On August 24, 79 CE, Mount Vesuvius erupted, burying the nearby town of Pompeii in ash, suffocating the inhabitants and preserving a complete Roman town in the middle of a normal day.

Actually, everything in the above sentence is either outright false or a matter of speculation. The citizens of Pompeii and neighboring towns like Herculaneum and Oplontis did have some time to evacuate, and many, most likely the majority, did so. Of those who were killed, most did not suffocate on ash but were killed by the intense heat, by falling debris from earthquakes, or even from the resulting tsunamis.

And it possibly didn’t happen on August 24. We don’t have the original copy of Pliny’s letter, the only contemporary account that gives an exact date. We only have medieval manuscript copies, which could very plausibly have confused the Roman calendar system.

Meanwhile, much of the physical evidence suggests it was late autumn, not late summer. Victims wearing heavy cloaks and fresh wine suggest the grape harvest had already taken place. Prevailing southeasterly winds, like those described during the eruption, are common in Campania during late autumn but very rare in summer.

The 79 CE eruption of Mount Vesuvius is firmly established in our cultural consciousness. But our general understanding lags behind archaeological evidence. Here, we consider a few more misconceptions and highlight some interesting finds and unsolved mysteries.

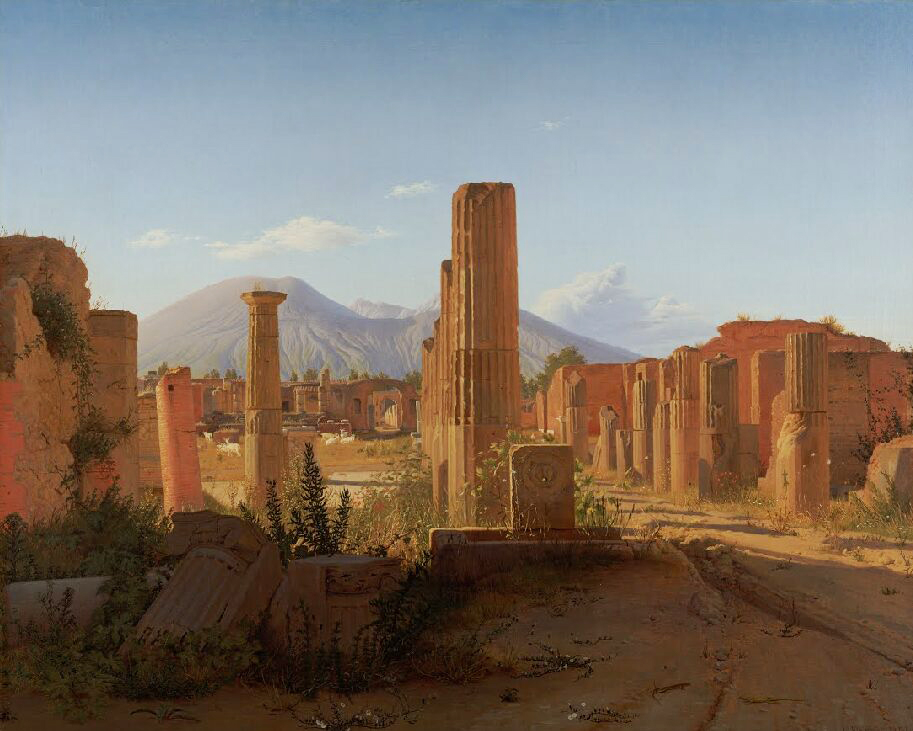

‘The Forum, Pompeii, with Vesuvius in the Distance’, Christen Kobke, 19th century

Pliny the Elder at Pompeii

It’s generally understood that only one well-known figure died in Pompeii.

Known in his own time as Gaius Plinius Secundus, Pliny the Elder was an author, government official, and naval commander. His monumental Naturalis historia, an encyclopedic compendium of natural history, medicine, and geography, was groundbreaking. It was also almost completely wrong about everything. Widely read and cited for centuries after his death, Pliny’s work crops up wherever one discusses ill-advised ancient remedies or strange myths of the classical and medieval world.

Pliny was Emperor Vespasian’s naval admiral at the time. The account of his death comes to us from his nephew, also called Pliny. Pliny the Younger, writing to the historian Tacitus years later, tells us that he and his uncle were at his mother’s home in Misenum when they saw the black plume of smoke rising.

The older Pliny went to investigate, soon receiving an urgent message from his friend Rectina. She lived at the foot of Vesuvius and was unable to evacuate by land. Pliny quickly organized Rome’s navy into a rescue fleet and made for Vesuvius. On the way, he is recorded as having a quite famous conversation. When the pilot advised him that proceeding would be dangerous, and asked if they should head back, Pliny replied that “Fortune favors the bold,” and proceeded.

He immediately disproved his own statement by dying.

‘Death of Pliny the Elder’, by Ricardo Marti, 19th century

Questions remain about the death of Pliny

It went like this: landing at the town of Stabiae, about four kilometers from Pompeii along the Bay of Naples, Pliny took charge of the evacuation. Panic was widespread, but the old general was calm and deliberate. As the eruption flung stones and debris into the air, Pliny directed everyone to tie pillows on top of their heads for protection.

Pliny led his people along the shore, searching for a place to safely put to sea and evacuate the terrified civilians. The waves were too wild and, on the stormy shore with fire all around, Pliny began to act strangely. He was lying on the ground, drinking water, when the fire grew closer, and everyone began to flee. Two of his servants tried to help him stand, but he “instantly fell down dead,” and they were forced to leave him. Three days later, his nephew reports, his body was found “without any marks of violence upon it.”

His fleet, meanwhile, did manage to launch and may have saved as many as 2,000 people. To this day, we aren’t entirely sure what killed Pliny. His nephew conjectures that smoke inhalation may have been to blame, a dominant narrative until the modern era.

In the 1850s, however, historian Jacob Bigelow re-examined the accounts of his death. Bigelow checked the original Latin and reviewed the geography and concluded that Pliny had not been nearly close enough to suffocate. Instead, his already poor health and the stress of the event likely caused him to have a heart attack, many historians now believe.

So, the most famous man to die in Pompeii wasn’t at Pompeii and probably wasn’t even killed by the eruption.

A villa of Stabiae. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A Biblical princess

As I mentioned above, few people died in the eruption whose names we know from other contemporary sources. Pliny is the big one. One of the friends he tried to rescue, Roman senator Pomponianus, is another. They died at nearby Stabiae, but Princess Julia Drusilla died in Pompeii itself.

The daughter of Herod Agrippa, the last king of Roman Judea, Julia Drusilla was first married to the king of a Roman client state in what is now Syria. But soon after, she met the Roman Governor of Judea, Antonius Felix. According to contemporary Jewish historian Josephus, Felix was determined to marry the beautiful young princess. He sent an emissary who convinced her to dissolve her first marriage and marry Felix, despite the fact that he was a pagan. He succeeded, and they married.

It was during her time as the wife of Antonius Felix that she appears in the Bible. Acts 24:24 describes how, when Felix confronts an imprisoned Paul the Apostle, his wife Drusilla accompanies him. She had a son with Felix, named Marcus Antonius Agrippa. Years later, they were both in Pompeii during the eruption where, Josephus reports, they perished.

Drusilla appears in depictions of the trial of Paul, seated or standing beside her husband. Photo: The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn Archives

After the eruption, people came back

While we imagine the eruption as the final days of Pompeii, some survivors did return. While much of the city was buried, it remained a site of settlement for several centuries.

Only last year, a team of archaeologists led by Gabriel Zuchtriegel released new research confirming that Pompeii was resettled. Survivors who couldn’t afford to start their lives over somewhere else returned to their ruined homes. They were joined by desperate treasure hunters, hoping to loot valuables from the buried city.

While pre-eruption Pompeii was a thriving, wealthy town, post-eruption Pompeii was far more precarious. The bottom floors of buildings became the new cellars. The upper floors, which still protruded from the ash and debris, became the ground floors. They benefited from none of the infrastructure of a Roman town, but many had nowhere else to go. As vegetation returned, they settled into their strange new old city and remained there for hundreds of years.

Pompeii appears in the Ancient Roman road map, the Tabula Peutingeriana, which was being actively revised into the early 5th century. For Pompeii to be included, the 5th-century cartographers must have considered it to still be an active settlement.

There was another spate of eruptions in Late Antiquity, and after that, Pompeii was finally abandoned. Now, archaeologists think their 18th and 19th-century predecessors may have accidentally erased much of the evidence of this later occupation, in their enthusiasm for Pompeii’s earlier splendor.

Pompeii appears in this modern facsimile of a medieval copy of a 4th to 5th-century map. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ancient cult ceremonies

Some of the greatest Pompeian discoveries are painted, or scrawled, onto its walls. A wealth of well-preserved frescoes lets us peer into the lives of the elites, while the abundant graffiti presents a rare insight into the minds of everyday people. But the wall paintings in the Villa of Mysteries go further, offering a tantalizing glimpse of the ancient world’s most closely guarded ritual secrets.

Mystery cults were religious groups whose practices and rites were kept secret and only revealed to the initiated. A cultural inheritance from ancient Greece, many Romans were involved in the Dionysian Mystery cult. Despite its massive popularity, we still have only vague ideas and surmises regarding the rites. But archaeologists believe that the vibrant frescos in a massive Pompeian villa depict one of these secretive initiation rituals.

The opulent 60-room villa, situated just outside the city’s main gates, was uncovered in 1909. The walls of one room, a dining space, are adorned with over two dozen life-sized figures against a vibrant red background. According to the most accepted interpretation, the frescoes form a narrative sequence, depicting one young woman — the initiate — undergoing the Bacchic rites, possibly in advance of her marriage.

Another similar fresco was discovered only last year, in an insula at the center of Pompeii. A press release by the archaeological team confirms that this fresco shows Dionysian rites, this time a single procession of frenzied worshippers, nymphs, satyrs, and another young woman initiate.

The initiate, right (or possibly a goddess) looks on as satyrs, nymphs, and goats do…well, it isn’t super clear. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The skull and jawbone of Pliny?

What we’ve found about the destruction that occurred that day in 79 CE is staggering, but what we still need to discover is even more tantalizing. Ash-encrusted remains can only reveal so much.

Who, for example, are the two young people locked in an embrace, long believed to be sisters but recently shown, through genetic testing, to be unrelated and, for at least one of them, not women? Who wrote “Phoebus — May you fall ill,” on a wall in Herculaneum? And what did Phoebus do to make them so mad? Who is the person whose skeleton was found on the beach by Stabiae?

Well, that one is Pliny the Elder. Unless it isn’t. Thousands of years after the eruption, an Italian engineer named Gennaro Matrone owned an estate which had been part of the beach of Stabiae. His favorite hobby was digging up his own land, looking for ancient treasure. Around the turn of the twentieth century, he uncovered over 70 ancient skeletons. One of them wore golden necklaces and an opulent ivory-and-seashell-handled sword.

Matrone announced to the world that he had found Pliny the Elder, and the world largely responded with derision. Disappointed, Matrone sold off much of his find and reburied the rest, except the skull and jawbone of the alleged Pliny, which went to a small Roman museum.

A century later, historian Flavio Russo pointed out that the museum still had those bones, which might be testable. In 2020, the Museo dell’ Arte Sanitaria released the results of those tests: the skull and the jawbone didn’t belong to the same person.

The skull and jawbone in question. Photo: Luciano Fattore

The skull of Pliny?

The jawbone belonged to a person in their thirties. Isotopic analysis of the teeth showed that they had spent time in Pliny’s home region of Como. But Pliny died in his mid-fifties. The skull, however, was slightly more promising. Age is one of the traits we can most reliably determine from a skull. This one belonged to a person in their 40s or 50s.

So, someone in the right place, of the right age, and the right social status. The case is not exactly strong, especially when you consider that Stabiae was a wealthy area, where lots of people had nice jewelry. Moreover, there is the matter of his nephew’s letter.

From Pliny the Younger’s writing, it is clear that he had a great deal of affection and regard for his uncle. If, as his letter suggests, his body was found and its exact location and state were reported to the living Pliny, wouldn’t the young man have his uncle’s body retrieved and buried? Like many cultures, the ancient Romans had a particular horror of unburied bodies. A person whose body wasn’t properly attended might be condemned to wander the earth as a restless spirit.

On the other hand, as Classics professor Roy Gibson suggested in an Oxford University Press write-up, Pliny the Younger may have had other reasons to assert that Pliny the Elder’s body had been discovered. A rumor went around, according to contemporary historian Suetonius, that Pliny had asked a slave to kill him, fearing the pain of death. The Younger carefully described his uncle’s uninjured body in order to counter this rumor.

So maybe this skull may or may not have belonged to Pliny. As with so much else about that disastrous eruption, we’ll likely never know for sure.