One of the most remarkable climbs of the year took place earlier this fall in Pakistan’s Hindu Raj, close to the Afghan frontier. Yudai Suzuki, Kei Narita, and Yuu Nishida of Japan explored that wild, isolated place last year during their first ascent of Ghamubar Zom V. This year, they came back for more, and Suzuki summarized the expedition in a detailed, engaging report to ExplorersWeb.

In a nutshell, on September 23, the team completed the first ascent of the west face of 6,523m Thui II. The peak had only been climbed once, 46 years ago, from a different side. The story of this new Japanese climb, in the purest style and overcoming extreme difficulties, is simply epic.

The steepest, most seductive

“Last year, I stood on the summit of Ghamubar Zom V and could not forget the beautiful view of the sun setting over the mountains,” Suzuki recalls. “One of those peaks was Thui II, the steepest and most seductive.”

The team agreed then to go for that peak as soon as they could. But researching that obscure area was not easy. Thui II had been climbed only once before, back in 1978, 11 years after the first attempt by a British team in 1967.

The only information the Japanese could find about the west face and the approach to it over the Rishit Glacier came from a French team that had visited the place a few years ago.

But the French were there in spring, and the Japanese wanted to climb in September, as they had done on Ghamubar Zom V. Then they came across a short but fascinating note in The Himalayan Encyclopedia: “Thui II is the third highest peak in the range…and its triangular spire is said to be the most magnificent solitary peak in the Hindu Raj,” it promised alluringly.

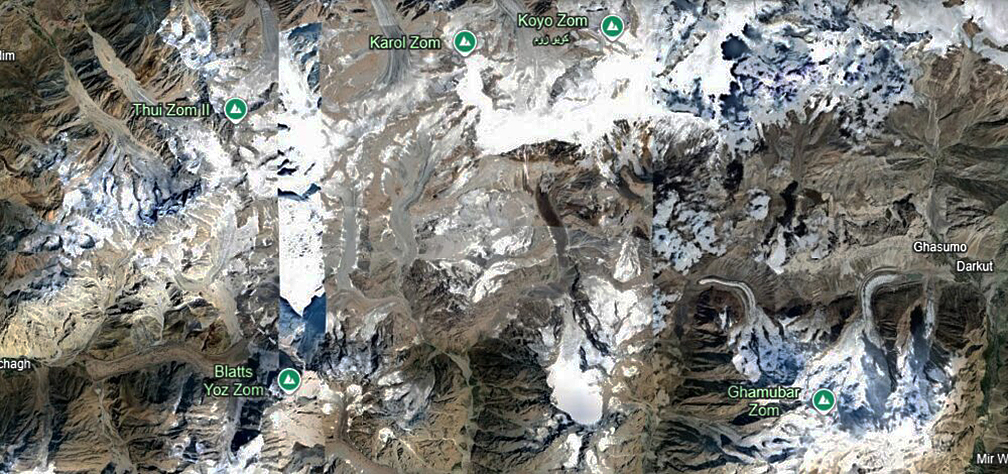

Peaks of the Hindu Raj, northern Pakistan, on Google Earth.

“From my research on Google Earth, the west wall of Thui II has ice and rock formations suitable for mixed climbing all the way to the summit,” said Suzuki. “It is in an unexplored area on the northwestern frontier of Pakistan, so it looks like it will be a long and adventurous climb.”

Just what they were looking for.

On the Afghan border

Arriving in Pakistan in September, the team drove north for two days from Chitral to a small village called Shost on the Afghan border. They continued up steep trails to a hamlet called Trikand, then walked for six to seven hours from Trikand to their base camp on a grassy plain at 4,300m.

After some days of rain, a long weather window opened, and the climbers headed to nearby Rishit Peak to acclimatize.

“It took about five days to reach 6,000m, and we were able to spend two nights at a col at 5,740m just north of Rishit Peak,” wrote Suzuki.

On the way, the climbers had a chance to study their targeted peak.

“Our planned route consisted of a lower snow slope and mostly nearly vertical ice and rock,” Suzuki noted. “The crux, in particular, seemed to be just below the summit at over 6,200m, so it looked like it would be an adventurous climb of nearly 1,500m.

They wanted to summit in a clean, single push, although some passages were not clear. But first, they had to wait out a week-long stormy spell.

“After the sun returned…we couldn’t see the condition of the snowfields above from base camp,” Suzuki recalled. “We were worried about avalanches, but we seized the good weather period, returned to ABC, and set off toward the mountain with four to five days of food and some gear.”

Unknown terrain

“From the base, we simul-climbed two long pitches at a good pace until we reached the point where the actual steep climbing began,” Suzuki said. “From the start, there was some suspicious melting ice.”

They completed the first part on a smooth mixed wall, looking for its weak spots, with the melting ice showering on their heads.

“Fortunately, at 5,600m, there was a crack next to the ice, and we managed to climb up by dry tooling and jamming. It was an M7 pitch with snow and ice stuck in the crack.”

The crack was too wide for the Camalots they had brought, so they had to free-climb it. Then followed more difficult pitches, including sections on completely vertical rock and then on a layer of melting ice. Finally, a snow band offered just enough space for a bivouac.

“As the sun was about to set, we expanded the space of about two meters [by adding snow to a groundsheet] and made our first bivy at 5,810m, protected by a big boulder.”

Platform for the first bivouac at 5,810m. Photo: Kei Narita

“On the second day, we first ran up the snow band with about three pitches of simultaneous climbing,” Suzuki recalls. “Then we got into a steep mixed couloir, progressing fast on hard ice in the early hours of the morning.”

Yuu Nishida finds a weak point on the rock face. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

The team did seven 60m pitches and then “climbed a steep couloir with hanging belays along the way,” said Suzuki. “There was a vertical chimney section without ice or snow, but luckily it was very narrow, so we managed to climb it with our bare hands.”

Finally, they crawled up the fragile rock to a small ridge-like slanted area. Again, they extended the space for a third person on a second bivouac at 6,250m. By now, they had climbed about 25 pitches.

The second bivouac. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

The long summit day

On the third day, the team had only 300 vertical meters left. They considered leaving part of their gear at the bivy site and returning after they reached the summit, but the upper slopes looked difficult. They were also not sure how the day would unfold. In the end, it was good they took everything with them, as difficulties confronted them immediately.

Kei Narita on a beautiful mixed line that barely held together in the cold conditions of the morning. Photo: Suzuki Yudai

“On the first pitch, we did a nasty 10m down-climbing traverse,” said Suzuki. “On the second pitch, we climbed a thin layer of ice stuck to the concave parts, which was a truly mixed climbing pitch. There was very little protection, but we managed to insert a small Camalot on the side wall. I was climbing second, but it was probably M5+/M6.”

Finally, the climbers had to decide how to approach the last and most technical pitches.

The finale

Suzuki’s account of those upper pitches deserves to be quoted in full:

We could go left or right, but if we went left, the route would just turn into a couloir and become boring, so we decided to consider the vertical [rock] wall on the right. At first glance, it looked impossible to climb, but miraculously, it was connected by hard and high-quality grabs, and the rock quality was excellent.

Nishida went up by dry tooling. We were already over 6,300m, and every vertical movement left me out of breath, and my head hurt. The fourth pitch was also an excellent mixed climb at an angle of about 80˚. It was unbelievable that the sections of the line were so well connected.

Kei Narita dry-tooling at 6,300m. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

On the fifth pitch, I took over the lead, but the wall had changed completely. Looking up, I saw a big slab covering the area. What should I do?

First, I climbed to the base of the slab and found a single, thin crack. I expected it would be difficult to make a big traverse from here, so I gambled and went straight up the crack. Although the sun was shining, it was still cold to climb with bare hands at 6,400m, but I couldn’t do it with gloves, so I climbed while jamming with bare hands.

When I had climbed about halfway, the footholds disappeared and I took off my crampons, but I couldn’t free-climb anymore, so I switched to aid-climbing. I decided on small Cams and Tri-cams, and slowly climbed with a few free moves where the crack was broken in places.

Eventually the crack completely broke, but I managed to mantle back, because I found a rock flake one meter away, where I placed a tiny piece of gear. It was quite doubtful whether we could go straight up from this point, so we decided to stop at the terrace.

On the sixth pitch, we could see fine flakes when we looked straight up, but we didn’t know what lay beyond that. We figured if we couldn’t see the top, it meant that the slope was flattening out and we could manage it.

Yudai Suzuki follows the hard rock flakes and connects his line to the final ice wall. Photo: Kei Narita

We climbed straight up about five meters using the grabs, and we could see the ice slope as far as the eye could see. This would connect us to the summit! As we moved from rock to ice, we immediately realized that this was blue ice. But we figured we should be able to reach the summit soon.

The climbing up to this point was more technical than we had imagined, and it was already past 3 pm. We pounded our axes into the hard ice with all our might — torture! — but we were at over 6,400m and couldn’t go fast, despite the late hour. We took turns climbing the last four pitches of ice.

As Nishida was climbing, the other side suddenly dropped off, and we jumped onto the summit. The sky was already deep orange, and we were exhausted by the 6,523m altitude and strong winds. We spent about an hour and a half preparing a summit bivouac.

Bivouac on the summit of Thui II. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

On the fourth day, when I woke up in the morning, Ghamubar Zom V, which I had climbed last year, towered majestically in front of me. From this angle, I could see the line from last year as clearly as if it were in my hands. It was moving to realize that I had climbed a longer ridge than I had imagined.

The descent

All that remained was to descend. This would take a whole day.

At 8 am, the wind was still strong and cold when the climbers started rappeling down. But Suzuki was “grateful” for the wind, as it blew away the heavy snow.

“I had thought of climbing down the ridge a little and descending on the Lisit Peak side, but the ridge still looked bad,” he noted. “I decided that it would be safe to rappel along the climbing route.

The climbers used V-threads whenever possible to rappel on the ice and rock, as they had just 25 meters of spare rope that they could abandon on the wall if needed.

“I drove two short pitons into the only place where there was nothing and rappeled all the rest from rocky outcrops,” wrote Suzuki. “After rappelling about 23 times from the summit, I finally reached the top of the first simultaneous climbing section. There, I left all 25m of rope and the four slings behind.”

Rappeling down. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

32 to 34 pitches

It was after 7 pm, already dark when the exhausted Japanese reached their bivy tent, which they had struggled to pitch in high winds and bitter cold.

“But the snow was firm, and there was no risk of anything falling from above,” Suzuki noted. Counting the simul-climb and the standard climbing, the line took 32 to 34 pitches.

A long descent followed on the next day down the same route. The climbers repeated the simul-climb sections when down-climbing.

“In places, we encountered black ice, which is unique to the Himalaya, but we calmly dealt with it while deciding on the screws and cams, and landed on the Risht Glacier at 10 pm,” Suzuki said.

In one more hour, the climbers had stumbled back to their Advanced Base Camp.

“We took off our harnesses for the first time in four days after 11 o’clock that night,” said Suzuki. “I was filled with an indescribable sense of fulfillment and slept peacefully in the thick air until 10 the next morning.”

Back home

Now back home, Suzuki considers the climb a combination of high-altitude, high-difficulty, and high-quality mixed climbing.

“We also rock climbed with our bare hands and tackled a headwall that got steeper as we climbed,” he says. “In addition to the severe aid-climbing, the final section was, as always, torturous blue ice; plus, the two bivouacs using snow hammocks and the miserable bivouac at the summit were also memorable.

“This climb made me realize once again how all-round, free, and wonderful alpine climbing is. Above all, I am happy that I was able to climb this beautiful and wild unclimbed wall in the remote border of Pakistan directly to the summit in a simple, beautiful, and satisfying style.”

Kei Narita tackles thin ice and moves up a crack during the first day of climbing. Photo: Yudai Suzuki

The team named the route The Spider’s Thread after the ice formations that spread like a spider’s thread on the huge rock wall — and the countless giant spiders they found at base camp! The proposed degree of difficulty is ED+, M7, A2 for the 1,450m route.