After signs that arctic expeditions were set to resume after a two-year, COVID-induced hiatus, it now appears that global turmoil, poor planning, and climate change may kill the season prematurely.

Barneo

First, construction of the Russian ice station that goes up each spring 100km from the North Pole to host Last-Degree skiers and other adventurers was, not surprisingly, canceled. Barneo hasn’t operated since 2018. Many wonder if it will ever run again.

Lena River

Photo: Charlie Walker

No word from Charlie Walker of the UK since February 24, when he started his 1,600km northward trek along the frozen Lena River from Yakutsk, Russia. His starting date couldn’t have been worse, as it coincided with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Presumably, he is continuing his trek but considers it unsuitable to post about it. We’ll update as soon as we hear anything.

Greenland to Baffin Island

Marceau and company: dogsledding for now. Photo: Pascale Marceau

Conditions do not look suitable for Pascale Marceau, Scott Cocks, and Jayme Dittmar to cross from Greenland to Ellesmere Island. Their plan was then to continue south along Ellesmere’s east coast and eventually to Baffin Island. But the ice bridge between Greenland and Canada has not formed this year. Open water and swiftly moving pack ice fill the channel all the way north to the Arctic Ocean. The satellite photo below shows the state of the crossing area, marked in red, as of Saturday, March 12.

“The bridge doesn’t look promising,” Marceau admitted in her most recent post four days ago. “Our timing is landing us on high tide (full moon) too, which is not optimal.”

They are currently dogsledding over the Greenland ice cap toward the crossing area, from which they would start skiing and hauling sleds. If the ice bridge doesn’t allow a crossing, they will move to plan B, C, or D in Greenland, she says.

The ice bridge, which formed most years for centuries, allowed Greenland Inuit to cross to Canada to hunt muskoxen and return home in late spring. Since 2007, the bridge has been intermittent.

Ellesmere Island

Ray Zahab and Kevin Vallely set off from Grise Fiord last week. Photo: Ray Zahab

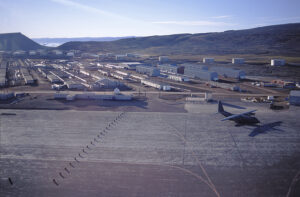

On March 2, Ray Zahab and Kevin Vallely left the hamlet of Grise Fiord, on the south coast of Ellesmere Island, to manhaul 1,100km to Alert, a military base on the island’s north coast.

Barely 10 days later, the pair were back in Grise Fiord, humbled by the cold and hauling conditions. They had chosen to leave in early March, at the coldest time of year, perhaps to claim a winter start: The two previous expeditions to cover the length of this 10th largest island in the world began after the spring equinox.

The early launch meant consistently cold temperatures of -30 to -35˚C. Snow at those temperatures is extremely abrasive and hard to pull over. The duo were making 10km a day — actually a reasonable distance at that time of year, with short days and fully laden sleds over sandpapery snow. But they had expected to make 25 to 30kpd in order to finish their expedition in 40 to 50 days.

I’ve written a couple of books about Ellesmere Island, and I’ve covered much of their route. To me, their approach was flawed in several ways. Apart from guaranteeing themselves slow going for the first two or three weeks by leaving so early, their inland route — while perfectly feasible — is a lot slower than sticking to the sea ice.

Some years ago, then 65-year-old Jon Turk and his partner, Eric Boomer, averaged 25kpd by keeping to the sea ice during their circumnavigation of Ellesmere. If you need to make big distances, as Zahab and Vallely did, inland is not the way to go.

Their projected route, in red. The sea ice route, in green, is longer but much faster.

Why is the sea ice so much faster? First, even low inland routes, like the one they chose, involve slight uphills. Second, the twists and turns of those narrow valleys lead to patches of soft snow, because the wind does not rake it as consistently as in the more open areas, especially the sea ice. Third, Ellesmere is a polar desert, and the little snow that does fall — while it can impede progress — does not always cover the rocks and gravel in those windswept passes.

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

This leads to some slow and picky maneuvering, if you want to preserve your sled by not dragging it over rocks.

Other times, there is no escape: You just have to drag it over bare sections. The heavy sled screams as if in agony as it scrapes over sharp gravel. Gelcoat and runners will never be the same. Two hundred metres of gravel will ruin a sled, though it will still serve adequately for the remainder of an expedition. But you do not want to bring a $7,000 Acapulka carbon sled on an overland Ellesmere journey.

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

At the same time, too flimsy a sled is also a mistake, especially at that cold time of year. On my first sledding expedition on Ellesmere, I had the bright idea to use a high-density polyethylene sled: It was lighter, cheaper, held all the gear, and flew north more easily and economically than a two-metre long fiberglass sled.

Unfortunately, sharp nubs of windblown sea ice and bits of gravel in the passes quickly sliced open the bottom of our sleds. It was early April, still fairly cold, and the plastic was brittle.

We had to spend hours each evening stitching the slits together with the snare wire in our repair kit. My partner’s sled had so many stitches (about 75) that he eventually bolted his skis to the bottom of his sled as runners so the stitches wouldn’t drag as much. He then had no skis to wear and had to posthole.

Already by day two, plastic sleds began to show major damage. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Zahab and Vallely didn’t mention whether they had problems with the similar plastic models they chose, but such delicate sleds might well have caused issues on a largely inland route.

The adventure athletes’ Instagram post back in Grise Fiord: