Tomorrow, January 23, Alex Honnold will attempt to climb a 508m Taipei skyscraper live on Netflix. No ropes — just him, a pair of climbing shoes, and a chalk bag. The stunt has focused attention on climbing like nothing since his Academy Award-winning Free Solo film. Even Saturday Night Live did a skit on it this week.

To set the stage, we revisit the crazy history of urban free soloing.

Buildering started as a sneaky university thing back in the early 1900s. Students scaled college roofs at night, without specialized gear. They were just young men seeking adventure and adrenaline on knobby Cambridge spires. Fast-forward to today, and we’re talking about 101-storey skyscrapers.

In 1899, Geoffrey Winthrop Young published The Roof Climber’s Guide to Trinity, providing instructions for scaling the college’s buildings. Young’s book was a kind of guidebook that detailed specific routes to the roofs of Trinity College buildings, including the library, the chapel, and the Great Gate.

The book is an “erudite parody” of the formal Alpine guides popular at the time. Young used mountaineering terminology to describe window ledges as “sloping parapets,” and rooftops as “impressive summits of the Great Court range,” blending humor with practical, illicit instructions.

The activity, known as night climbing or buildering, took place after dark to bypass the disapproving gaze of university authorities. Young’s book is the earliest-known literary work devoted to this sport.

The cover of the republication of the book, ‘The Night Climbers of Cambridge.’

Night climbing

George Mallory was an active night climber at Magdalene College, Cambridge (1900–1905), and even earlier at Winchester College, where he reportedly chimneyed up corners of buildings to impress visitors. This ties urban buildering to broader mountaineering culture, as many early rock climbers honed their skills on college architecture.

In 1937, Noel Symington, under the jaunty pen name “Whipplesnaith,” published The Night Climbers of Cambridge, a seminal work that codified the practice of climbing college structures. Symington used the pen name to protect himself and his fellow climbers from disciplinary action, which could include suspension or expulsion from the university.

The book offered details on climbing the various university and town buildings, including the spires and buttresses of King’s College Chapel. It even featured black-and-white photos of their exploits taken with “prehistoric photographic paraphernalia.”

Symington’s book became a cult classic, secretly passed among students. Young’s earlier, more limited guide for Trinity College is considered a precursor to Symington’s more comprehensive work. The activity was a mix of rebellion against strict curfews, a love of architecture, and an athletic pursuit.

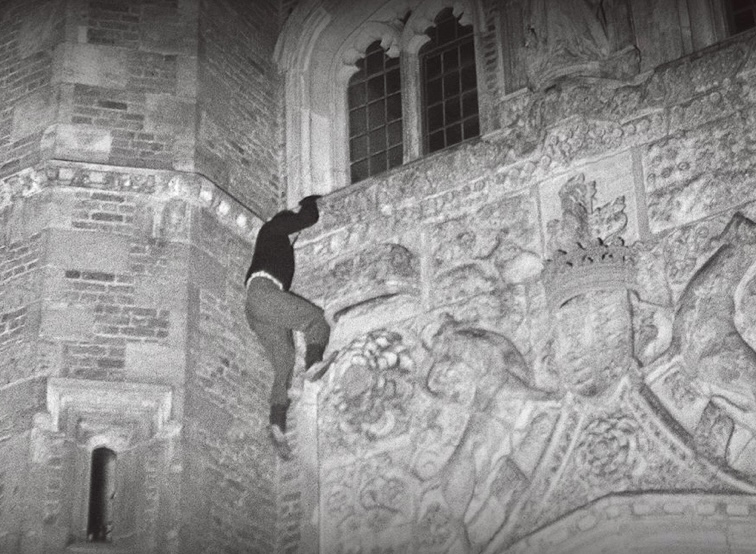

Night climbing on the roof of one of Cambridge University’s historic buildings, 1959. Photo: John Bulmer

Human flies

In North America, daredevils like Harry H. Gardiner of New York, the first of many known as the “Human Fly,” rose to prominence in the early 20th century, climbing skyscrapers to draw large crowds.

Gardiner began his career in 1905 and successfully climbed over 700 buildings, including the McAlpin Hotel in New York City and the Omaha World Herald building. For these feats, he typically wore ordinary street clothes and tennis shoes. He used no special equipment, ropes, or harness.

His stunts were major public spectacles, drawing massive crowds that sometimes caused traffic jams. (This was also the going over Niagara Falls in a barrel era.) These climbs were often publicity stunts sponsored by businesses, newspapers, or charitable causes, such as the sale of Victory bonds during World War I.

Rodman Law and “Steeplejack” Charles Miller were pioneering American daredevils who specialized in urban ascents at the turn of the 20th century.

Steeplejack Miller of Philadelphia was active between 1900 and 1910. He made his living performing ropeless climbs of buildings across major U.S. cities like New York, Chicago, and New Orleans, while a partner collected tips from the crowd. Miller famously scaled the Flatiron Building in New York to the ninth floor before police stopped him. (Many skyscraper climbers did their stunts illicitly, while Alex Honnold has obtained permission.)

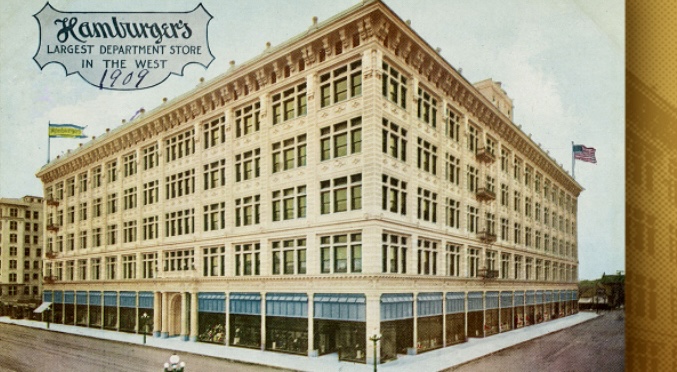

In 1910, Miller fell 18m while scaling the Hamburger Building in Los Angeles. He died in the hospital shortly afterward from his injuries.

A postcard of the Hamburger Building in 1909. Photo: Lapl.org

Buildering hits New York

Rodman Law, active from 1910–1917, and known as The Human Fly and The Human Bullet, was an American daredevil from New York and the brother of aviation pioneer Ruth Law. He was one of the first to combine urban climbing with other stunts.

Law climbed the Bankers Trust Building and the Flatiron Building in New York. Unlike pure climbers, he was also a pioneer in parachuting (BASE jumping) from the buildings he climbed. He even had himself shot out of a cannon to test early parachute designs. Law also starred in early silent films (like The Daredevil) that documented his stunts. He died in 1919 from tuberculosis.

George Gibson Polley of Virginia also billed himself as a Human Fly. He began in 1910, at age 12, by scaling a storefront in exchange for a free suit. He later climbed over 2,000 buildings across the U.S.

In January 1920, Polley attempted to climb the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan. While he aimed to summit the entire 57-story structure, he was intercepted by police after reaching the 30th floor for climbing without permission. Like other Human Flies, he too performed without safety gear. His stunts helped popularize buildering in New York City from 1915 to 1920.

Human Fly Harry Gardiner hanging from the 22nd floor of Hotel McAlpin on Broadway in 1922. Photo: Old Historical Pictures/Facebook

Hired stuntmen

Harry F. Young was a prominent American Human Fly and professional steeplejack who climbed hundreds of structures across the United States before his 1923 fatal fall from the Hotel Martinique in Midtown Manhattan. He belonged to the era where performers were hired to draw crowds.

His final climb was a $100 publicity stunt to promote Harold Lloyd’s film Safety Last! During his career, Young described himself on his business cards as “America’s unique and original steeplejack and stuntist,” promising to work in “impossible places to reach.” His death triggered the legal prohibition of urban climbing in major cities.

George Willig of New York climbed the World Trade Center South Tower in 1977. At the time of his historic 3.5-hour ascent of the South Tower, he was a 27-year-old toymaker and amateur climber living in Queens. He even practiced for the feat by scaling the Unisphere in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park a year prior.

Modern daredevils

In the spring of 1981, Dan Goodwin (a.k.a. “Spider-Dan”) famously climbed the Sears Tower (now Willis Tower) in Chicago on May 25 while dressed as Spider-Man, using suction cups and other aids. In November of the same year, Goodwin attempted to climb the John Hancock Center in Chicago, but had to abort the climb due to resistance from firefighters.

A few days later, he successfully climbed the Renaissance Tower in Dallas, Texas, while dressed as Spider-Man. Then he immediately returned to the Hancock Center and successfully climbed the 100-storey building, despite being sprayed with high-pressure hoses. In 1986, he climbed Toronto’s CN Tower twice in one day — a Guinness record, for some reason.

Alain Robert during an official climb in Abu Dhabi. ‘Climbing solo in front of such a crowd is no small thing,’ he posted on social media. Photo: Alain Robert

Alain Robert, the evergreen badass

If we’re talking modern urban soloing, Alain Robert is the guy. The French Spider-Man started out as a legitimate, super hardcore rock climber. Robert did his first 5.13d free solos back in 1991 — a free soloing degree of difficulty that Honnold admits he himself never attempted. Sponsors nudged him toward buildings in Chicago around 1994.

He’s knocked out over 200 towers, was arrested 170 times, and is still going strong in his 60s. He remains an absolute beast, despite lifelong vertigo and old injuries from brutal falls back in 1982. In 2024, at age 62, he pulled off another urban free solo in Manila.

Robert’s urban climbs include the Empire State Building, Petronas Towers, the Jin Mao Tower, and many others. Most of them were unauthorized and ropeless. However, for certain sanctioned climbs like the Burj Khalifa in 2011 and Taipei 101 in 2004, he used a harness to comply with local safety requirements. Buildings aside, Robert is one of the best free soloers in history with an incredible risk tolerance, climbing ropeless just one grade below his absolute limit.

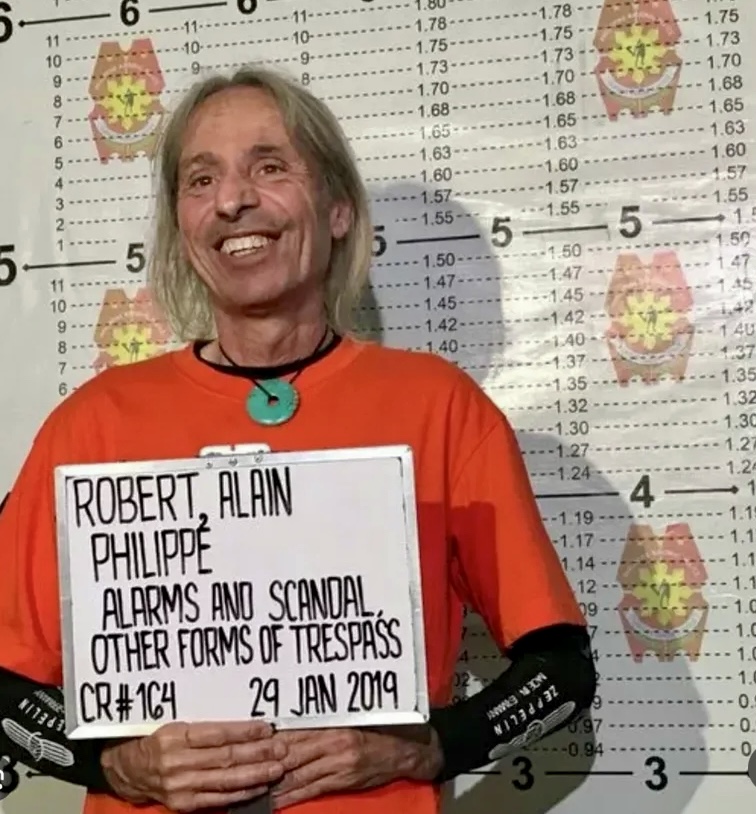

Alain Robert, during one of his 170 arrests for unauthorized urban free soloing. Photo: Alain Robert

Roofing for social media clicks

From around 2008, “roofing” gained popularity in Eastern Europe — especially in St. Petersburg, Russia, and Ukraine — where climbers shared footage from cranes and skyscrapers on social media. Roofing is a subgenre of urban exploration (urbex), focused on reaching the highest points of buildings and structures without safety equipment.

Ukrainian climber Mustang Wanted (born Pavlo Ushivets) became the movement’s most iconic figure. He gained notoriety in the early 2010s for sharing extreme point-of-view footage of himself hanging from cranes and skyscrapers by one hand.

The popularity of this movement coincided with the rise of social media and video-sharing platforms like YouTube and Facebook, which allowed climbers to post terrifying POV footage that frequently went viral. Unlike historical Human Flies, who often climbed for commercial promotion, these Eastern European roofers focused on artistic and rebellious expression, often performing acrobatic stunts on bridges and antennas at extreme heights.

Modern climbers like George King, who climbed London’s The Shard in 2019, continue the tradition of high-profile, often illegal urban ascents that result in fines and other penalties.

Leo Urban, the French Tarzan, was a prolific contemporary urban free soloist and YouTuber, also known for his parkour and outdoor climbing. In March 2022, he and Alexis Landot free soloed the 210m Montparnasse Tower in Paris in 52 minutes to raise funds for Ukraine. The ropeless climb was graded at about 5.10a–5.10b, and they had practiced extensively on lower sections. This so-called French Tarzan blends urban climbing with barefoot parkour elements and shares POV footage online.

Seb Bouin and Alain Robert free soloing on a Paris skyscraper. Photo: Jan Virt

More free soloists

Alexis Landot often collaborates with Leo Urban (as in the 2022 Montparnasse ascent). He’s a “free urban solo climber,” known for ropeless high-rise ascents, sometimes for charitable causes. He has teamed up with Alain Robert on occasion and is active in the French urban climbing scene, posting videos of extreme building solos.

Seb Bouin is one of the world’s top sport climbers (multiple 5.15 first ascents/repeats). In October 2024, he free soloed a 183m building in Paris alongside Robert. While Bouin is primarily a rock climber, like Honnold, elite athletes occasionally venture into urban free soloing.

Maison DesChamps bills himself as an American “Pro-Life Spider-Man.” In 2022, he free soloed the 326m Salesforce Tower in San Francisco, one of the tallest in the U.S. at about 326m. He was arrested afterward.

Justin Casquejo (LiveJN) is an American rooftopper and free solo climber, active since 2014. Known for sneaking to the top of the under-construction One World Trade Center (541m) in 2014, his wasn’t a full free solo (he took an elevator partway up and then climbed the stairs and ladder to reach the antenna), but it was a high-profile urban ascent. He has ascended other structures like the Weehawken Water Tower and shares extreme POV content.

Adam Ondra briefly did a commercial facade climb on the Filadelfie skyscraper in Prague in 2024, but it wasn’t a full free solo. It was more of a sponsored stunt blending his rock-climbing prowess with urban elements.

Maison DesChamps free soloing Salesforce Tower. Photo: farandwide.com

Urban free solo fatalities

Precise fatality counts for urban free soloing, specifically in the case of towers and skyscrapers, aren’t noted in a single official register, as many incidents are unrecorded or classified broadly as falls from a height. However, data from extreme sports and notable incidents provide a clear picture of the risks.

While many famous pioneers like Robert and Goodwin are still active, several prominent figures in the roofing and buildering movement have perished during their ascents.

In 2013, Pavel Kashin, a Russian freerunning athlete (urban acrobat), fell from the edge of a 16-story building while performing a backflip on the ledge.

In 2015, Connor Cummings fell from the Four Seasons Hotel in New York City while attempting to climb it. Cummings slipped while climbing scaffolding on the outside of the building and fell nine stories onto a 43rd-floor catwalk.

In 2017, Wu Yongning, a high-profile Chinese roofer, fell to his death from the 62-story Huayuan International Center while performing a stunt for a social media challenge.

In 2023, French climber Remi Lucidi, known as Remi Enigma, fell from the 68th floor of the Tregunter Tower in Hong Kong. Investigation of his camera found footage of him on other high-rise structures, and he was reportedly last seen knocking on a penthouse window, possibly seeking help.

Remi Lucidi. Photo: Instagram

Factors contributing to deaths

Like natural rock, urban surfaces can have unexpected factors such as loose decorative panels, wet metal, or sudden high-altitude wind gusts.

A growing number of fatalities involve non-high-profile climbers attempting stunts for social media without the years of technical training required by elite soloists.

Legal issues count too, because most urban climbs are unauthorized, and free soloists often rush to avoid security, which increases the likelihood of a fatal error.

Taipei 101. Photo: Wikipedia

Alain Robert’s climb of Taipei 101

Taipei 101 is located in Taiwan. The 508m building has 101 floors above ground and five basement levels. It was officially classified as the world’s tallest building when it opened in 2004, until it was surpassed by the Burj Khalifa in 2010. Now, it is the 11th-tallest building in the world.

Robert became the first person to successfully climb its exterior on Christmas Day, 2004. His ascent wasn’t a free solo, as he used a top-rope and harness — a safety requirement imposed by the Taiwanese government. It sanctioned the climb as a public relations event to celebrate the new tower’s status as the world’s tallest building. Robert also jumared a short section near the summit.

Robert primarily used his bare hands and feet to ascend the building’s metal and glass facade. He paused every eight floors — the equivalent of about one pitch — to rest. Heavy rain and strong winds hampered the climb, as did the greasy construction materials and vinyl on the unfinished facade.

The adverse conditions lengthened the climb into nearly four hours, almost double his original estimate. Honnold expects to finish in about an hour and a half.

Alex Honnold is already in Taiwan. Today, January 22, he practiced the moves before his free solo on January 23 (January 24 in Taiwan). Photo: Focus Taiwan/Instagram

Alex Honnold on Taipei 101

Primarily known for natural rock faces like El Capitan, Alex Honnold aims to apply his skills to urban structures. In 2018, he attempted a ropeless climb of the Urby in Jersey City, but bailed halfway at the 24th floor due to wet conditions. A maintenance worker eventually opened a window to let him in.

Honnold’s Taipei 101 free solo will stream live on Netflix on January 23, beginning at 8 pm ET; January 24 at 2 am CET; and 9 am in Taiwan.

Honnold has diligently practiced on the building using ropes as preparation. No one has successfully completed a free solo of the entire exterior of Taipei 101.