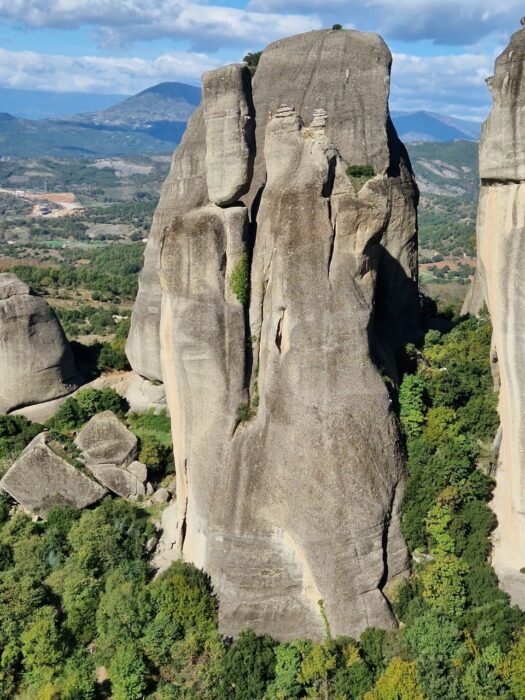

Meteora is a complex of imposing dark rocks, rising over the settlements of Kalampaka and the picturesque Kastraki village, on the plain of Thessaly, Greece. There are approximately 900 multi-pitch climbing routes in the Meteora towers. The texture of the rocks, the fairytale setting, and the fact that every route ends at the top of an outstanding tower make climbing in Meteora a peculiar experience.

One of the surviving, still inhabited monasteries of Meteora. Photo: Monica Malfatti

Meteora’s rocks and climbing style

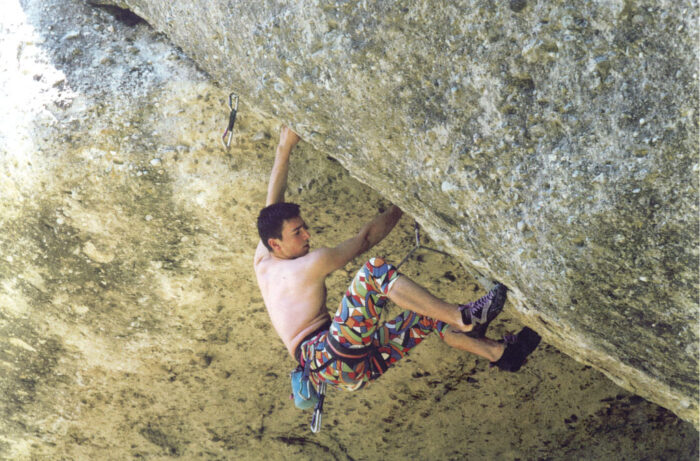

Meteora’s rock texture consists of a combination of pebbles, cobbles, and large rocks attached to a cement-like sandstone and cobblestone rock surface. Shallow holes are often encountered as a result of pebble detachment. When first climbing here, the texture can make the rock feel unstable, especially on downhill pebbles. But gradually, you will learn that the rock is stable.

The slope and the size of the pebbles determine the grade of the routes. Most of the routes are balanced, emphasize technique, and include delicate movements without the need for particularly athletic skills. High grades are considered exceptions. The main traits of the routes are their mixture of slab-based trad and sport climbing.

Climbing on natural holes. Photo: Monica Malfatti

A look back in time

The first climbing records from the Meteora towers trace back to the 10th century, when the first ascetics in the region arrived and settled in the natural hollows of the rocks. The ascetics used scaffolding, nets, and wind ladders for these ascents.

Heinz Lothar Stutte and Dietrich Hasse’s 1975 climbs mark the beginning of modern climbing in Meteora.

By 1985, climbers had established more than 200 routes, and the region had grown popular among climbers and adventurers. Amongst the early Greek climbers, Aris Mitronatsios stands out. Throughout the 1990s, the local climbing community made a significant contribution, establishing new routes and accomplishing challenging repeats. They followed the ethics of ground-up bolting, but installed more bolts than usual because of the difficulty of the routes. A typical example was two young climbers from Kastraki — Christos Batalogiannis and Vangelis Batsios — who made a decisive contribution to the opening of several now classic routes. Action Direct, Orchidea, and Crazy Dancing stand out among them.

By the end of the decade, the local climbing community had grown significantly, with Nikos Gazos and Nikos Theodorou playing an important role in the development of climbing in the region.

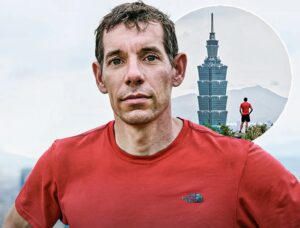

Vagelis Batsios climbing Crazy Dancing, Doupiani, Meteora. Photo: Stefanos Nikologianis

Today, Meteora is a global climbing destination. The Panhellenic Climbing Meeting, for instance, has been held in Meteora since 1988 under the umbrella of the Mountaineering and Climbing Federation, in association with the Kalambaka Municipality and the Kalambaka Climbing Club. This three-day event constitutes a major celebration of climbing each year.

How is it possible?

The giant towers of Meteora are mysterious. One can’t help but wonder how people built monasteries on these summits centuries ago, when climbing them can be problematic even for today’s sophisticated climbers. How, then, did the monks, shepherds, and hunters climb to these summits?

Based on findings from past ascents, researchers believe they started up the vertical sections by driving wooden or iron stakes into the rock. Then, they balanced a wooden ladder upon the stakes, climbed the ladder, wedged more stakes into the rock, and in the end pulled the ladder up to the new stakes, starting again.

The view from one of Meteora’s towers. Photo: Monica Malfatti

The mystery of the cross

However, one of the biggest riddles in Meteora is the metal cross kept at Varlaam Monastery. In 1348, to celebrate his victory over Epirus and Thessaly, Serbian emperor Stephen Dušan ordered a large metal cross (1.80m x 80cm) to be perched atop Holy Ghost, the most imposing of Meteora’s towers. Holy Ghost is a monolithic 300m tower. Climbing to its top involves continuous 5c climbing. Researchers have found no trace of historic attempts on the rock, so we can only assume that somebody climbed 300 vertical metres using just their hands and feet, with no aid whatsoever.

The entrance to Varlaam Monastery, where the cross is now kept. Photo: Monica Malfatti

In 1987, a French film crew led by the famous rock climber Patrick Berhault made a film about Meteora climbing. One of the three rock climbers in the cast attempted to repeat a free-solo ascent of Holy Ghost on the route Pillar of Dreams, 250 meters long and 5c+ as an average grade. Eighty metres above ground, he suddenly changed his mind, and the film helicopter had to rescue him. In 1994, American climber Jane Balister took on the challenge and free-soloed it. Not even James Bond — in 1981, For Your Eyes Only was largely shot in this area — achieved this goal.

Roger Moore playing James Bond in Meteora. Photo: Screenshot from For Your Eyes Only, 1981

Then, climbing happened, thanks to the Germans

Dietrich Hasse was born in Bad Schandau, Saxony, and from a young age, he was involved in climbing. He quickly became one of Elba’s best climbers. He opened many new routes and explored the Dolomites with excellent climbing partners, such as Lothar Brandler (known for the Hasse-Brandler route on the North face of Cima Grande di Lavaredo), Claude Barbier, and Heinz Steinkötter. In August 1975, Hasse and Sepp Eichinger visited Meteora for the first time. They were struck by the imposing towers and established the first four routes in the area.

In the spring of 1976, Hasse and his friend, professional climber and photographer Heinz Lothar Stutte, established even more climbing routes in the area. In 1977, they published the first climbing guide for the region, listing 83 routes.

Interest amongst the German climbing community was growing and seemed to reach a peak with the ascent of the eastern side of Alyssos tower. Hasse, Eichinger, Mägdefrau, and Lothar Stutte opened the Community Path route in a three-day effort, from March 27 to March 30, 1978.

Hasse died in 2022. Two years later, Greek climber Vangelis Galanis made a rope solo first ascent of a new multipitch route on Kapelo Peak and dedicated it to Hasse.

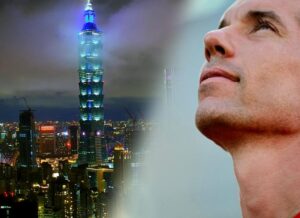

Meteora. Photo: Monica Malfatti

How to get there

From Athens, Meteora is 360km by car (in the direction of Lamia, Domokos, Karditsa, Trikala, and Kalambaka) on a route well serviced by intercity buses and train services. From Thessaloniki, the distance is 230km, by two main routes. The first leads to Kalambaka through Katerini, Larissa, and Trikala. The second goes via Veria, Kozani, Grevena, and Kalambaka. Both routes are possible by intercity bus and train.

You can also reach Meteora from Igoumenitsa, it is a 150km road through Loannina and Panagia. From Volos, it is 140km through Larissa and Trikala. Both routes are served by intercity buses.

An example of the extraordinary verticality that characterizes Meteora’s towers. Photo: Monica Malfatti

Where to stay

The finest place to stay for climbers who want to explore the entire area is Kastraki, which lies between Meteora Towers. Small hotels, rental rooms, and two campsites are available there. Several lodgings are also offered in Kalambaka, a neighbouring town around 2km from Kastraki. I particularly recommend Ziogas Rooms, Thalia Rooms, Hotel Kastraki, and Camping Kastraki.

You can find a supermarket in the town of Kalambaka, and you can purchase basic supplies in a mini-market in Kastraki.

The view from the walls. Photo: Monica Malfatti

When to find perfect conditions

Climbing conditions are best between April and the middle of June, and from the middle of September to the end of November. The surroundings are lush in spring, but there is a greater chance of rain compared to hot and dry fall. Although summer can be quite warm, some routes are in the shade for a long time during the day. Though winter is more challenging, climbing is still an option on sunny days.

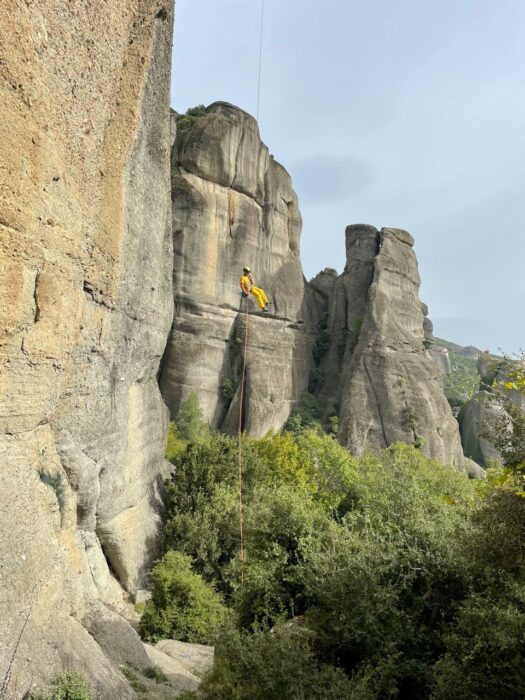

Rappelling down from Meteora’s towers. Photo: Monica Malfatti

Gear, rules, and final recommendations

In addition to personal climbing gear such as a climbing harness, climbing shoes, a belay/rappel device, carabiners, straps, a lanyard, some nuts, and some friends, it is suggested you take 10-16 quickdraws. Two half-ropes of 60m will help with multipitch climbing, or a 70-80m single rope works for sport climbing.

In April 1976, the Archeological Service and the Orthodox Church granted written permission to climb in Meteora. Climbing is only forbidden on the six towers with inhabited monasteries. Rock climbing is thus permitted without restriction on the remaining 50 solid towers and 80 smaller ones. Campfires, camping, or bivouacking between the towers is strictly prohibited.