In his seminal work of popular geology called Basin and Range, John McPhee first pinned the concept of deep time down on paper. Once we move past the history of recognizable humanity, from the first agricultural settlements in Anatolia to high-speed trains, our brains cease to comprehend the duration of events.

“Numbers do not seem to work well with regard to deep time,” writes McPhee. “Any number above a couple of thousand years — fifty thousand, fifty million — will with nearly equal effect awe the imagination.”

Describing a similar effect with regard to distance, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams writes more prosaically: “Space is big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space.”

So, with the goal of making human life look like peanuts, let’s examine the best predictions from geologists and astrobiologists for the next two billion years on Earth.

The Mediterranean, 2,000 years from now

Dark water laps at the side of a boat. What the boat looks like is impossible to say, but its sole passenger, lost in the Mediterranean after a terrible storm, steers it onward over the now-still water. Overhead, the North Star guides the sailor along.

Except in the year 4024, the North Star is not Polaris but Errai in the constellation Cepheus.

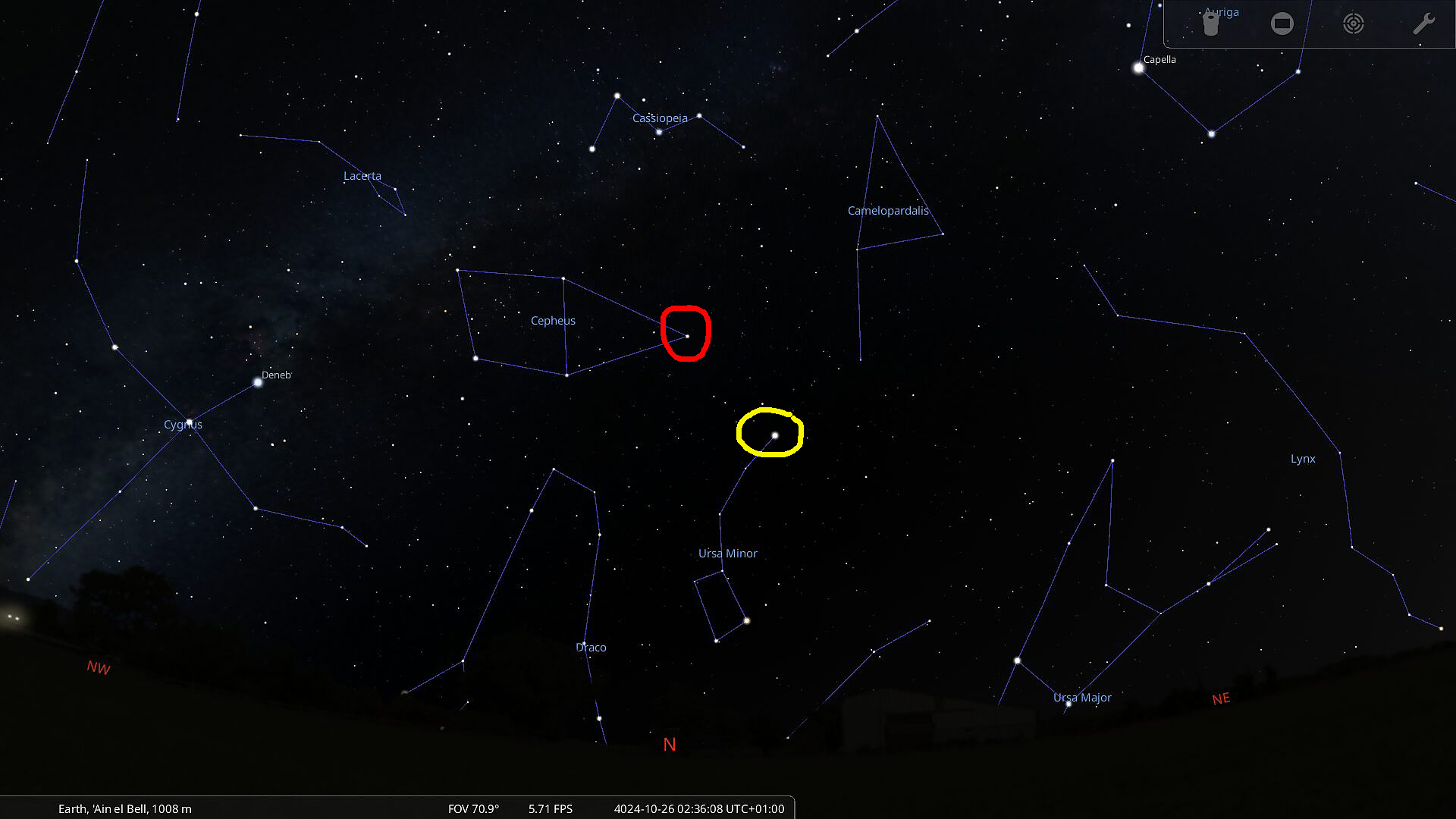

A view of the sky from the Mediterranean in the year 4024. Errai is the rightmost star in Cepheus, red circle. Our current North Star, Polaris, is circled in yellow. Photo: Stellarium

In the antiquity of 2024, Polaris was the North Star. You could run a string from it straight through the Earth’s axis of rotation. Even as the heavens appeared to turn throughout the night as the Earth spun, Polaris stayed where it was.

That time is gone. The slight wobble of the Earth’s axis has now brought Errai, a fainter star also known as Gamma Cephei, into the spotlight.

But although they’ve shifted slightly, the constellations that shine down look nearly identical to those of 2024. Cepheus, the king of Aethiopia in Greek mythology, sits astride his throne while his wife Cassiopeia looks on. The environment and inhabitants of the Earth of 4024 might be impossible to describe, but the sky above and rock beneath have barely changed at all.

The boat and its passenger drift onward, guided by Errai. The clock turns.

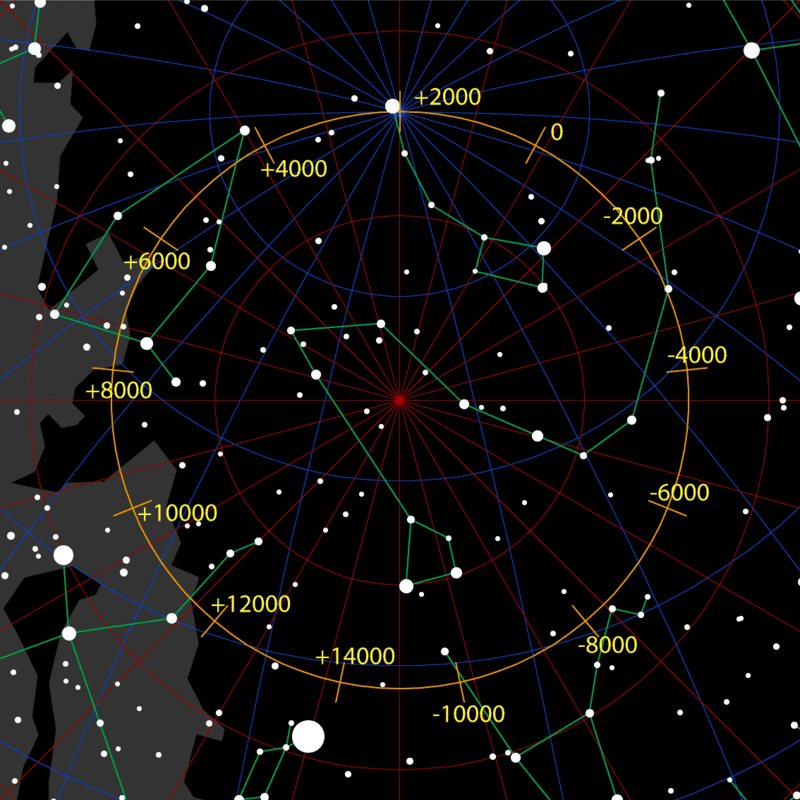

The precession of the North Pole through key stars. Polaris lies at the +2000 location and Errai at +4000. The largest star in the image, at +14000 years, is Vega. Photo: Tauʻolunga/Wikimedia Commons/additional labels by the author

The Sahara, 15,000 years from now

The brightest star in the summer sky has replaced Errai at the North Pole. Vega shines down on a Saharan climate of grassland dotted with shrubs, where herds of buffalo graze and splash in the shallows of massive lakes.

That same axial wobble that has brought Vega into the place of the North Star has altered the course of the seasons. Back in the 21st century, the Earth passed closest to the Sun during summer in the southern hemisphere, roasting the southern tropics. Summers and winters varied more in the north, but summers were milder than in the south.

Now the tables have turned. Summers expose the northern hemisphere to the Earth’s most intense radiation. Monsoons off the Atlantic Ocean course toward the hotter regions of North Africa, drenching what used to be a desert and transforming it into a landscape where life thrives. If there are humans, they enjoy swimming in its rivers. Perhaps they record the scene with a visual technology we cannot yet fathom.

Maybe someone paints the swimmers on a rock. That’s what humans did in the Neolithic, and left a record of a Green Sahara that endured long after the lakes had evaporated and the grass had withered away.

Neolithic swimmers at the Cave of Swimmers in Wadi Sura. Photo: Roland Unger/Wikimedia Commons

Hawaii, 50,000 years from now

The brand new island of Kama’ehuakanaloa steams in the morning sun. Lava courses down its flanks, spitting and frothing as the land finally stands free of the ocean.

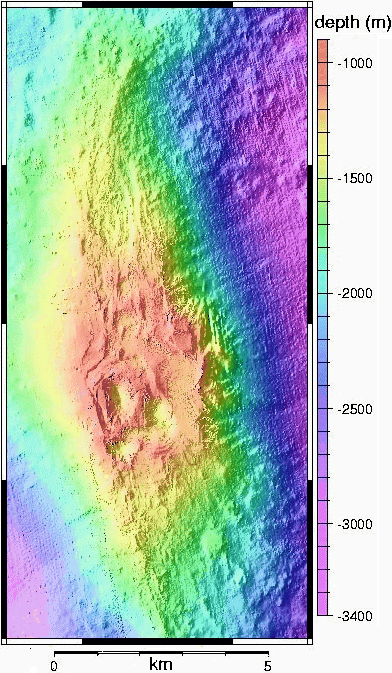

In 2024, the top of Kama’ehuakanaloa sat 3,000m below the ocean’s surface, occasionally lurching into seismic action with flurries of earthquakes. Thanks to a growth rate of 15cm every year — 15 times as fast as the Himalaya — in 50024 CE, it has claimed its place as the latest Hawaiian island.

Computer reconstructions from seismic data allow us to see the shape of Kama’ehuakanaloa, even though it sits in darkness below the ocean’s surface. Photo: University of Hawaii

Kama’ehuakanaloa might seem inhospitably volcanic, but pioneer species already call it home. Lichen, a symbiotic organism comprised of a fungus inhabited by algae or cyanobacteria, has crept over from the older, more established Hawaiian islands. Soon, crickets will take up residence on the new volcanic rock, subsisting off nutrients blown in on the salty sea wind. Ferns will follow, and then trees.

The floodgates open, and life rushes in.

Himalaya, 20 million years from now

The land once known as Nepal is gone. It is not merely that the nation has long since been lost to history, along with every other nation from the 21st century. Rather, the Indian subcontinent has crushed all the land that used to make up Nepal, subducting some under itself and pushing the rest up against Tibet.

Rockfall clatters down the slopes of what remains the world’s highest mountain range. While the theoretical maximum height that a mountain with a typical base size can sustain is 45km, rockfall keeps the practical limit far beneath that. Still, the summit of Nanga Parbat, now the world’s tallest mountain, juts thousands or perhaps tens of thousands of meters into the Death Zone. It dwarfs Makalu, the second-highest peak.

In 2024, Nanga Parbat sat at the position of ninth tallest mountain in the world. But a network of new rivers at its base eroded much of the landscape, allowing the rest of the rock to float higher on the mantle. Nanga Parbat climbed upwards at a steady rate of 7mm a year, over three times faster than Everest. According to simulations, another modified river system centered on Makalu will likely make it the world’s second-tallest mountain.

Now, ice blankets everything above the tree line. In the stillness of the mountains, nothing lives. If humans are here, and if they climb mountains, they have no choice but to spend the entire climb on supplemental oxygen. Seracs collapse in omnipresent icefalls, avalanches shred the slopes, and rocks plummet downward as the foundations of each mountain fail to support its height. Any climber who makes it past these objective hazards to stand at the summit will be outfitted more like an astronaut than a 21st-century alpinist.

Perhaps humans still exist, and one makes it to the top of Makalu. As their breath whistles through their mask, they gaze westward over the land where Nepal used to be. Gone are Rolwaling Valley, Namche Bazaar, and Kathmandu. All have been crushed against the flanks of the Himalaya.

Twenty million years from now, Makalu will probably be the world’s second-highest peak. Photo: Sebastian Alvaro

Eurafrica, 50 million years from now

Erosion is dragging down the Himalaya, but a new mega-range has taken its place. Forty million years ago, the northwestern Nubian plate split off from the eastern Somali plate, ripping Africa in two and causing the Red Sea to flood the land in between. Now Nubia has finally completed its journey across the Mediterranean, forcing water into the Atlantic and closing the gap with Europe. Italy, Greece, and southern France have buckled up into the air, rocketing the Alps as high as the Himalaya used to be.

A rift along the boundary between the Nubian and Somali plates. Photo: Thomas Mukoya

The inhabitants of Eurafrica live beside an enlarged Atlantic Ocean, big enough to gather storms of the same force as the Pacific. Monsoons slam into the coast every wet season, shredding the forests that now cover what used to be regions of dry shrubland.

The mountains bloom.

Pangaea Proxima, 250 million years from now

The deserts at the center of the supercontinent broil in 60˚C winds.

A few reptiles lurk under the sand, but most of the world lies still. If any large animals live here, they most resemble the gorgons of the Permian: dinosaurish beasts with rat-like faces and large teeth. Even those tenacious creatures would depend on unpredictable seasonal flooding, with mudslides just as likely to bury them alive as bring them the water they need to live.

An artist’s illustration of the largest gorgon species, with a human for scale. Photo: Mario Lanzas/Wikimedia Commons

Life flourishes more along the northern and southern coasts, where the weather stays temperate year-round. But this is a world that has long forgotten the concept of glaciers. We have returned to a global greenhouse, where even the poles never drop below freezing. In the last greenhouse period, tropical forests blanketed Antarctica.

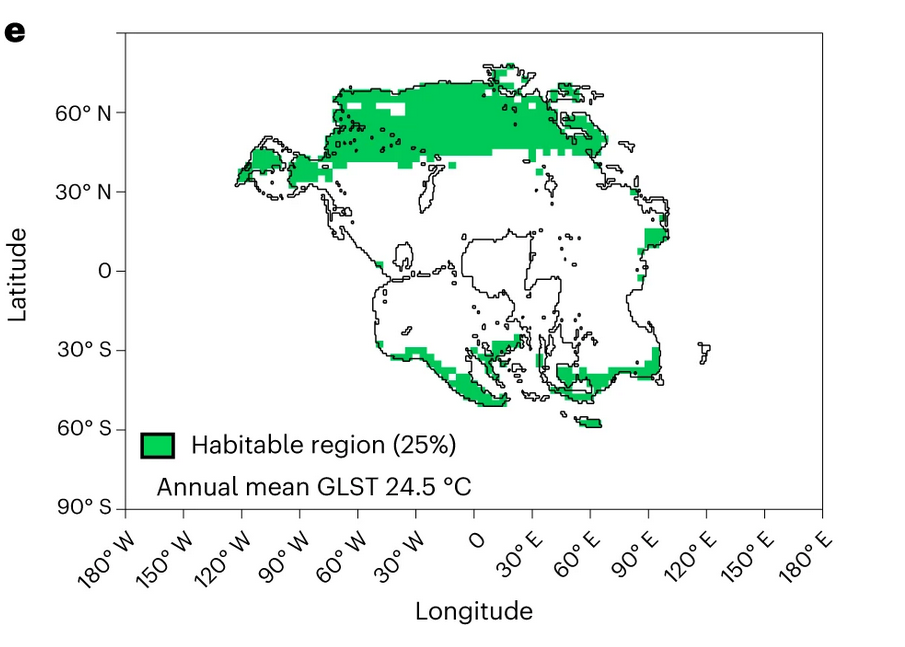

Now there’s no land at either pole. According to the most dominant prediction of what the Earth now looks like, all the continents have collided into a new Pangaea. Massive volcanic activity has increased the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere to such an extent that, at most, only 25% of the continent is inhabitable to mammals. In these milder coastal regions, lush forests dominate. If mammals still exist, this is where they live.

Back in the central desert, something like a gorgon comes across a dying pool of water and lives for another day. Or it doesn’t.

The most optimistic mammalian habitability predictions for Pangaea Proxima. Photo: Farnsworth et al 2023|Nature Geoscience

The dead forest, 500 million years from now

Being a tree is a cutthroat business. After the supercontinent of Pangaea Proxima ripped itself apart, ice rushed back into the world. Carbon dioxide levels dropped precipitously, starving plants. Only a few stragglers remain, the last of their kind.

Now grasses and shrubs dominate the arid land. The survivors process sunlight differently than trees, using a photosynthesis process called C4 that makes more efficient use of carbon dioxide. Without the leafy plants and trees that used to make up over 90% of flora, most large fauna have gone extinct.

Black saxaul, one of just a handful of C4-photosynthesis trees that could survive a global drop in CO2. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

It’s not just the carbon dioxide drop that has picked off species. The Sun shines brighter than ever as it edges toward leaving the Main Sequence, the period of time that describes the stable, long-term midlife of stars.

But even if the land is dying, the ocean still thrives. Seaweed drifts in the warm currents. Vertebrates and invertebrates scuttle over the seafloor. At the vents, sponge cities and bacteria reign supreme. Life is slowly returning to its origins.

The greenhouse, 1 billion years from now

The oceans are gone, and with them, plate tectonics and most multicellular life. Much of the water sank into the mantle, while the rest evaporated into the now-waterlogged atmosphere. Thick clouds blanket the world.

Despite the cloud cover, the temperature never drops below 45˚C. In its last sputters of middle age, the Sun radiates 10% more light than it did in the halcyon days of 2024. The Earth now resembles a heavily oxygenated, humid Venus.

The future Earth might look a lot more like this blurry photo of Venus than the Earth of today. Photo: Russian Academy of Sciences/Ted Stryk

Still, life endures. Simple photosynthesizers clog scattered lakes at the Poles, turning their surfaces the emerald green of cyanobacteria and the amethyst of sulfur algae. They paint this dying world in technicolor.

The Earth, 2 billion years from now

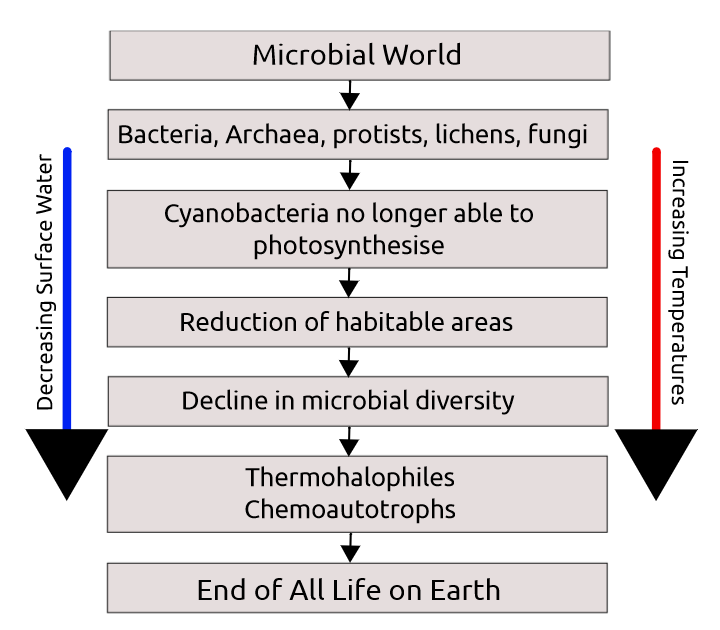

All the algae is long gone, all the cyanobacteria in their bright blue and green splashes. Photosynthesis has not been possible for hundreds of millions of years. Now only a few single-celled organisms remain, clustered in the scant pools of water that remain on what used to be living mountains and now are merely dead ridges on a stagnant landscape.

A diagram showing the last surviving life on Earth around two billion years from now. Photo: O’Malley-James et al 2012

The temperature is that of a furnace. In the sky above, barely any water vapor, oxygen, or carbon dioxide remains. Still, for the little organisms that subsist off carbon dioxide and chemical reactions in the heated rock itself, that’s enough.

But the temperature is increasing, and carbon dioxide is disappearing alongside the last liquid water. As it does, even the rock-eating chemoautotrophs are starving. It will take a long time for all of them to die off.

During the day, the Sun beats down. At night, the sky swarms with stars as the Andromeda Galaxy collides with the Milky Way. Nothing exists with eyes to see it, but it’s beautiful.

Another chemoautotroph dies.