pakistan’s Batura Muztagh.

Over two weeks, Damian Bielecki, Marco Schwidergall, and Lukasz Muller tried to make the second ascent of this marble peak via a new line in alpine-style.

”To get at it the way we wanted, we needed good acclimatization, a safe descent route, good route conditions, and…weather,” recalls Bielecki.

Unfortunately, at 5,500m, a dangerous serac blocked the route, and they felt compelled to retreat.

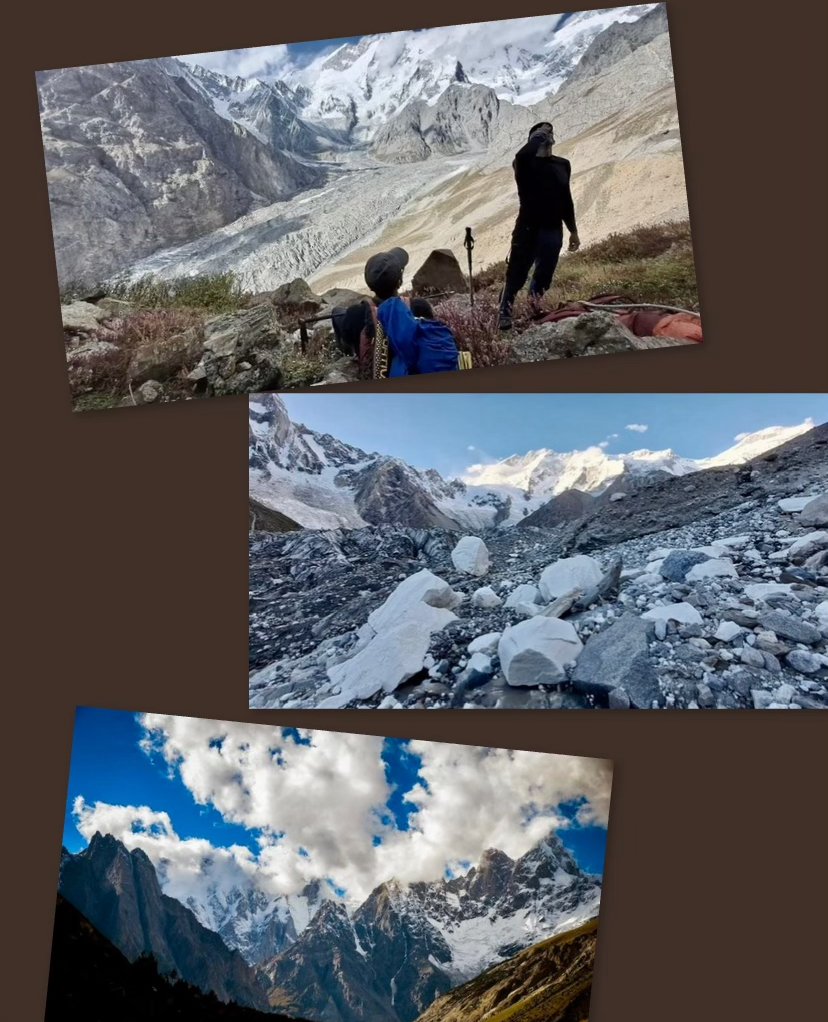

Photos taken on the recent attempt on Sang-E-Marmar. Photo source: Damian Bielecki

Although they failed in their objective, they came home with some options for a future ascent.

Let’s consider the thin climbing history of this nearly forgotten mountain.

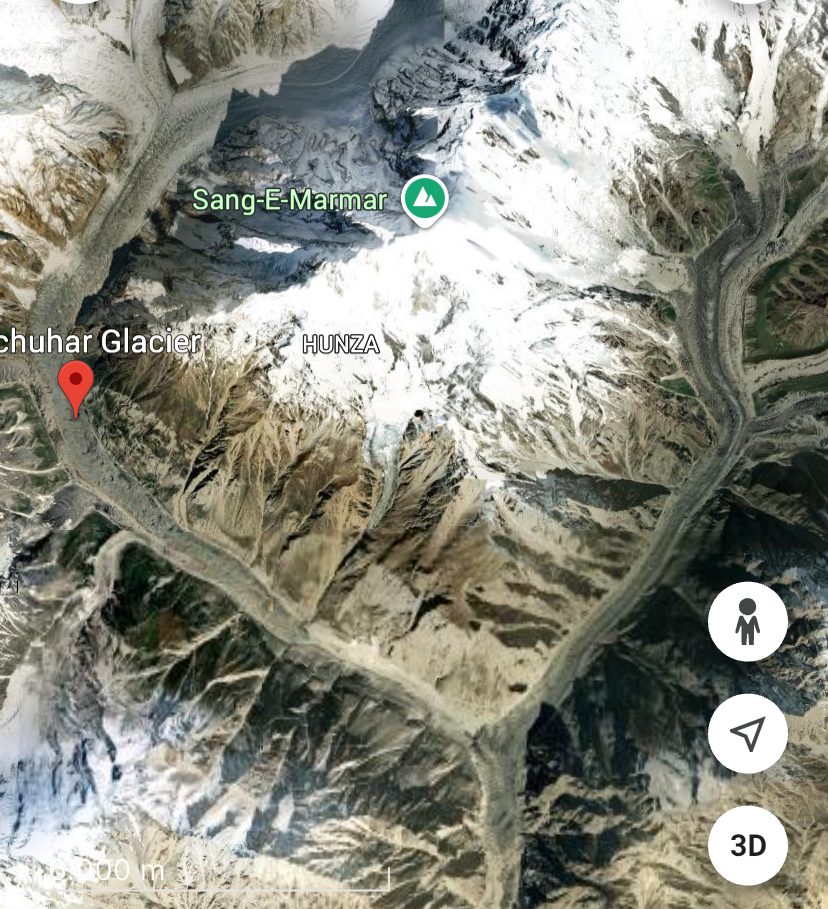

Sang-E-Marmar is a pyramidal peak in the Batura Muztagh subrange of the Karakoram, between the Muchuhar Glacier in the west and the Shishper Glacier in the east.

At 6,990m, Sang-E-Marmar is the fourth highest 6,000er in the world, after 6,995m Kohe Tez, 6,993m Machhapuchhare, and 6,992m Rishi Pahar, according to 8000ers.com.

Sang-E-Marmar lies between the Muchuhar Glacier, left, and the Shishper Glacier, right. Image: Google Earth

The first attempt

A Canadian expedition led by Ernest Frederick Roots first attempted Sang-E-Marmar in the spring of 1964. According to the American Alpine Journal, the Canadians arrived in Hunza in May 1964 to investigate the region south of Batura. They planned to locate and climb a peak known as Hachindar Chhish, which earlier expeditions had not visited.

The Canadians reconnoitered Hachindar Chhish from three sides of the massif but concluded that there was no safe way to reach the mountain.

Their attention then turned to ”a pyramidal massif of about 6,949m”, which the party called Sangemarmur (written with “u”). It means ”marble” and refers to a conspicuous band of yellow marbling across the summit. The Canadians established seven camps on the southwest face of what we now spell as Sang-E-Marmar. In the end, they had to retreat without summiting because of bad weather and high avalanche risk.

Sang-E-Marmar. Photo: theworldmountain.blogspot.com

The first ascent

Twenty years later, in 1984, Osaka University organized an expedition to Sang-E-Marmar. The Japanese team included Takashi Matsuo (leader), Akira Noguchi, Hiromi Okuyama, Takehiko Hirota, Tokio Kozuki, Masaya Oishi, Toru Sakakibara, Kenya Sato, Sibichi Miyata, Tomoyoshi Mizukava, and Hiroyuki Onishi. Their chosen line went up the southwest ridge.

To reach Camp 1 at 5,100m, they climbed 40º to 50º ice. The southwest ridge features two foresummits. They established Camp 2 at 5,800m, at the foot of the first foresummit.

At 6,400m, the Japanese set up their Camp 3. On July 11, six men left Camp 3, traversed around the second foresummit on the Batura side of Sang-E-Marmar, and finally reached the top. Two days later, the remaining members also topped out.

They fixed 3,000m of rope during the ascent. Although their successful line followed the most logical route, the southwest side was very challenging, highly technical, and dangerous. Theirs remains the only successful ascent of this peak.

Sang-E-Marmar. Photo: Rizwan Saddique

Before the recent Polish attempt, one other party had tried to scoop a second ascent. In the summer of 1986, a Belgian expedition led by Jacques Collaer tried the southwest face. The technical difficulty of the route, bad snow conditions, and falling rock prevented them from summiting. One climber came away with broken ribs because of rockfall.

The altitude controversy

The Belgians indicated in their report to the American Alpine Journal that the height of Sang-E-Marmar was 7,050m. This differs from the three other expeditions’ consensus height — 6,949m. However, neither of these heights are correct.

In 1964, the Japanese cited its height as “approximately 6,949m.” Several later sources, including the Belgians, called it 7,050m, so for a time, it was considered a 7,000’er.

However, according to Eberhard Jurgalski of 8000ers.com, the correct height is 6,990m.

Moments from the recent Polish expedition. Photo source: Damian Bielecki