For centuries, the Yangtze porpoise was a common sight on the river it is named after. Now, the freshwater mammal is critically endangered, rarely sighted, and only found in a tiny proportion of the huge waterway that winds from the Tibetan Plateau to the East China Sea. To track the species’ decline, researchers have turned to an unusual source— ancient Chinese poetry.

Researchers analyzed 724 ancient Chinese poems that referenced the Yangtze porpoise. Some date back to the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). Penned by scholars, emperors, and poets who often traveled along the Yangtze, the poems provide vivid accounts of the porpoise’s presence and behavior.

“Our work fills the gap between the super long-term information we get from fossils and DNA and the recent population surveys,” said Zhigang Mei, co-author of the new study. “It really shows how powerful it can be to combine art and biodiversity conservation.”

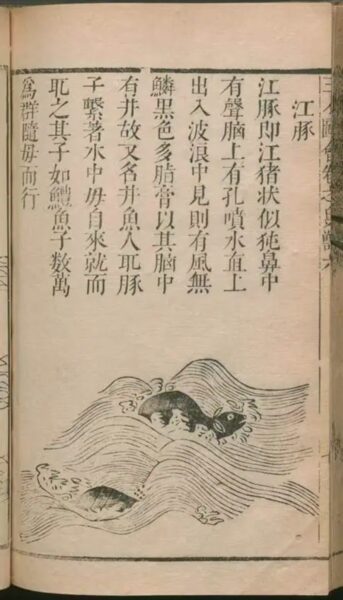

A Ming Dynasty woodblock illustration from a 49-volume book of poems on birds and animals, compiled by Wang Qi (1573–1620). Credit: Wang Qi

Harming the porpoise was bad luck

The Yangtze finless porpoise holds an important place in Chinese folklore. Mei remembers the elders in his community speaking of them as spirits, believing they could predict weather changes and good fishing. Harming the creature was considered bad luck. This is perhaps why they featured so heavily in ancient poetry.

To ensure accuracy in the poem’s content, the researchers cross-referenced the information in the poem with what they knew about that author’s life. They identified where each poet lived and traveled to ensure that it matched the information within their poems. This approach allowed them to extract reliable ecological data from the verses.

Using the poems with historical records, they mapped the porpoise’s distribution across different dynasties. Poems from the Qing dynasty referenced the porpoises 477 times, whereas they appeared slightly less in earlier periods.

Despite this, there was a clear pattern. Over time, a sharp decline in porpoise sightings has occurred. Tributaries and lakes associated with the river had a 91% decrease; the main river channel had one-third fewer. Overall, the findings reveal a staggering 65% reduction in the porpoise’s habitat over the last 1,400 years.

Xiling Gorge on the Yangtze River. Photo: Shutterstock

Causes of decline

Poets like Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty often described the porpoise’s playful antics, especially its tendency to leap from the water in stormy weather.

“Compared to fish, Yangtze finless porpoises are pretty big, and they’re active on the surface of the water, especially before thunderstorms when they’re really chasing after fish and jumping around,” explained Mei. “This amazing sight was hard for poets to ignore.”

Since the 1950s, new dams have made huge sections of the river inaccessible to the porpoises. Pollution and fishing have also affected the porpoise populations.

With fewer than 1,800 freshwater porpoises left in the river, conservationists are worried they will follow the same path to extinction as their cousins, the Yangtze River dolphin.

“Protecting nature isn’t just the responsibility of modern science; it’s also deeply connected to our culture and history,” said Mei in a statement. “Poetry can really spark an emotional connection, making people realize the harmony and respect we should have between people and nature.