Paleontologists have found the first complete skull of a controversial prehistoric bird. Known as Vegavis iaai, the bird thrived in late-Cretaceous Antarctica, then a tropical paradise. About a million years before the asteroid that wiped out 75% of life on Earth, it went extinct.

Its fossilized skull, first discovered in 2011, has finally been analyzed. It fills in gaps in ornithologists’ understanding of Vegavis iaai — and highlights the striking ecological diversity of early birds.

A controversial bird

In 1993, a team of paleontologists found remnants of a previously unknown species embedded in two pieces of rock on Vega Island, off the coast of Western Antarctica. They named it ‘Vegavis iaai,’ or “Vega bird” in Latin.

The fossil’s discoverers said it was a waterfowl, a broad order encompassing everything from geese to loons. That’s where the controversy began.

Most of the time, when fossils are controversial among paleontologists, it’s due to questions about their authenticity. One of the most controversial fossils in history was the Piltdown Man. In 1912, an amateur archaeologist combined an orangutan mandible with the skull of a human and claimed he had found it in prehistoric English gravel beds. And in an example of a genuine mistake rather than fraud, the infamous tooth of the Nebraska man turned out not to be from a prehistoric North American ape as originally proposed, but from a peccary.

But ornithologists never doubted that Vegavis iaai was some sort of dinosaur. Instead, they couldn’t decide what kind of dinosaur it was. Dinosaurs included birds, but not all birds were dinosaurs. Was this the ancestor of a duck? A chicken? Or was it a completely different kind of dinosaur that just happened to look like a modern bird?

The lifestyle of Vegavis iaai

A recreation of Vegavus iaai from 2023, before the new paper. Photo: Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche/Trevor Worthy

Although its exact identity was puzzling, the fossil of Vegavis iaai provided important clues about its lifestyle. It had flat feet to propel it underwater. A fast metabolism allowed it to thrive at high latitudes but kept it hungry for food. And it could sing.

In fact, Vegavis iaai wasn’t just an early singing creature. As far as we know, it was the earliest. Most dinosaurs couldn’t sing, and although avian dinosaurs — birds — lived prior to Vegavis iaai, they lived in silence.

But did Vegavis iaai evolve into a modern species, or was it peculiar to the late Cretaceous? To answer that question, paleontologists needed the missing link — a skull.

Shedding light on prehistoric Antarctica

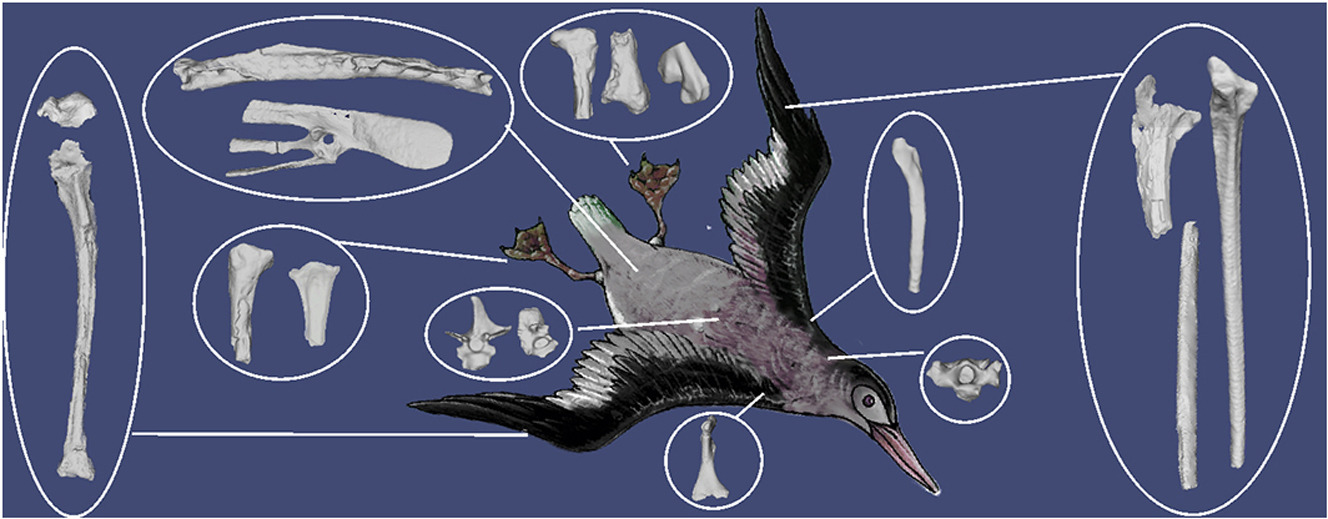

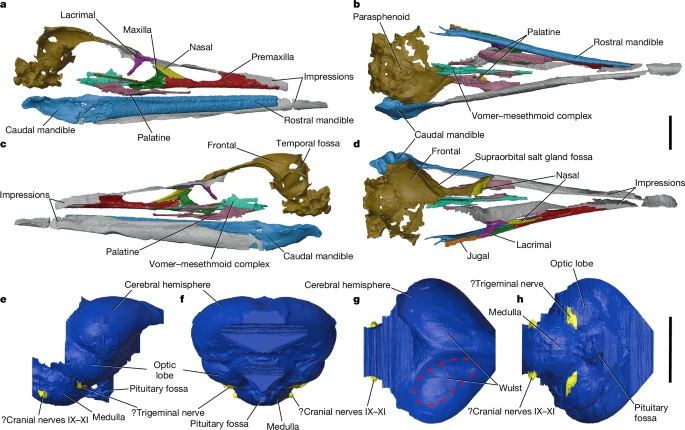

The digital recreation of the new skull. Photo: Torres et a 2025.

A paper published in Nature last week reports, for the first time, the 2011 discovery of a complete Vegavis iaai skull. Over the course of 14 years, the authors carefully analyzed the skull, including the use of X-ray microscopy to create a 3D model.

Its features don’t slot neatly into any modern bird family. Vegavis iaai had the flat feet of ducks but a sharp, narrow beak like a loon. Thick muscles supported its jaw against water pressure, allowing it to bite underwater. Its skull, though, lacked the bony spurs at the base of the beak common to most modern birds.

It was a waterfowl, but it wasn’t anything as familiar as a duck or a goose. In fact, the authors show that the closest relative to Vegavis iaai was another prehistoric Antarctic bird, Conflicto antarcticus. The kicker: unlike Vegavis iaai, Conflicto antarcticus dates from after the Chicxulub meteor killed all non-bird dinosaurs.

We know that birds survived the impact event because they existed before and, evidently, they exist today. But the new findings on Vegavis iaai make it the one lineage we can tentatively trace from immediately before the impact to immediately after.

An artist’s impression of Vegavis iaai swimming. Photo: Andrew McAfee/Carnegie Museum of Natural History