A French ultra-distance cyclist has been released from custody in Russia with a fine after almost two months in prison.

The Pogranichny District Court in Russia’s Far East found Sofiane Sehili guilty of illegally crossing the border from China. It imposed a fine of 50,000 roubles (around $615) and ordered his release from the jail where he’d been held since September 2.

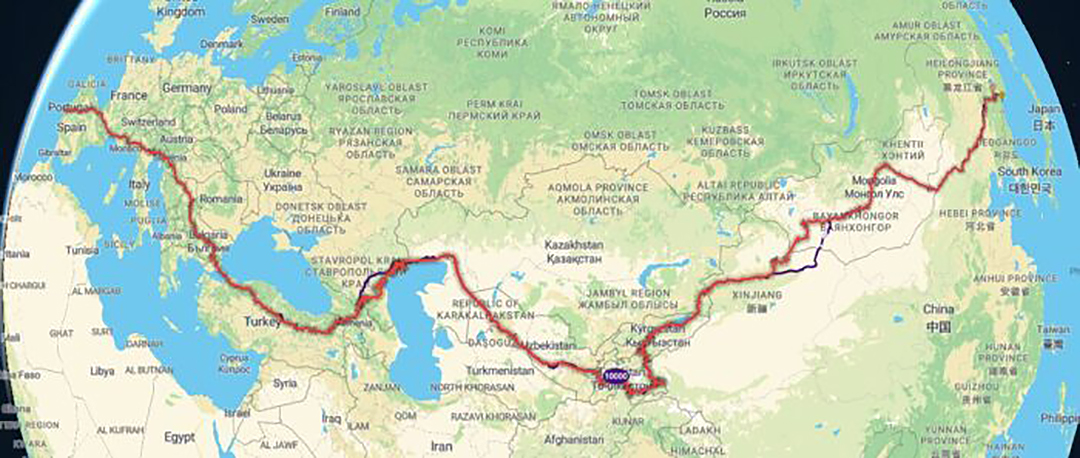

Sehili, 44, had been attempting to complete a 17,500km solo and self-supported ride from Lisbon, Portugal, to Vladivostok, Russia, aiming to become the fastest person to cross Europe and Asia by bicycle. He set out in early July, aiming to cycle through 17 countries in around two months.

As Sehili approached the final few days of travel, he tried to reenter Russia from China through a frontier post open only to train and bus traffic. Before China, his route in the east had taken him through Georgia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia, with several deviations into Russia en route.

Sehili’s GPS tracks from Portugal to China. Map: followmychallenge.com

A risky crossing

At a remote frontier post, Chinese officials told Sehili he could only cross by taking a 20km train. Refusing to do so, the Frenchman rode through rough woodland and along the railway line to reach the Russian border post on his bike.

Sahili presumably took this unorthodox route because the train journey would have ended his self-supported status and any record he would have claimed at the end. He was immediately arrested and accused of an illegal border crossing.

While trying to sneak across a border would land you in trouble in any country in the world, six weeks in jail — with no assurance that his detainment will end — is harsh. Also, he wasn’t trying to sneak across; he presented himself at the border and had an e-visa for Russia. It was just the wrong sort of border post.

Sehili behind bars. Photo: AFP

Record in sight

According to his GPS tracker, Sehili had covered 17,728km, averaging 280km per day, with just 179km remaining to Vladivostok. His elapsed time stood at 62 days, within striking distance of the existing Eurasia record of 64 days and two hours, set by Germany’s Jonas Deichmann in 2017 at a time when travel in Russia for Westerners was not as fraught with political consequences.

The central square in Vladivostok, Sehili’s end point if he had finished the journey. Photo: Shutterstock

A thriving hub for adventure

Before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the country and its network of Russian-operated expedition logistics were a thriving hub for adventure. Each winter, for example, sledders would head to Siberia to traverse frozen Lake Baikal.

Likewise, many aspiring North Pole skiers relied on the floating ice station Camp Barneo as their launch point for reaching the Pole. However, a combination of political tensions and changing ice conditions has kept Barneo closed since 2018.

Lake Baikal in better times. Photo: Ash Routen

Sehili’s release comes amid strained French-Russian relations and a rising number of Westerners detained in Russia. It’s not only political figures who have been affected; adventurers have also found themselves caught in the fallout.

In 2022, British adventurer Charlie Walker found that out in 2022, shortly after the war began, when he spent a month in a Russian prison for “conducting journalism while on a tourist visa” while on a manhauling expedition along the frozen Lena River. Reflecting on his experience, he noted, “I won’t be rushing back.”

A warning to other adventurers

Sehili’s arrest serves as a reminder that for most Western adventurers, Russian travel remains a gamble.

As well as potential bureaucratic issues, any traveler spending time there and contributing to the local economy risks being accused of supporting the war effort, making the ethics of pursuing adventure in Russia questionable.

One commenter on Sehili’s last Instagram post before his arrest wrote:

“The attempted record by Sofiane Sehili is an impressive human feat, but it raises important questions. The idea that sports can exist in a vacuum, detached from geopolitical realities, is a dangerous illusion, especially when Europe is under attack.

To celebrate a personal victory in a country currently waging war, while ignoring the context and the human cost, could be seen as deeply selfish. It’s a sad lesson that a desire for personal glory can blind us to the moral complexities of the world we live in. Sometimes, the universe has a way of reminding us that our actions and their consequences are interconnected, a concept some might call karma.”

In another country, Sehili might not have spent six weeks in jail for his unorthodox crossing, but in today’s Russia, such risks are an unavoidable reality for any outsider seeking adventure.