As a teen, road trips to Dorset meant three things: Moores biscuits, swimming at the Durdle Door arch, and fossil hunting. We visited the seaside towns of Lyme Regis and Charmouth for exquisite fish and chips and then long walks among the fossils dotting the shoreline.

From Exmouth in Dorset to Studland Bay in Devon, the rugged coastline exposes millions of years of rock from the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods. For amateur paleontologists or curious visitors, it is a fossil-hunting goldmine.

Mary Anning, a pioneering fossil collector. Oil painting by Joseph Anning.

Where it all began

Mary Anning combed the beaches with her trusty spaniel, Tray, in the 1800s. Anning grew up in Lyme Regis, the daughter of a carpenter. Money was tight, not just in the Anning household but throughout the community. Locals knew the beaches were replete with interesting objects: large teeth, bones, spiralling shells embedded in rock, and other remnants of the area’s ancient past. Many locals sold these finds, claiming they had magical properties.

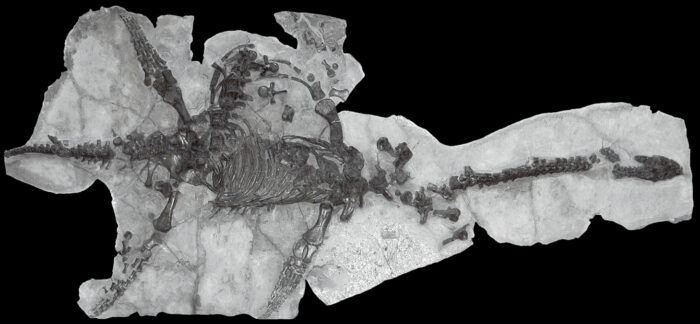

Anning’s family would go to the beach and collect fossils to sell. Anning taught herself about dinosaurs and other extinct species. At just 12, she found the first-ever skeleton of an ichthyosaur, which she sold to nobleman Henry Hoste Henley for £23. Ichthyosaurs were large reptiles that roamed our oceans during the Mesozoic Era. With long snouts, fins, and a tail, they resembled dolphins.

Word got out that the Anning family business provided fine fossil specimens. But despite their newfound fame, the family couldn’t pay the bills consistently. Soon after, when Anning’s father passed away, things looked increasingly dire. Anning was forced to take over the family business, but she continued to find skeletons, including plesiosaurs and a pterosaur.

Though now well-known, Anning was never officially recognized for her contributions to paleontology. London’s scientific establishment refused to acknowledge her.

In the words of Lady Harriet Silvester, who met Anning during a visit to Lyme Regis in 1824:

The extraordinary thing in this young woman is that she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones, she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved…It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favor that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.

Types of fossils

There are two main categories of fossils:

Category I fossils include new species (or specimens that may represent new species) and fossils that display exceptional preservation. These fossils are extremely rare, such as the Charmouth dinosaur Scelidosaurus.

Category II fossils include partial or complete vertebrates such as reptiles and fish. Nautiloids and certain ammonites are also included here.

A girl collects fossils on the beach. Photo: Shutterstock

From ammonites to ichthyosaurs

Along the Jurassic Coast, most fossils are of aquatic creatures. The most common and abundant fossils are ammonites. In the medieval period, ammonites were nicknamed “snakestones” after people mistook them for fossilized snake coils, which supposedly had healing powers. Rather, they are spiral-shelled cephalopods, distant relatives of modern squid and octopuses. You can find them inside or on top of shale rocks, which you can easily chip off with a hammer and chisel. If you don’t have a hammer on hand, you can use another rock to get the job done.

Belemnites are the second most common fossils along the Jurassic Coast. These are tube-shaped fossils nicknamed “devil’s fingers.” They resemble bullets and are the shells of an extinct species of squid. People used to grind them up as a rheumatism cure. Brachiopods and bivalves are also abundant and look similar to regular seashells.

Ichthyosaurs left behind their skeletons, most commonly their vertebrae. These can be tricky to identify: they look like thick, disk-shaped rocks.

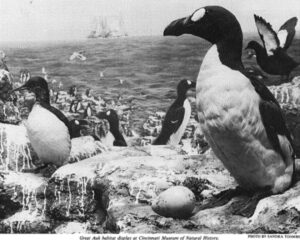

Plesiosaurus found in Lyme Regis. Photo: Paleo_bear/Flickr

Shark teeth are sharp, pointed, and often triangular. They are dark in color (black, brown, or grey) because of mineralization over millions of years.

Fossilised sea sponges and urchins are also very common. Identifying them is easy, as they have not changed from the ones we know today. The same goes for plant fossils, which were once ferns and cycads. As for fish, you’d be extremely lucky to find the elusive and rare dapedium, a broad, discoidal fish fossil.

Protocol and equipment

As a hobby, fossil hunting doesn’t require much beyond a keen eye and maybe a hammer. The rest is luck.

The good news is that fossils collected on the Jurassic Coast are free for the taking. There’s no limit to how many you can collect, though you cannot collect from protected scientific sites (Sites of Special Scientific Interest) without permission. Heavy machinery is forbidden, and only small hand tools are allowed.

Ammonites, belemnites, and other fossils. Photo: Shutterstock

Safety is important; the Jurassic Coast features eroding cliffs that are prone to landslides. Fossil hunters should steer clear of the cliffs and stay on the foreshore and shoreline. Mary Anning’s dog, which died during a landslide, is a cautionary example of the risk.

Strong winds, thunderstorms, and rough seas make the coastline dangerous. It is important to read the weather and tidal reports. The waves make the fossil forests slippery and sweep most of the fossils into the sea.

Category I specimens should be reported to academics, and a museum may make an offer to buy them from the collector. Here’s what the official Lyme Regis fossil hunting website says:

Any fossil found on the beach is yours to keep. The fossils found on the shore do not last. The next storm or the crashing sea can destroy them. If an interesting or rare specimen is found, then I would encourage you to take the fossil to the Lyme Regis Museum, where the fossil will be photographed and recorded. In exceptional cases, the details are forwarded to the Natural History Museum in London. Many such finds have been donated to the local and national collections.