Scientists have discovered a bizarre creature inside a 99-million-year-old piece of amber from Myanmar. It’s an ancient parasitic wasp with an abdomen that worked like a Venus flytrap. This terrifying insect could open its stomach and snap it shut on unsuspecting prey.

The prehistoric wasp, Sirenobethylus charybdis, offers a glimpse into the brutal world of Cretaceous insect warfare. Unlike modern wasps, Sirenobethylus charybdis had a hinged, pincer-like structure that snapped shut rather than the stinger we associate with wasps.

Photo: Wu, Qiong et al., 2025

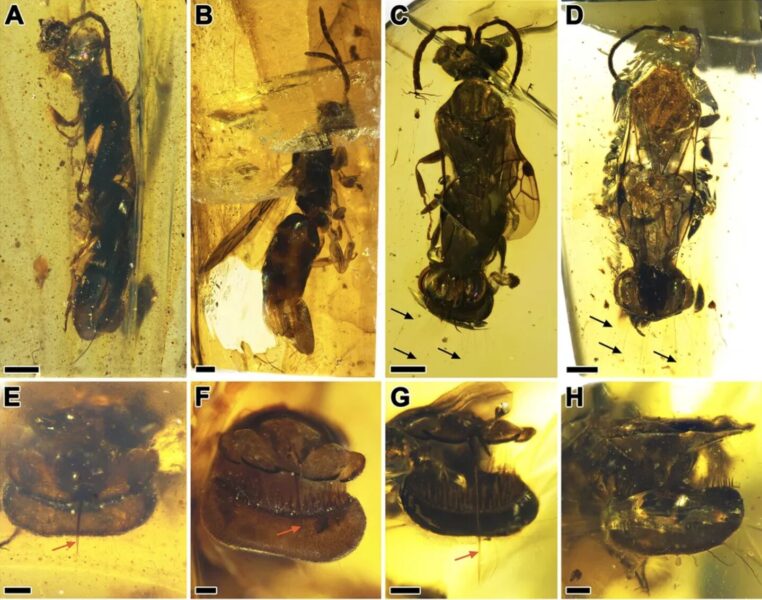

Initially, paleontologists weren’t sure what they were looking at. The study analyzed 16 specimens of the ancient wasp, all encased in amber.

“I thought this must be an air bubble,” study co-author Lars Vilhelmsen told CNN. “It’s quite often you see air bubbles around specimens in amber. But then I looked at a few more specimens and then went back to the first one. This was actually part of the animal.”

In some wasps, the abdomen was open. In others, it was shut.

“It was clearly a movable structure and something that was used to grasp something,” said Vilhelmsen.

Gruesome trap

Most would assume that this gruesome feature was used to trap prey for food, but researchers think it had a wholly different function. They believe the wasps used the hinged abdomen to trap prey and then lay eggs in the subdued host insects.

Once the eggs hatched, the larvae parasitically fed on their host’s body. This is something unseen in the modern world. The closest wasp comparisons are cuckoo and bethylid wasps. Both lay their eggs in the nests of other wasps. The larvae feed on the other wasps’ young as they hatch.

Photo: Wu, Qiong et al., 2025

Scientists struggled to find any insect, living or extinct, with similar features to these ancient wasps. The structure and function of the abdomen most resemble the hinged leaves of Venus flytraps. It consists of three flaps that are covered in small spikes and trigger hairs. These seem similar to the hairs on Venus flytraps.

“What I find extraordinary is that the abdomen of Sirenobethylus charybdis is a brand-new solution to a problem that all parasitoid insects have: How do you get your host to stop moving while you lay your eggs on or in it?” said Manuel Brazidec, an arthropod researcher not involved in the study. “This is a truly unique discovery.”