Imagine you’re a planetary geologist who studies meteorites. You know that Antarctica is a great place to find them — they tend to stick out on that windswept, white-and-blue continent. But the logistics of travel in Antarctica, combined with the size of most meteorites relative to a continental search area, makes for a daunting task.

What if you had a map?

That’s what Belgian glaciologist Harry Zekollari thought to himself over a decade ago. He passed the idea on to his colleague, Veronica Tollennar.

Tollennar might have the most interesting biography of any glaciologist on the planet. As reported by El Pais, the Dutch scientist is an accomplished flutist specializing in Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque music. She also studied civil engineering, a discipline that taught her to use artificial intelligence tools.

Dutch glaciologist Veronica Tollenaar used machine learning to generate this map of possible meteorite locations. The black spots are likely meteorite surfacing zones, and the pink tent symbols are research stations. Map: Veronica Tollenaar

Tollennar and a team of researchers applied those machine-learning skills to the question of meteorite hunting in Antarctica. They eventually published their findings and developed a public map that any scientist can use to home in on possible space rocks.

How did they do this? It all has to do with one of Antarctica’s most unique properties.

How the map was made

As meteorites fall on Antarctica, snow buries them, and the rocks eventually sink into the substrate of Antarctic ice. These ice layers flow in titanic glacial rivers, only stopping when they come up against obstacles like mountains. There, the ice coughs up its extraterrestrial treasures, creating zones where finding meteorites is relatively easy.

Until Tollennar and her map, scientists had to more or less stumble over these zones by looking for areas of “blue ice” — the compressed ice known to contain meteorites. But by using machine learning to map the movement of Antarctica’s subsurface glacial rivers, scientists can predict the best spots to hunt for meteorites. And some of those spots are relatively close to existing research stations.

A graphic from Veronica Tollenaar’s paper illustrates two ways that obstacles can cause submerged meteorites to surface. Illustration: Veronica Tollenaar Et al.

“Maybe only one in 100 meteorites is special. So, in order to get that special meteorite, you need to find the other 100 as well,” Tollenaar told El Pais.

Tollenaar posits that some 340,000 meteorites might be congregated in the zones on her map. She’s currently seeking funding to better explore some of those areas.

But as any fan of exploration knows, having a map is only half the battle. Especially in Antarctica.

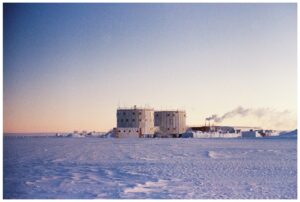

Antarctica’s unforgiving qualities make meteorite hunting a challenge, even with a map. Photo: Shutterstock

“The task of recovering Antarctic meteorites is only 10 percent science; the rest is training, planning and logistics,” said geologist Ralph Harvey, head of the Antarctic Search for Meteorites project.

Still, it’s work worth doing. Meteorites, especially ones preserved by Antarctic ice, allow scientists to study star formation and the evolution of life in our universe.