In spring 2021, a record 67 climbers reached the summit of Annapurna. The record required a huge logistical operation involving aerial resupplies to Camp 4, heavy use of supplementary O2, and a good deal of luck with the weather and conditions. Many summiters then caught a helicopter ride to Dhaulagiri, to go for a second summit.

Some in the climbing community were critical: “Do they really think they climbed Annapurna? Definitely not my Annapurna,” Jonatan Garcia said.

We caught up with Garcia to discuss his experiences on the dangerous 8,091m giant.

Garcia’s Annapurna – 2017

“There are many Annapurnas, as many as different experiences,” the young Basque climber told ExplorersWeb, his five-month-old baby boy playing by his side. “When I went there, I only had a previous attempt on Broad Peak as a Himalayan experience. I just wanted to climb with Alberto [Zerain],” he says.

With nine 8,000’ers under his belt, Zerain is a role model for many young Spanish climbers. For Zerain, Annapurna was a logical next step, but neither he nor Garcia had been on the mountain before.

Alberto Zerain (left) and Jonatan Garcia on Annapurna, 2017. Photo: Jonatan García

Chilean climbers Juan Pablo Mohr and Sebastian Rojas were also on the mountain in 2017. They described Annapurna as the “essence of adventure”. It was their first Himalayan experience and a superb gateway to mountaineering as a profession. They showed up in Base Camp determined to climb a new variation of the route across the highly exposed face between Camp 2 and Camp 3.

Finally, there was the veteran Italian couple, Nives Meroi and Romano Benet, on their third attempt on Annapurna and the last hurdle in their 20-year 14x 8000’ers quest. In 2017, less than 50 people had ever summited Annapurna. This, despite its distinction as the first 8,000m peak ever summited, by Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal in 1950.

“When we met in Base Camp, we immediately knew we would have to cooperate and join forces,” Garcia recalls. There were no commercial teams on the mountain (a Sherpa guide and his Norwegian client abandoned before setting foot on the mountain), no ropes on the normal route, and no supplementary O2.

Chileans Juan Pablo Mohr and Sebastian Rojas at Annapurna Base Camp. Photo: Chilean Annapurna Expedition

The approach trek

The Annapurna region is one of Nepal’s most popular trekking areas. However, the famous Annapurna Circuit passes the south side of the mountain, while the normal route to Base Camp goes up to its north side, with much less attractive surroundings.

“Honestly, unless you really want to avoid airlifts and keep it pure, I recommend acclimatizing somewhere else and then getting an airlift to Base Camp,” Garcia said.

The trek from Tatopani is uncomfortable, with no lodges on the way. Instead of heading up a valley, it crosses cols and has long traverses on steep mountain flanks, often exposed to unstable weather. This may result in problems with the porters, who can refuse to continue if snow blocks the higher passes.

Alberto Zerain near Base Camp. Photo: Jonatan Garcia

Base Camp (4,000m)

Garcia describes Base Camp as one of the best he has enjoyed in the Himalaya. “I called it ‘the beach’ because the ground was grassy or formed by small pebbles, like a beach,” he said. “It is warm, lower than other Base Camps, and completely safe. Even when it snows, the ground dries up so quickly.”

Left to right: Romano Benet, Nives Meroi, Jonatan Garcia, and Alberto Zerain in Base Camp. Photo: Alberto Zerain

Base Camp (4,000m) to Camp 1 (5,000m)

From Base Camp, the early going is on rock and sand, which eventually traverses to the right to avoid a big rock.

“That section is a bit exposed to rockfall but it soon goes up again to what’s called Crampon Point,” says Garcia. “Then you gain altitude up a mild hill-like walk that is pretty safe. However, conditions change from day to day. In dry conditions, you can get to Camp 1 in sneakers. In general, Annapurna is a warm 8,000’er.”

Camp 1 is typically used only for a first rotation and to carry loads. Most climbers skip it on their following trips up, including on the summit push.

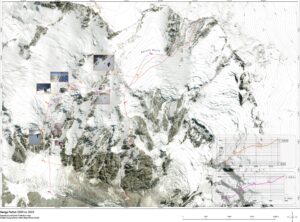

Annapurna’s normal route follows the northeast ridge, with some possible variations. Photo: Caingram

Camp 1 (5,000m) to Camp 2 (5,700m)

“The way goes up a huge plateau filled with crevasses that you need to avoid until the upper end,” Garcia said. “It feels like walking up a wide, white blanket of snow. You go over small bumps and orienteer through the crevasses, until you get to the base of Annapurna’s proper face.”

There, you set up Camp 2.

“Camp 2 is wide, on snow, but not so safe,” Garcia explained. “This is why, in my opinion, Annapurna is not good for acclimatization. Even Camp 2 is not a great place to spend too long.”

Photo: Alberto Zerain

Camp 2 (5,700m) to Camp 3 (6,600m)

Undoubtedly, the section between Camp 2 and Camp 3 is the crux of the climb.

“I felt like being in Pamplona, about to start running in front of San Fermin’s bulls! You take a deep breath and wait for the gates to open. The route sneaks, on rough terrain, right below the seracs above you. Constantly, chunks of ice fall and they can trigger avalanches.

“Experienced Sherpas know exactly where the less dangerous places are,” Garcia says. “We were not so knowledgeable, so we navigated as best we could.”

Garcia in snow up to his armpits on Annapurna. Photo: Alberto Zerain

It was between Camp 2 and Camp 3 that the six-person climbing group separated. Mohr and Rojas climbed a line to the left of the others, up a series of ice “fingers”. The Italians wanted to follow the original French route, while Zerain and Garcia thought that the German route would be safer. Their problem was that they had no way to check conditions until they actually got into the maze of seracs and crevasses.

The Dutch Rib route in blue, compared to the classic French route in red. Photo: Lindsay Griffith for the BMC

“By a sheer coincidence, Simone Moro happened to be flying over the area, saw us, and was kind enough to warn us [through Meroi and Benet] that we should change our plans. There was a huge crevasse above us that we couldn’t see,” Garcia said.

The (French) route as marked by Alberto Zerain at the end of the expedition.

So Meroi, Benet, Garcia, and Zerain all took the French route on their second attempt.

“We had to break trail in deep fresh snow. Our progress was so slow that night eventually fell and we were forced to pitch the tent at 6,200m, completely exhausted and in very exposed terrain.”

Only the following day did the four climbers manage to reach the upper area and a small ledge where they could place Camp 3.

“I remember Camp 3 was very uncomfortable, steep and narrow, with a crevasse very close. But it was safe, which was a relief,” Garcia said. “There was just room for our three tents. (We met the Chileans there.) Thinking about it, I fail to comprehend how the Sherpas put so many tents there for the bigger teams.”

German route variation

Another Basque climber, Juan Oiarzabal, has climbed Annapurna twice (among his whopping 26 8,000m summits). He first topped out in 1999 via the original French Route (Herzog, Lachenal, 1950). Then in 2010, he climbed via the German route. He shared his memories of the German route between Camp 2 and Camp 3 with ExplorersWeb.

Oiarzabal agrees that the most dangerous, avalanche-prone zone is between Camp 2 and Camp 3. Here the route crosses a huge plateau toward the face, right below the overhanging seracs along the so-called ‘Sickle’.

“That is hazardous because of serac fall,” Oiarzabal said. “However, the most common danger comes next, as one gets closer to the wall and heads toward a characteristic cone-shaped couloir, with a great serac on top. This serac is usually loaded with snow and pieces of it break off and fall from time to time.”

The German route on Annapurna’s north side. Photo: Ferran Latorre

As pieces of the serac fall down the cone, they trigger big, impressive, yet not so lethal, powder-snow avalanches.

“It looks like the whole mountain is falling on you,” Oiarzabal explained. “When we were on the plateau, sooner or later we would have to run left or right and try to protect ourselves. We knew most of it was snowdrift, but there were always chunks of ice falling with the snow.”

The Dutch Rib variation on Annapurna varies slightly on some topos. Photo: Tunc Findik

Arriving at the bergschrund at the base of the wall, the route climbs up and left, atop a spur. This gets climbers out of the reach of the powder snow avalanches. From the spur, the route continues up some of the most technical sections of the route.

“There are 45-55º steep ramps, with some short sections of 70º,” says Oiarzabal. “These require all of your stamina to overcome and reach Camp 3.”

Camp 3 (6,600m) to Camp 4 (7,000)

The Italian and Spanish climbers high on Annapurna. Photo: Alberto Zerain

“This section is short and straightforward, up snow ramps without big exposure from falling seracs. But there is the possibility of avalanches if loaded with fresh snow, as they have the perfect steepness to let avalanches go,” Garcia said. “It is only 400 vertical metres but not so direct. You need to climb to the left, navigating among seracs and crevasses.”

Again, Garcia recalls the hard work breaking trail with such a small group, but they were rewarded with a wide, safe Camp 4. “At 7,000m, it is low enough for a good sleep. I was able to rest peacefully, which was essential before the summit push.”

Summit day (8,091m)

“On May 11, we set off from Camp 4 at midnight sharp, to the best weather day we had had in the entire climb,” Garcia recalls.

The climb involved gaining 1,000 vertical metres. From Camp 4, the route follows obvious, easy ramps, then mounts a rib to the right. The rib can be rocky or mixed terrain, if wind-swept. Eventually, you get to the summit ridge.

“Then,” says Garcia, “you advance on mid-steep terrain, with the south side of the mountain on your left and the north side to your right. It took us some 15 to 20 minutes to the summit. This section was safe enough for us not to use ropes. Safe, of course, unless you slip and fall all the way down to Camp 2!”

It was slow-going and they counted their steps.

“We progressed at 100m per hour, which is good for a no-O2 climb, and summited at 10 am,” he said.

Jonatan Garcia on the summit of Annapurna, May 7, 2017. Photo: Alberto Zerain

French or German summit options

Juan Oiarzabal noted that there are some differences between the classic French route and the German line:

“From Camp 4 to the summit, the route goes along the obvious passage for a while, until right below the summit ridge. Once there, there are two options: Follow the German route or change to the original French route. Both involve long climbs up a slope averaging 40º to 45º.

He continued:

“If you take the original French route, you need to traverse horizontally to 7,800m, to get to the upper sections of the original route. At first, it is okay, but on the upper slopes, the climb gets rather technical and exposed. Or, you can follow the German route to the col, between the main summit and the eastern summit, then take the summit ridge to the main summit. This is less technical but longer.”

The descent

“I have this feeling, that if you respect the mountain, the mountain eventually rewards you,” Garcia explained. “After a whole month of unstable weather and five thwarted attempts to go further than Camp 2, on May 7 we launched another summit bid. On May 11 we were rewarded with a bluebird summit day, sunny and windless. It was possibly the easiest part! The descent was a completely different story…”

Climbers descend from Annapurna’s summit, down avalanche-prone slopes, in worsening weather. Photo: Chilean Expedition

“From the summit, we returned to Camp 4 for the night. Conditions were perfect,” Garcia recalled. “But the following day, we lived the most dangerous moments: a nerve-wracking descent from Camp 4 to Camp 2 as a storm broke and in avalanche conditions. We only stopped for some rest and relief when we reached Camp 2, where we stopped for the night.”

Fortunately, the team made it back to Base Camp on May 13.

Back in Base Camp

They all had reason to celebrate. Meroi and Benet had finally completed their 14 8,000’ers, the Chileans had opened their variation route, and Garcia had experienced what he believed Himalayan climbing should be: “A special expedition, pure, genuine.”

Mohr and Rojas’ Annapurna adventure was filmed and turned into a documentary, with some stunning footage. You can watch it below (in Spanish).

Unfortunately, Alberto Zerain barely had time to enjoy his success. He disappeared one month later while attempting the highly difficult Mazeno Ridge on Nanga Parbat. Juan Pablo Mohr continued his promising climbing career but he perished in January 2021 on Winter K2.

Garcia keeps climbing, both in the Himalaya and in the Pyrenees, where he lives. In 2021, he experienced a highly commercialized (and COVID-stricken) Dhaulagiri which turned him to lower but lonelier mountains. Last month, he attempted Gangapurna with Topo Mena.