Antarctica is turning green as plants take over parts of the icy landscape. The change is happening far faster than expected, which could spell trouble for the frozen but still living ecosystems.

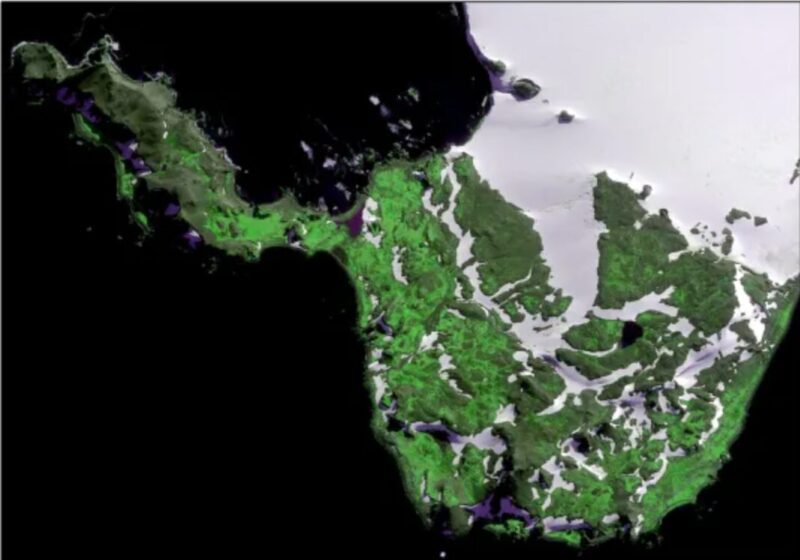

Satellite imagery shows that plant cover on the northern Antarctic Peninsula is 12 times higher than 35 years ago. In 1986, the greenery covered just one square kilometer. By 2021, it covered almost 13 square kilometers. The rapid growth continues to accelerate.

Since 2016, temperatures on the Peninsula have risen much more quickly than the global average. But it’s the loss of sea ice that seems to be responsible for Antarctica’s newfound greenery.

Mosses are the dominant species in the greened-up areas. The warmer temperatures and increased moisture have created the perfect environment for them to flourish. In turn, the mosses created more favorable conditions for other plants. As they take over previously barren land, soil begins to form. This nurtures any invasive species that make their way into the region.

A satellite image of Robert Island in the Antarctic Peninsula, showing the vegetation. Image: WorldView-2/DigitalGlobe

Invasion of the spores

“Seeds, spores, and plant fragments can readily find their way to the Antarctic Peninsula on the boots or equipment of tourists and researchers, or via more ‘traditional’ routes associated with migrating birds and the wind,” lead author Thomas Roland told CNN. “So the risk here is clear.”

Invasive species can quickly out-compete the few native plants in Antarctica’s fragile ecosystem.

Then, as the moss and plant cover replaces the ice cover, the peninsula will start to absorb more solar radiation rather than reflect it back into space, warming it further.

“Our findings confirm that the influence of [human-induced] climate change has no limit,” says Roland. “Even on the Antarctic Peninsula, this most extreme, remote, and isolated ‘wilderness’ region, the landscape is changing, and these effects are visible from space.

Besides the moss, the researchers found lichen, grasses, and red and green snow algae. Many studies in polar regions focus on the loss of sea ice. But here, the next step will be to analyze how quickly plants can colonize bare rock after the glaciers retreat.