The second half of 2022 has not been good to Grace Tseng of Taiwan. First, there were the many questions raised about her speed record claim on Manaslu last fall. Now, new doubts have arisen about her summit of Kangchenjunga in the fall of 2021.

An article co-authored by Hungarian journalist Laszlo Pinter and ExWeb’s own KrisAnnapurna on Mozgasvilag.hu analyzes Grace Tseng’s summit pictures and videos. Most of her visual record lacks the references of surrounding mountains, the article points out.

Some of the footage shot by her Sherpa team during the summit push even suggests that they deviated from the main route shortly after Camp 4. They may have ended up somewhere on Kangchenjunga’s summit ridge, far from the real summit.

More voices

Here, we’ll try to further the story, which is well worth a read, by adding other points of view. This includes Grace Tseng herself and members of her Kangchenjunga team. We have also contacted the experts at 8000ers.com and even the climbers who first stepped on the mountain after Tseng, five months later.

Some suggest that Tseng’s Sherpas innocently mistook the way up the peak’s confusing upper section. They may have ended up at a point on the ridge away from the highest point.

This would not be the first time that the tricky upper headwall of Kangchenjunga has deceived climbers. But this interpretation still begs the question: What was the furthest point they reached? As on Manaslu, her summit photos don’t prove anything. Finally, if they failed to reach the true summit, was Tseng aware of it?

Tseng’s summit picture, above, lacks geographical references. Photo: Grace Tseng/Facebook

A tricky summit area

In our Climber’s Guide to Kangchenjunga, Nives Meroi and Romano Benet of Italy describe the mountain’s confusing upper sections. On their first attempt in 2012, they joined with Horia Colibasanu of Romania and Peter Hamor of Slovakia. During the final summit push, the two Italians and Colibasanu chose the wrong couloir on the upper part of the mountain. Only Hamor reached the true summit. The other three found themselves on a lower central point, from which they could not advance.

The proper route up Kangchenjunga between Camp 3 and the summit. Photo: Nives Meroi/Romano Benet

No summit veteran on Tseng’s team

Gelje Sherpa had been on Kangchenjunga only once before guiding Tseng. At that time, he only reached 8,010m. Nima Gyalzen, another of Tseng’s guides, had been there with Mingma G, but neither summited on that occasion.

That means that no one on the team had been to Kangchenjunga’s summit area before. There were completely alone on the mountain, after the only other group on the peak that season had left. Before leaving, that second team fixed ropes until approximately Camp 4. One day before Tseng’s summit push, Gelje reported he had fixed some more, until 8,050m.

According to the article on Mozgasvilag.hu., Nima Gyalzen went ahead, fixing the ropes on an extremely long summit day. “It took almost 20 hours to reach the top and another seven hours added to get down to Camp 4,” Pasang Rinzee reported later. He also posted a video on the way up, cited by the article’s authors:

Their conclusions

After studying hundreds of pictures and video frames, both from Tseng’s team and other Kangchenjunga climbers, Pinter and KrisAnnapurna concluded that “the team apparently deviated to the left of the normal route above Camp 4, and they were climbing towards a huge, diamond-shaped boulder, a clearly visible feature even from afar, on the left side of the couloir.”

They say that it would have taken hours to reach the true summit from that secondary point: “They would have needed to get down to the saddle before the summit, then join the normal route and the long traverse to go around the summit pyramid,” they wrote.

A summit video that Grace Tseng posted shows Yalung Kang briefly when she waves a Taiwanese flag at 7:15 in the Facebook video below.

The figure in yellow above Tseng is heading to the wrong summit. Photo: Screenshot

As the article notes, Yalung Kang is not where it should be, and some parts of the ridge in the photo are not visible from the true summit.

The article concluded that Tseng and the Sherpa team stopped at a lower point left of the true summit, an area known as The Pinnacles. The 8000ers.com team agreed.

The yellow dot marks The Pinnacles, where the authors conclude that Tseng’s team stopped. Photo marked with location by Mozgasvilag.hu

Geographical references at The Pinnacles, compiled by Rodolphe Popier of 8000ers.com. Photo by Ferran Latorre. (Mur Difícil means “difficult wall” in Catalan).

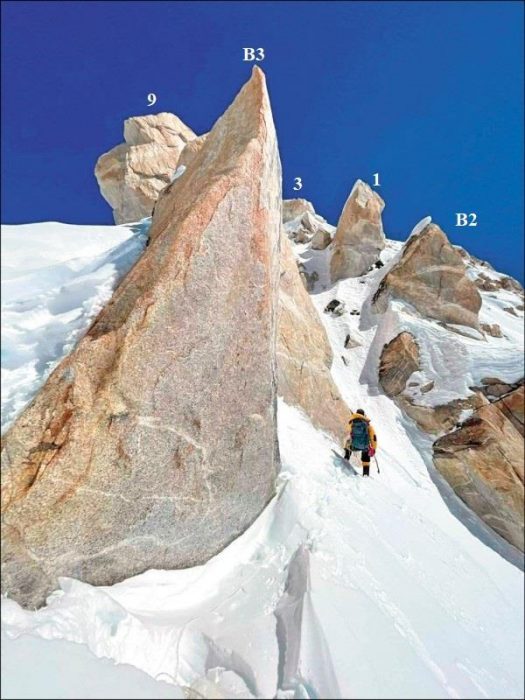

In this image, a member of Grace Tseng’s Kangchenjunga team approaches The Pinnacles. Rodolphe Popier has added geographical references (with numbers) for each feature.

The 8000ers.com point of view

Asked by ExplorersWeb, 8000ers.com team member Rodolphe Popier, an expert in identifying geographical features on summit area photographs, told ExplorersWeb that he sides with the article’s conclusion.

“From the pictures analyzed, it’s logical to conclude Miss Tseng wasn’t on top of Kangchenjunga,” he said.

Frame from Grace Tseng’s Kangchenjunga video on Facebook.

But he added: “We still wonder if they [knew] they missed the top since they had a clear sky. But it’s possible that they just made a mistake since they hadn’t any background knowledge of the mountain.”

Tomorrow, the 8000ers.com team will publish a complete report about Kangchenjunga’s summit area.

What Grace Tseng, Gelje, and Nima Gyalzen say

Grace Tseng told us that she had already asked her Sherpa team to confirm that they had not reached the wrong summit point. Both Gelje Sherpa, who led the team, and Nima Gyalzen, who has climbed with Tseng on all her 8,000’ers, confirmed to her that they had reached the “real summit”. As far as we know, however, they have provided no evidence.

Tseng told ExplorersWeb that she had no InReach device at the time and so didn’t record a track. But Gelje had one, “but it went off at 8300m because the battery was dead,” he told ExplorersWeb. “I didn’t notice at the time. [On the way up] we followed the instructions Dawa [Chhang Dawa Sherpa, CEO of Seven Summit Treks] gave us over satellite phone.”

Grace Tseng herself, of course, didn’t know the way to the top. She totally relied on her Sherpa guides. “When we finished climbing, there was no higher mountain in front of us,” she said. “As far as I know, it [was] the real summit.”

Recently she wrote on social media, in response to the Mozgasvilag.hu article, “I think that under the leadership of the experienced Sherpa team, we had no reason to go to the wrong summit.”

2022 Kangchenjunga summits

Gelje Sherpa summited Kangchenjunga in the spring of 2022 with Adriana Brownlee, a few months after the Tseng climb. Ordinarily, he should have noticed if they reached a different point. Yet on that subsequent climb with Brownlee, the whole summit push took place at night, and they followed ropes fixed by others. Their summit photos, shot at 4:30 am on May 14, show only a thin line of dawn light in a dark blue sky:

The fixed ropes are also key in this case. This year, Mingma G and his Imagine Nepal team were in charge of fixing the ropes. Didn’t they find the ropes left behind by Tseng’s team the previous fall? And if so, did they follow them to the top?

Well, the answer is that they did find the ropes and they did follow them — to Mingma G’s dismay.

The misleading white rope: Mingma G and Chris Warner

After their first summit attempt last spring, a frustrated Mingma G texted ExplorersWeb: “April 27-28, we had a very hard time opening the route to the summit. At a certain point [above 8,300m] in the middle of the night, we mistook some old ropes and followed them — up what proved to be the wrong direction. When I found out and corrected course, we were already out of time. I didn’t want my team to take too many risks, so we aborted.”

A member of Mingma G’s team fixes ropes on Kangchenjunga in April 2022. Their new rope is the darker one; Tseng’s is the old, white one. Photo: Chris Warner

American Chris Warner was with Mingma G and his rope fixers. Today, he shared with ExplorersWeb what happened that day. Chhiring Sherpa, Pemba Sherpa, and Chris Warner went ahead of the group.

“We followed a few hundred metres of ‘fresh’ white rope up the wrong gully system on Kangchenjunga,” he told ExplorersWeb. “We only followed [it] because a brief snowstorm hit the mountain when we were at the point where we should have traversed right on the normal route. Unable to see, we simply followed the white rope.

“The rope just stopped below a giant boulder, on an approx. 8,400m bump along the summit ridge.

“Traversing off that sub-summit without a rope (we had run out) was too dangerous in the spring snow. The only way off was either by rappelling down to a place where you can then climb toward the true summit or by traversing a very steep rock slab. To return by that route would have required ropes left in place. We looked for a solution but were forced to admit defeat.”

Warner added: “The ropes that we followed seemed quite new. The Sherpas and I thought that the [white] rope was from the fall of 2021, and the only team that had been there then was Grace Tseng’s team. We estimated it would be at least three hours to fix from that 8,400m point to the true summit.”

A white rope is clearly visible in Tseng’s videos:

Warner went on: “The team was below us and we reported to them that it was the wrong summit, so Mingma G made a lower traverse to back to the real route. By then, it was too late in the day. Approximately 20 of us were following that white rope, but only the three of us reached the end of it.

“When we eventually reached the true summit via the correct route, I saw no white rope on those last few hundred metres.”

In fact, the fixed rope to the summit in spring 2022 was blue:

Shehroze Kashif on Kangchenjunga’s summit, spring 2022. The blue fixed rope is seen on the left. Yalung Kang is above the climber’s fist. Another peak, Jannu, rises from the clouds in the background. Photo: Shehroze Kashif/Instagram

“Her videos did show more snow than we encountered, especially around that giant boulder where the ropes ended,” Chris Warner conceded. “Maybe they were simply able to walk towards the summit.”

Warner does not believe the end of the ropes could be in any way mistaken for the summit.

“For one, the boulder where the rope ended towers above your head (its top would be the summit). And as shown in the photo below, you can clearly see past the boulder to the true summit.”

The place where the white rope ended. “You can see the true summit in the pic,” Chris Warner said. “The summit is just behind the [distant] triangle of rock.”

Tseng: “We continued without ropes”

We asked Grace Tseng if she had stopped at the end of the rope or eventually climbed without them on the final sections.

“Summit day was so long!” she answered. “We did not set enough rope, so we had to find our way to the summit. Three Sherpas were with me. The first time we reached a place and saw no real summit, so we went down to another top and another…In the end, we finally saw no higher place around, and Nima [Gyalzen] checked it was the real summit. That’s where we took the summit pictures.”

One of Tseng’s summit photos, showing no rope.

Yet their supposed summit video shows the team clipped to a white rope, below.

Group summit picture, provided by Grace Tseng to ExplorersWeb.

After the Manaslu controversy about her speed climb, we said that only Tseng and her team really knew what had happened that day. On Kangchenjunga, we are not even sure if they actually knew where they were when they took their summit pictures.

We have asked Gelje Sherpa about the tracker he was reportedly carrying, but we have had no answer yet. Gelje is currently attempting a new route on Cho Oyu.

In the end, what we have is Tseng’s word against highly unclear evidence — exactly what happened on Manaslu months later. While Tseng continues to maintain the integrity of her claims on both mountains, questions continue about her GPS tracks and summit pictures on Manaslu. ExplorersWeb is still investigating.

Grace Tseng insists that she intended to break no record on Manaslu. She feels unfairly treated and just wants to be believed, like any other climber.

“Climbing is [supposed to be] a very happy thing, but I don’t know why it became so complicated…Now I just want to cry,” she wrote on social media, after finding out that 8000ers.com has rejected her Kangchenjunga summit.

What next?

Recently, Tseng told ExplorersWeb that if she finds the funding, she wants to try a fast ascent on Everest without supplementary O2.

If she manages to get there, she better make sure that she climbs in such a way that leaves no room for doubt. This means having other climbers around her besides her paid staff. She also needs a live tracker to map her full ascent, clear summit pictures with plenty of reference points, and none of those wonky Instagram filters that she likes so much.

Only then she will be able to do something without the controversy that has bedeviled her recent climbs. Luckily, Everest is the right place for plenty of company, anyway.

Manaslu 2022 summit picture: Grace Tseng (left) and Nima Gyalzen Sherpa. Photo: Grace Tseng/Facebook