Jacob Pepper, 41, completed a 9,334km thru-hike of the Eastern Continental Trail (ECT) late last month. Setting out from Key West, Florida, on January 1, the American reached Hay Cove in Newfoundland, Canada, on September 30. Over 273 days, Pepper spent 250 days on the trail, climbing a total of 231,495m in elevation.

Having previously worked in a corporate law firm after college, Pepper turned to thru-hiking after seasonal work in the charter boat industry and a stint working on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Since starting out on the Appalachian Trail in 2020, he has covered more than 26,000km on foot in the past five years, completing iconic routes such as the Pacific Crest Trail, Colorado Trail, Florida Trail, Arizona Trail, and the Continental Divide Trail. But the Eastern Continental Trail is the longest and most rarely done of them all.

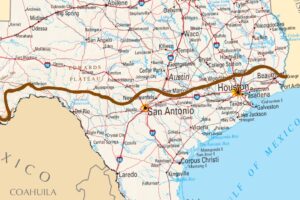

The Eastern Continental Trail

“The ECT had also been in the back of my mind since I did the Appalachian Trail the first time, because it’s part of it,” he told ExplorersWeb. “I met some kids that year who were doing it, and I was like, ‘What are you talking about? You’re going all the way up the east coast of North America, and it’s over 5,000 miles?’”

The Eastern Continental Trail Route Map. Map: Wikipedia

The mammoth trail is a link-up of seven already established trails, including the well-known Appalachian Trail, and the less-publicized International Appalachian Trail, which connects Mount Katahdin in Maine to the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec.

- Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail — 174km

- Florida Trail — 2,268km

- Alabama Road Walk — 322km

- Pinhoti Trail — 565km

- Benton Mackaye Trail — 97–129km

- Appalachian Trail — 3,535km

- International Appalachian Trail — 2,543km

International Appalachian Trail sign in Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

The ECT has no official record of how many hikers have completed it. In 2024, Madison Blagden suggested she was only the second woman and ninth person overall to finish the route. Endpoints vary, with some hikers finishing at Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula and others continuing, like Pepper, to Newfoundland. One website tracking voluntary submissions lists 40 finishers, beginning with John Brinda in 1997.

The knife edge trail on Mount Katahdin on the northern section of the Appalachian Trail. Photo: Jacob Pepper

Snow in the subtropics

Pepper experienced nearly every North American climate, from subtropical heat to progressively wetter and cooler conditions. His time on the trail featured unpredictable weather, particularly at the start.

“You’re starting in the Florida Keys, which is like, subtropical. It’s beautiful. When you hit the trail, you’re wearing shorts, you’re getting sunburn, you’re in the islands, it’s like, ‘Man, this is going to be easy’.”

The Florida section is also home to plenty of swamps. Photo: Jacob Pepper

That early comfort didn’t last, though.

“It snowed in Florida, which is just unheard of,” Pepper explained.

From there, he faced freezing rain, frequent thunderstorms, and long stretches of wet and cold conditions were common in the southern states.

His trail name became “Bad Timing” because Pepper had picked a year to hike the ECT when the thunderstorms and rain just kept coming.

Recurring health issues

Despite suffering a serious neck injury in a 2022 car crash that left him at risk of paralysis with any future whiplash, he has since put many thousands of kilometers on his legs. Remarkably, it wasn’t the old injury that troubled him on the Eastern Continental Trail, but a mysterious gastrointestinal illness that cost him nine days on the hike.

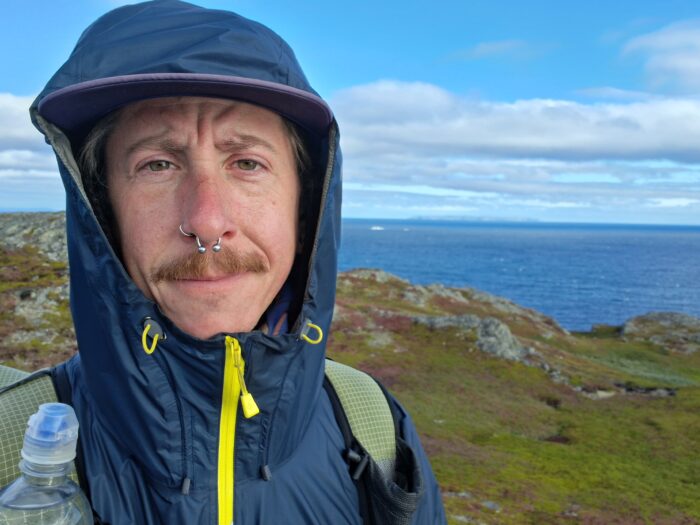

Photo: Jacob Pepper

“I passed out in broad daylight, right next to the trail, for eight hours,” Pepper said of one occasion of the mystery illness.

“It felt like somebody was grabbing my intestines and squeezing them. You know, there was this crazy cramping, inflammation, bowel inflammation going on, and it was terrifying. I didn’t know if I was going to wake up in the hospital. I didn’t know if I was going to be able to finish my hike.”

Six pairs of shoes

Over the 250 days of hiking, Pepper averaged a whopping 37km a day, and over 50km on some days. Over time, he has developed a more efficient walking gait, he says, that reduces the burden on his feet. As a result, he wore through only six pairs of trail shoes, stretching them out to nearly 1,600km per pair.

Like many thru-hikers, he ruthlessly edited his pack weight, carrying just around 4kg without food and water, and resupplying along the way. With a neck injury to manage, traveling ultralight was particularly important.

Photo: Jacob Pepper

“Typically, there’s a town within reach of the trail every 150 kilometers max. On the Appalachian Trail, it’s almost like every other day you can access something,” he explained.

Sticking to ultralight principles, Pepper cold-soaked his meals, foregoing a stove and hot food. Not surprisingly, he spent hundreds of days eating a trail favorite – mashed potatoes.

Pepper had to make several boat crossings — for example, from mainland Nova Scotia to the island of Newfoundland, where he finished.

Hiking mainly solo

On previous thru-hikes, Pepper had spent long sections bonding with other trail goers, soaking up the camaraderie that only time on the trail can foster.

The biggest takeaway from through hiking is the depth and intensity of real human connection that you can make in that context. When you are broken open, totally exposed to reality, and you’re sharing that survival with other people, it’s hyper bonding. And I’ve always said that, thru-hiking is an accelerated existence. You live an entire lifetime in the course of a trail. You are born, you live, and you die…When you share that with other people, you are bonded with them for life.

Pepper chose to hike solo on the ECT, though, joining others for only a day or two. He shared one 50km stretch of the Appalachian Trail with another hiker, who remained about 160km behind for the rest of the journey. The two stayed in regular contact via smartphone, maintaining a sense of connection while respecting each other’s independence — what thru-hikers call “hiking your own hike.”

On the Newfoundland section of the ECT. Photo: Jacob Pepper

Fulfilment through hiking

For Pepper, the highlight of the Eastern Continental Trail came not at the finish line, but in a quiet moment of reflection in Quebec. After enduring some of the toughest days of the hike, he camped below Mont Matawees and took time to appreciate where he was.

“I parked it at this gorgeous overlook for a full hour and just stared out at the St. Lawrence River,” he said. “It was really hitting me that I was actually accomplishing my goal, and that this beautiful moment was my life.”

The spot where Pepper soaked it all in. Photo: Jacob Pepper

That pause, he explained, captured the essence of why he hikes. “It’s rare on these long hikes that I have the opportunity to really sit, meditate, reflect, and appreciate the moment in full,” Pepper said.

“I’ve hiked 16,500 miles [including the ECT] so that I can feel fulfilled in this life, in this body, in this reality, and it’s those moments that make it worth it.”