Bracketed by two ice ages, the Cambrian period produced some strange creatures. Among them were seafloor-dwelling predatory sandworms. Armed with a nasty collection of teeth and curved spines, they were seemingly straight out of the movie Dune, except they were only an inch or two long.

Now, a team of scientists has discovered a new species of these Selkirkia worms that existed 25 million years later than expected.

A conveyor belt of fangs and teeth

Selkirkia worms were a common predator roughly 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period.

“If you were a small invertebrate coming across them, it would have been your worst nightmare,” study co-author Karma Nanglu told the New York Times. “It’s like being engulfed by a conveyor belt of fangs and teeth.”

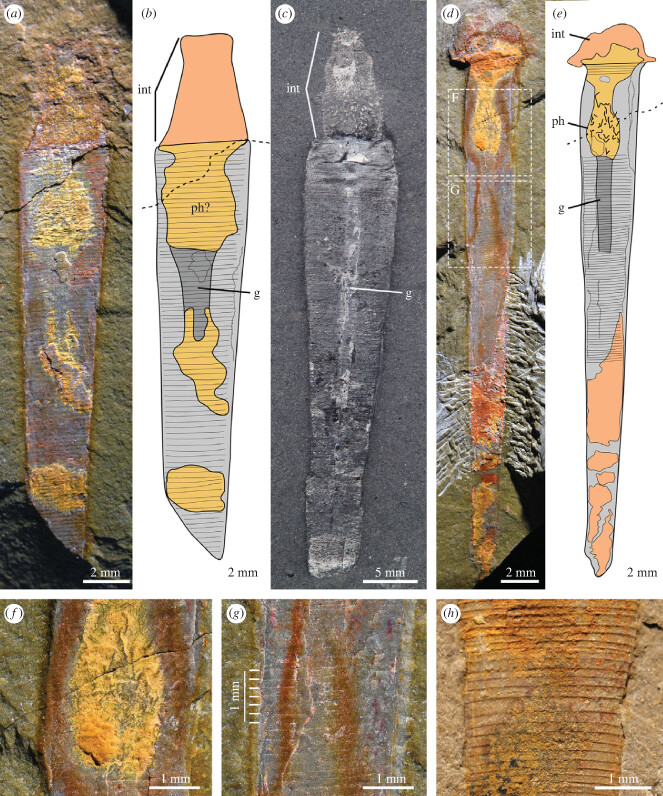

Fossils and diagrams of the new worm species. Photo: Karma Nanglu and Javier Ortega-Hernandez

The worms formed cone-shaped tubes around their bodies from material secreted by the worm. The tubes were likely defensive but may have become a hindrance when free-swimming predators emerged at the end of the Cambrian Explosion. It forced the worms to either evolve or go extinct.

A true survivor

The worms disappeared from the fossil record until Nanglu and his team stumbled on some interesting fossils stored in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. While examining samples extracted from Morocco’s Fezouata Formation, they spotted some fossils that looked extremely similar to Selkirkia worms, only 25 million years out of place.

After analyzing the fossils, they determined this was a new species of Selkirkia worm. The team has named the species tsering, from the Tibetan for “long life.” The discovery shows that these predatory worms survived the end of the Cambrian Explosion and well into the early Ordovician period. They were finally outcompeted in an increasingly diverse ocean ecosystem.