For centuries, a lost Mayan city was buried under dense jungle in southeastern Mexico. The massive site, named Valeriana after a nearby lagoon, covers over 16 square kilometers. With an estimated 6,764 man-made structures, only the Calakmul site, 100km away, rivals its size.

Despite the fact that it only lay a short hike from the town of Xpujil, the archaeological community was unaware of this ancient metropolis hiding in the neighborhood.

Tulane University PhD researcher Luke Auld-Thomas discovered it by chance. Digging around the internet, he found a laser survey completed by a Mexican environmental monitoring organization, “on something like page 16 of a Google search.”

No other archaeologist seen this. Auld-Thomas processed the data again, this time using the parameters of his trade developed by the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping.

The result was a detailed map of a sprawling lost city.

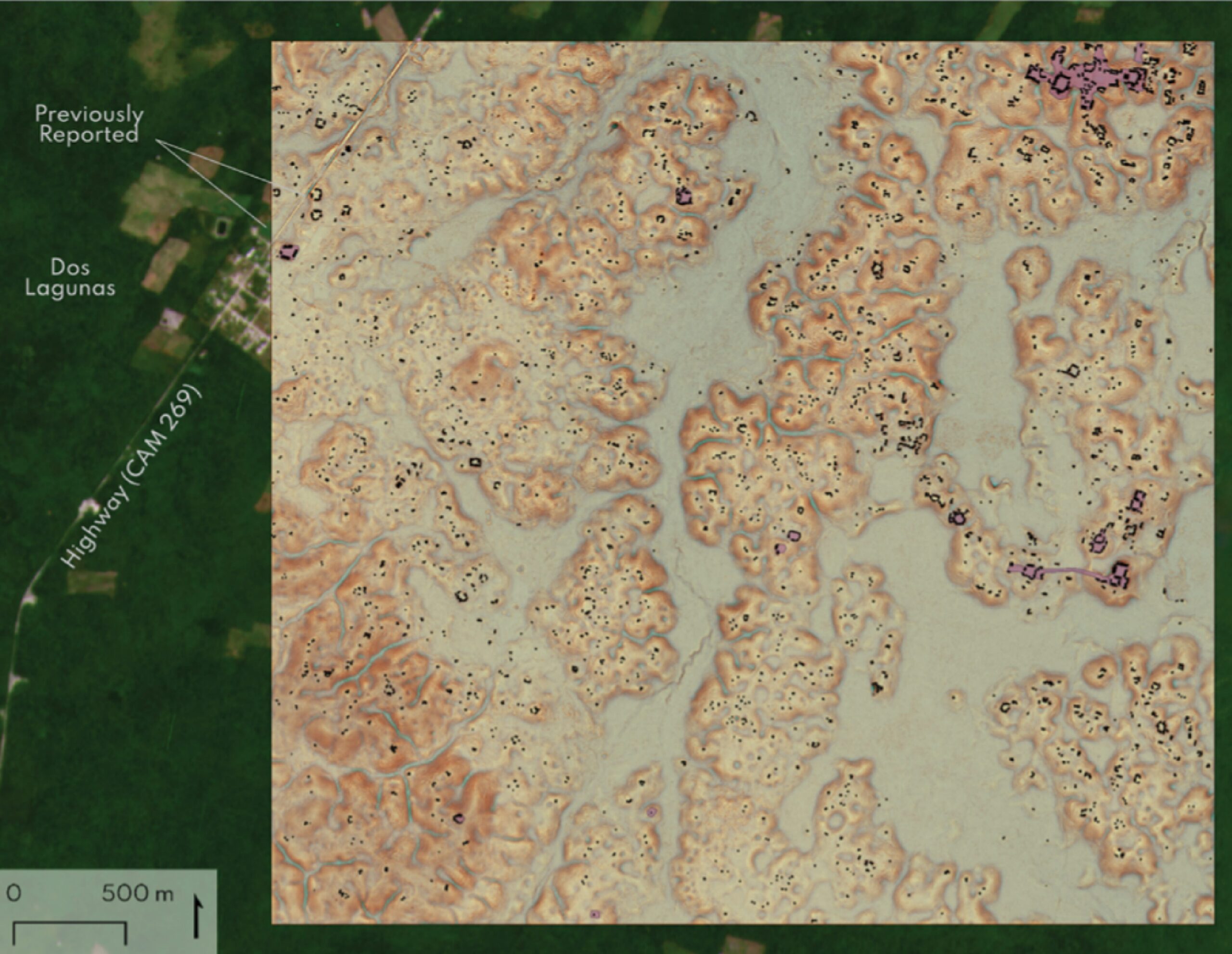

A LiDAR image of the major Valeriana site, with structures in black. Photo: Luke Auld-Thomas/Tulane University

Founded before 150 AD

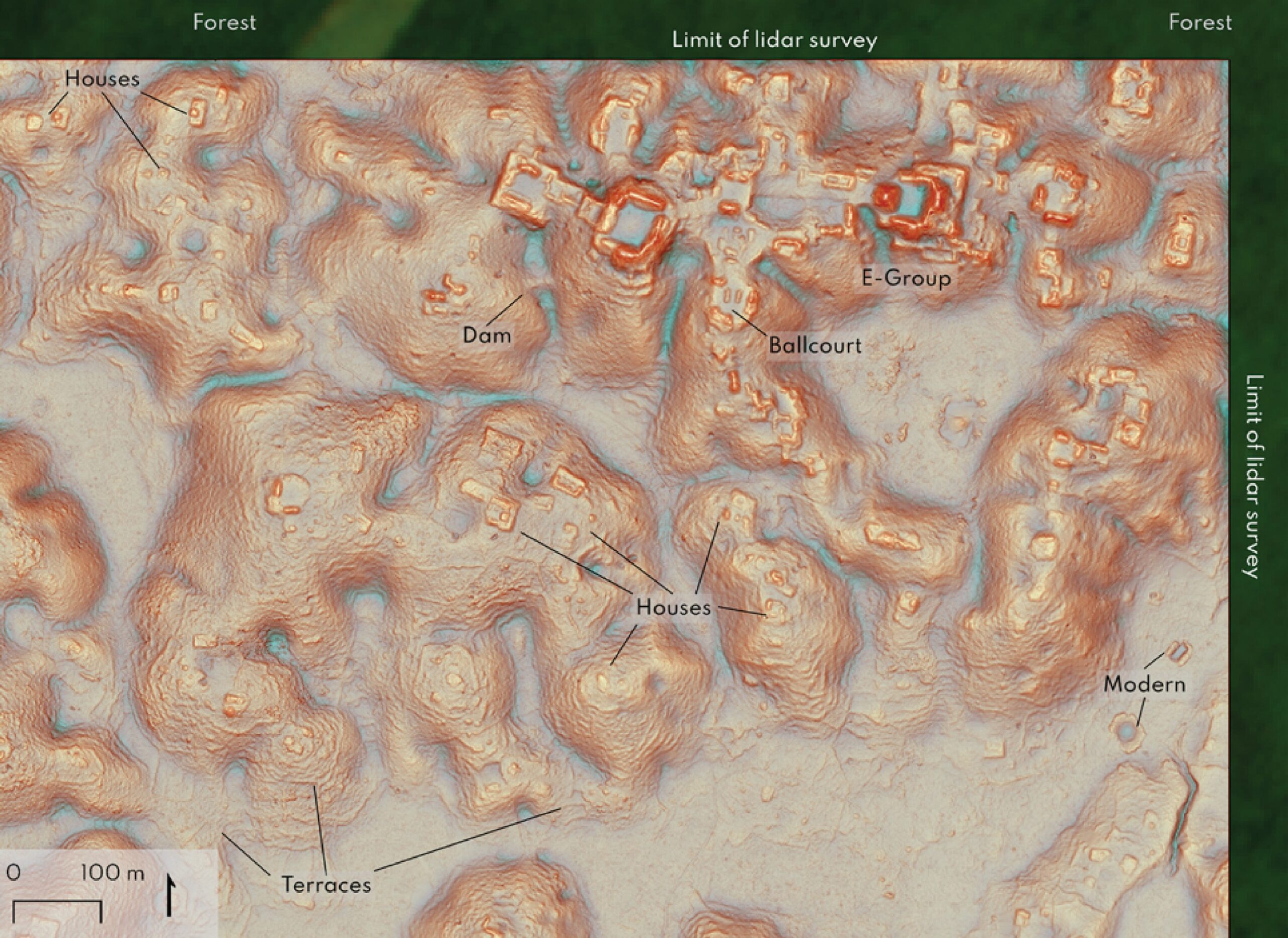

Even without fieldwork, the layout gives archaeologists a glimpse of what life would have been like in Valeriana. At its peak, between 750 and 850 AD, 30,000 to 50,000 people lived there. The city center included several temple pyramids, a ball court, enclosed plazas connected by a causeway, a reservoir and amphitheater-style residential patios. Architectural details reveal that the city was founded before 150 AD, and that the entire site was part of a continuous urban sprawl.

To the southwest of the city center lies a more modest residential area. Here, ring-shaped structures revealed that the people who lived there had been producing lime plaster.

The epicenter of the site is on the edge of the area covered by available data, making it extremely likely that there are more buildings just outside the scanned section.

This discovery is a reminder that in the pre-colonial era, complex civilizations lived in the tropics.

“No, we have not found everything, and yes, there’s a lot more to be discovered,” Auld-Thomas said.

On every level, this discovery runs counter to the old colonial idea of the Americas as a lightly inhabited wilderness.

A LiDAR image of the Valeriana core site. Photo: Luke Auld-Thomas/Tulane University

The future of discovery?

Valeriana also shows us the changing methods of archaeological discovery. Light detection and ranging technology (LiDAR) penetrates dense vegetation. It can search huge, inaccessible areas for possible sites. Until now, its prohibitive cost has limited its use. However, as Luke Auld-Thomas has proved, archaeologists can repurpose so-called ‘found’ datasets from unrelated remote sensing work.

Who knows what ancient, undiscovered wonders are still out there, hidden in old civil engineering reports and ecological surveys?