For Arctic residents and a few polar addicts, icebergs are familiar. I’ve skied, paddled, and boated past thousands of them. But most of us have just seen photos of these beautiful ice sculptures and may have only a vague idea where they come from. Here’s a primer on one of nature’s great art forms — how they’re made, how they differ from ice floes, and the many forms they come in.

Icebergs come from tidewater glaciers, above, that end in the ocean. As the glacier moves forward, pieces break off and drift away as icebergs. Devon Island, Canada. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Glaciers that do not end at the water’s edge, above, cannot spawn icebergs. Dundas Harbour, Devon Island. Note, however, the small iceberg from another glacier drifting in the lower right. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Another tidewater glacier, a source of icebergs. Jokel Fiord, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Glaciers don’t need to terminate in an ocean to create icebergs. Berg Lake in the Canadian Rockies, background, sometimes has a few small icebergs from the alpine glacier that plunges into the lake. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Immobile icebergs

Most of the year, icebergs are frozen into the sea ice. The moat around an iceberg has thinner ice and draws local wildlife like seals. As a result, arctic wolves and polar bears often investigate icebergs. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Jones Sound, off Ellesmere Island, in early July. Meltwater puddles on the sea ice eat away at the connective tissue, eventually breaking the continuous sea ice into individual floes. By now, a moat of open water surrounds the iceberg in the center, which will eventually drift away from its sea ice prison. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

In Greenland’s famous Ilulissat Icefiord, the icebergs are so densely packed that you sometimes have no space between them. Ten percent of all Greenland icebergs come from the glacier at the head of this fiord. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Tourists on the boardwalk at the Ilulissat Icefiord. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Arctic art

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Iceberg triplets off Northwest Greenland. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Icebergs near Qaanaaq, Greenland. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Keyhole icebergs are fairly common. The keyhole is part of a drainage channel in the parent glacier. Though tempting, boaters should never go through the keyhole of an iceberg: It’s Russian roulette. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

In the cold season, peeking into the keyhole of a frozen-in-place iceberg is a lot safer. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

A drainage channel beneath a glacier that may one day become part of a keyhole iceberg. During summer, water drains from the surface of the glacier through a vertical melt shaft called a moulin. This meltwater becomes a subterranean river beneath the glacier, eventually boring a subway tunnel through it. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Icebergs vs ice floes

An iceberg and sea ice are not the same thing. An iceberg comes from a glacier and is freshwater. Sea ice is frozen ocean. It is usually flat, except near shore, where tides break and push sea ice into choppy sections — but nothing as big as an iceberg. Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

This is not an iceberg but just a piece of old sea ice tilted upward and probably grounded in the shallows. The ‘dagger’ part used to rest flat on the ocean surface. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Sea ice breaks up in summer and forms ice floes (not ‘flows’). Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Ice floes shortly after breakup are often thick enough to walk on, even when they’re free-floating. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

More ice floes. Sand Bay, western Axel Heiberg Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Ice floes can be the size of a floor mat or many kilometers long. Their undersides are rich in small marine life. This draws seals, which in turn makes them popular platforms for polar bears in summer. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Multiyear ice: also not icebergs

Multiyear ice used to be common in the High Arctic but is rare now. These pieces are all very old, extra-thick floes, built up over many years and pressed up by currents and tides. They are not icebergs. Robeson Channel, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

More multiyear sea ice (the pressed-up stuff). The flat surface in between is first-year sea ice. No icebergs in this picture. Baird Inlet, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Icebergs frozen into Nansen Sound, between Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg Islands. First-year sea ice, which will break into ice floes in July, lies between the bergs. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

The Antarctic has many so-called tabular or flat icebergs, which break off from the giant ice shelves ringing the continent. The Arctic has fewer tabular icebergs, but still some. Above, a tabular iceberg off Baffin Island. Note how the top of the iceberg sits much higher out of the water than an ice floe does. For scale, the distance between the open ocean and the flat top of the iceberg is about seven meters. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

There used to be half a dozen ice shelves off the north coast of Ellesmere Island. A mix of glacier ice and sea ice, they typically had those corrugations. Periodically, pieces of ice shelf broke away and drifted over the Arctic Ocean as super-icebergs called ice islands. They survived for many years and occasionally served as stable platforms for science camps. All or almost all the ice shelves are gone now. Ward Hunt Ice Shelf, Ellesmere Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Most Arctic icebergs come from Greenland. They drift over to the Canadian side with the currents and float southward down what’s called Iceberg Alley, dwindling as they go. Above, an iceberg off the Labrador coast. Icebergs have reached as far south as Bermuda. The iceberg that sank the ‘Titanic’ was off the coast of Newfoundland. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

A dangerous beauty

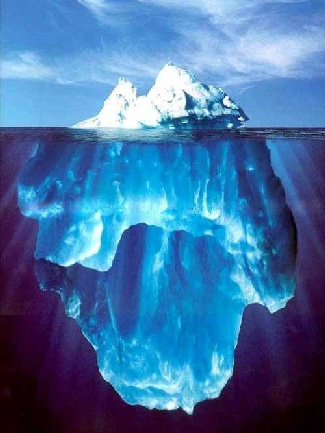

As this popular online illustration shows, most of an iceberg lies below the surface. When the iceberg melts, the changing balance may cause it to flip suddenly.

Icebergs can be as dangerous as they are beautiful. As a rule of thumb, boaters should not approach closer than twice the distance of an iceberg’s height. See video below.