There are only five species of rhinoceros alive today, and most are very endangered. The prehistoric past, however, held over fifty species over many different environments. A new study from The Canadian Museum of Nature describes a new species of ancient rhinoceros. Unlike its more familiar living relatives, Epiaceratherium itjilik had no horn, and lived in the High Arctic 23 million years ago.

This discovery introduces a unique new species and a deeper insight into the ancient rhino lineage. But it also has a broader significance, altering our understanding of neglected land bridges in the North Atlantic.

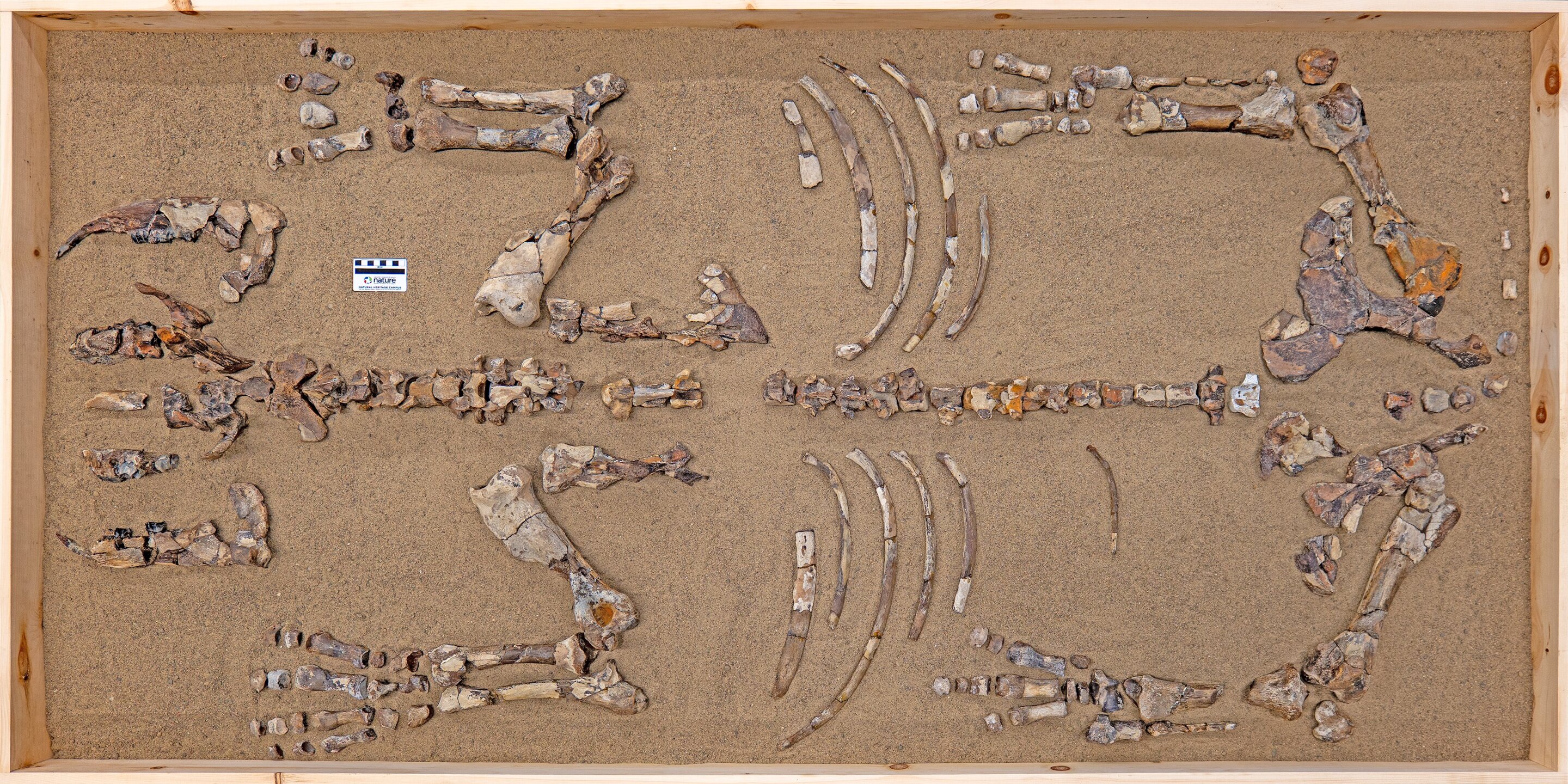

For a 23-million-year-old dead rhino, it looks fantastic. Photo: Pierre Poirier/Canadian Museum of Nature

Meet Epiaceratherium itjilik

On Devon Island, the world’s largest uninhabited island, a team from the Canadian Museum of Nature discovered a well-preserved and nearly complete fossilized rhino. This is the furthest north that any rhino has ever been found. The remains were in remarkable condition. Over 80% of the skeleton was intact, and the bones themselves were still three-dimensional.

The well-preserved remains allowed researchers, led by Dr. Danielle Fraser, to compare the High Arctic rhino with its Eurasian relatives. The teeth, jaw, finger bones and femur showed distinct differences, marking this as a new species.

Since the discovery occurred in Inuit territory, the researchers consulted elders from Canada’s northernmost community of Grise Fiord. After learning a bit about the animal, Jarloo Kiguktak, the former mayor, suggested the name itjilik. The name comes from an Inuktitut word meaning “frosty.”

Epiaceratherium itjilik was relatively small and stocky, without a horn, and related most closely to four other hornless Epiaceratherium species. The reconstructed genetic tree showed that our Epiaceratherium diverged from the rest in the late Eocene, 34 and 40 million years ago. So how did it get to the Arctic?

Jarloo Kiguktak, the former mayor of Grise Fiord, named the new species. He was also part of the team’s earlier expeditions to Devon Island. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Ice-hopping megafauna?

Like the more famous Bering Land Bridge, a series of land bridges in the North Atlantic once connected the Canadian Arctic with Iceland, Greenland, and continental Europe. Animals used these bridges to move back and forth, but according to conventional wisdom, they were not used much after the late Eocene, about 54 million years ago.

Our new friend, Epiaceratherium itjilik, overturns that supposition. They likely crossed the North Atlantic Land Bridge as many as 20 million years after the bridge’s previous “end date” estimate.

It’s difficult to study long-drowned land bridges. They are, after all, deep below the waters of the North Atlantic. But the current geological science suggests that this causeway was a low stretch of land interrupted by thin bands of water. Seasonally, ice could cover those waterways, allowing animals, like the ancestors of Epiaceratherium itjilik, to cross in the same way that contemporary Arctic animals like caribou and muskoxen now cross from island to island over frozen ocean.