The deep guttural roar of a stag echoed across the loch, rolling from one valley to another. I lay in my tent, half-awake, the sound somewhere between a bear and a large cow. All night, these alpha-male performances counterpointed the quiet, shadowy hulks of mountains, as stags traded auditory blows from one valley to another.

Earlier that week, I’d set out for six days of solo packrafting across the waterways of a region known as Assynt in northwest Scotland. This was my first packrafting trip, and by now, I’d shaken off my early jitters. Traveling solo with limited open-water experience carried some risk, but the two-kilo packraft offered a new way for me to explore one of Britain’s most revered mountain landscapes.

Suilven (731m). Photo: Shutterstock

Packrafts first appeared in the 1980s as inflatable boats light and compact enough to carry in a backpack. Originally used by a small community of Alaskan adventurers, they offered a new way to link rivers, lakes, and trails on long wilderness journeys. The packraft is arguably one of the most innovative developments in outdoor gear in the past 30 years.

While there are premium packrafts on the market, this one only cost around $300 and is more than capable of this kind of journey. Photo: Ash Routen

The packraft revolution

The early oval designs were made for quick turns in whitewater rather than straight-line travel, but today’s narrower models track much better. A packraft would give me flexibility in navigating Assynt’s landscape, which is dotted with nearly 700 lakes, known locally as lochs.

There are almost no footpaths here, and the ground is a blend of bog, tussocks, and undulating rocky ground, so one of the best ways to travel is by water.

The ancient glacial landscape of Assynt, with Torridonian sandstone in the foreground. Photo: Shutterstock

The trip began with a 10-hour drive north from my house in the Midlands of England. Big, multi-armed motorways eventually shrank to a single ribbon of road. Leaving my car in the hamlet of Elphin for the week, I walked down the road to Loch Veyatie, my entry to the mountains.

Before launching the packraft, my nerves tightened a little, a mix of my inexperience and the headwind whipping the loch. I’d done my homework, practiced on local streams and lakes, and read up on packrafting. I’d even — don’t laugh — analyzed a packrafting fatality list and written about it.

On open water, for example, you needed to avoid getting separated from your raft after a capsize. To mitigate risk, I leashed my paddle to the raft to give me a better chance of holding onto both if things turned south. I also strapped my 15kg backpack securely in the bow.

A dicey beginning

Still, the first hundred meters on the water were tense, as waves slapped the raft broadside. Progress remained hard-won and slow because of the wind, but eventually I found a rhythm. After three-and-a-half kilometers, I pitched my tent on a stony beach, with the mountain of Cul Mor rising to the left and Suilven’s shark-fin ridge dominating the horizon to the right. I was underway.

On the shore of Loch Veyatie. Photo: Ash Routen

For 20 years, I’d wanted to travel the far northwest of Scotland, ever since clapping eyes as a teen on a photo of Suilven in a hiking magazine. The peaks of the Assynt and Coigach region aren’t tall by global standards. Even in the UK, they don’t have the prestige of, say, the Munros. But what the area lacks in height, it makes up for in wildness and mystique.

Assynt sits within the Northwest Highlands Geopark, a UNESCO-recognized area with some of the oldest rocks in Europe. Lewisian gneiss in the loch-strewn lowlands is around three billion years old, while the Torridonian sandstone peaks of Suilven, Cul Mor, and Stac Pollaidh are relatively young, “only” a billion years old.

These isolated mountains rise abruptly from the lowlands, creating a place that feels ancient, empty, and unlike any other mountains in Europe.

Possessed

Scottish poet Norman MacCaig, who claimed to have been “possessed” by the landscape of Assynt, once wrote:

Glaciers, grinding West, gouged out

these valleys, rasping the brown sandstone,

and left, on the hard rock below — the

ruffled foreland —

this frieze of mountains, filed

on the blue air — Stac Polly,

Cul Beag, Cul Mor, Suilven,

Canisp — a frieze and

a litany.

For centuries, crofters (subsistence farmers) eked out a living here, fishing and grazing sheep. Many of those settlements closed during the 18th and 19th centuries, and today, the area is sparsely populated, with more deer than people and more ancient ruined walls than intact homes.

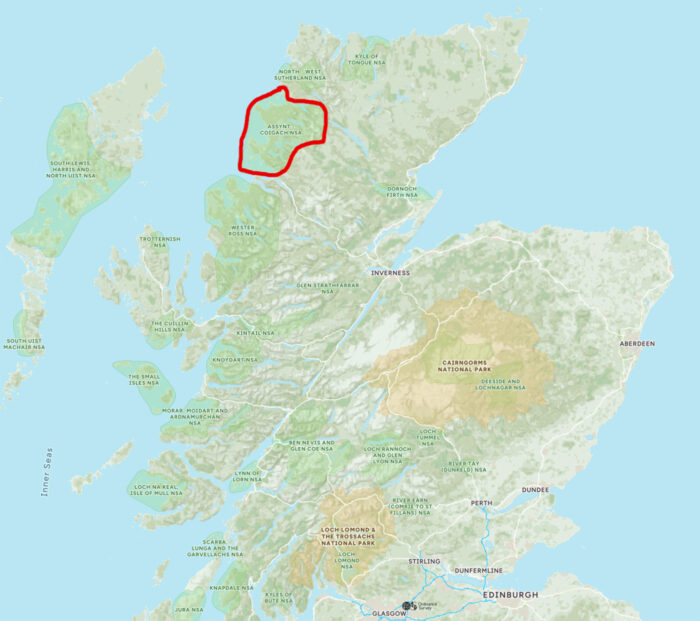

Assynt and Coigach, circled in red. Map: OS Maps

A glacial pace

The next morning, I launched into the loch again, despite the unsettled weather, but quickly realized how strong the headwind was. Progress was glacial. It took more than half an hour to cover one kilometer. Eventually, I gave up and set out on a punishing overland detour over boggy tussocks and sodden ground. Instead of trying to stick to the rocky shoreline and risk getting cliffed out, I cut inland, closer to Suilven and its steep, unwelcoming flanks.

In the afternoon, I reached a faint path skirting the next body of water, Fionn Loch. The trail was little more than a waterlogged line through bog, but it offered direction. By 3 pm, I had pitched camp on a stony beach. For a second day, I had covered a modest distance, just eight kilometers of considerable effort. The silhouette of Cul Mor loomed across the water as I made dinner and dried what kit I could.

Cutting inland on foot with Suilven beginning to fill the horizon. Photo: Ash Routen

Clear skies and calm water

Although the start of my journey had been slow, the low wind and clear skies in the forecast should now improve progress. Portaging three kilometers from Fionn Loch to the larger Loch Sionascaig, I soon found that dragging the empty raft like a sled while backpacking my gear was the most efficient method. The ground was mainly bog and grass, so it was unlikely I’d puncture my boat.

The mountain of Cul Beag reflected into a lochan (a smaller loch). Photo: Ash Routen

By late September, Assynt is a land in transition. The heather begins to fade, bracken reddens on the hillsides. The craggy shoreline and slight hint of salt in the air (the sea was only a few mountains away) gave a distinctly maritime feel. Easy paddling across Loch Sionascaig took me past small islands along the shoreline. The larger islands look inviting to camp on, but I’d read they were often tick-infested, and dense low bushes left little room for a tent.

Better progress

The water smoothed out as I portaged to a small loch and lochan — more pond than lake. I’d made better progress in the benign conditions and camped on a beach with deer prints etched in the sand. A stag in rut called out from a small woods nearby.

A stag in the Scottish Highlands. Photo: Shutterstock

At night alone in a tent, the roar of another stag carried across the water, answered from another glen. It felt ancient and raw, a sound that belonged entirely to this landscape.

On the clear, cold morning of the fourth day, the surface of Sionascaig lay mirror-still. I deliberately paddled into every inlet to soak in the landscape, rather than hurrying past as I often do when long-distance hiking or skiing.

A beachside camp with the mountain Cul Beag in the background. Photo: Ash Routen

Moments of awe

The view from my packraft was cinematic. The silvery water reflected the sandstone towers and heather slopes above. I rarely feel awe in the mountains, but here I was, experiencing the most perfect autumn weather, a scene so undeniably Scottish — crystal water, green glens, and grey mountains. Like the stags the night before, the land was roaring evocatively.

If you’ve ever heard a lone bagpiper blast out a tune, you’ll know there is something about Scottish culture that stirs the soul. To me, it’s not the people that drive this, it’s just a reflection of the landscape. It makes you want to sing and dance a highland jig. I guess that’s what I’d call my version of awe.

Perfect weather on Loch Sionascaig. Photo: Ash Routen

Although I had two days left, across Ffion Loch and then back to Loch Veyatie, I was already sold on this means of travel. It had its gripes, as all travel does — dragging the empty raft on those portages too short to deflate and reinflate it, for example.

But the ease of water travel without a pack weighing me down was addictive. In winter, I enjoy skiing while pulling a sled for the same reason. It didn’t even bother me much that I didn’t climb a single peak. Suilven, the mountain that had drawn me to this part of Scotland all those years ago, would have to wait for another visit.

A distant Suilven reflected into the calm waters of Loch Veyatie. Photo: Ash Routen

Homeward bound

I wondered why I had spent years chasing more distant, exotic places when, in truth, I could not imagine a more rewarding adventure. Assynt felt like home. That afternoon, I drove 40 minutes south to the small village of Ullapool. I bought fish and chips and ate them overlooking the sea, thinking about how my father had visited 58 years before on his own hillwalking adventure.

During the long drive home the following day, I still carried the glow of Assynt as I sang along to my new favorite highland folk band.

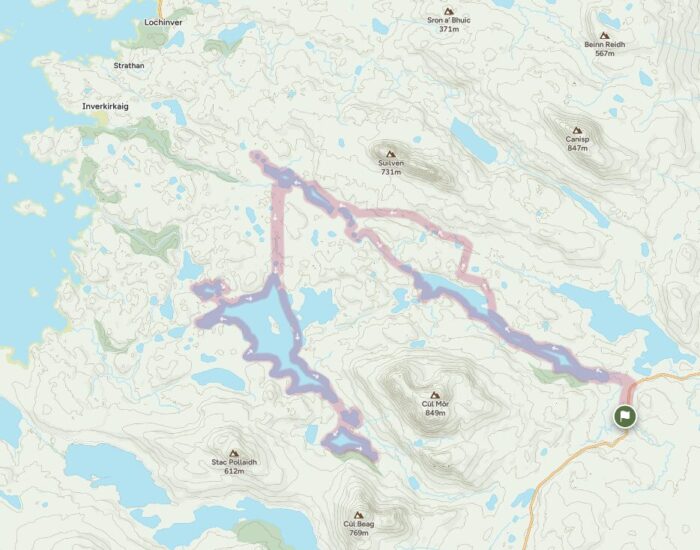

The route weaves through the heart of Assynt. Larger lochs are to the south, and out of the picture to the north. A longer packrafting journey could string together all of these inland lochs, sea lochs, and mountains over several weeks. Map: OS Maps