For three and a half days earlier this month, Eric Philips, 62, was in an environment that made his familiar Antarctic plateau seem almost hospitable. Sardined in a tiny capsule with three other amateur astronauts, he orbited our blue marble at 7.6km/sec. Outside, the blackness of space, with its microgravity and zero air and unseen perils of radiation and micrometeorites.

“What never gets old is Zero G,” Philips told ExplorersWeb. “It’s like being a child all over again.”

Previously, we explained how Philips’ late-career adventure came about. Two years ago, he guided a ski tour on the Norwegian Arctic Islands of Svalbard. One of his clients, Chinese-born Maltese citizen Chun Wang, was interested in talking about space travel. Not uncommon: Simple environments often appeal to polar types.

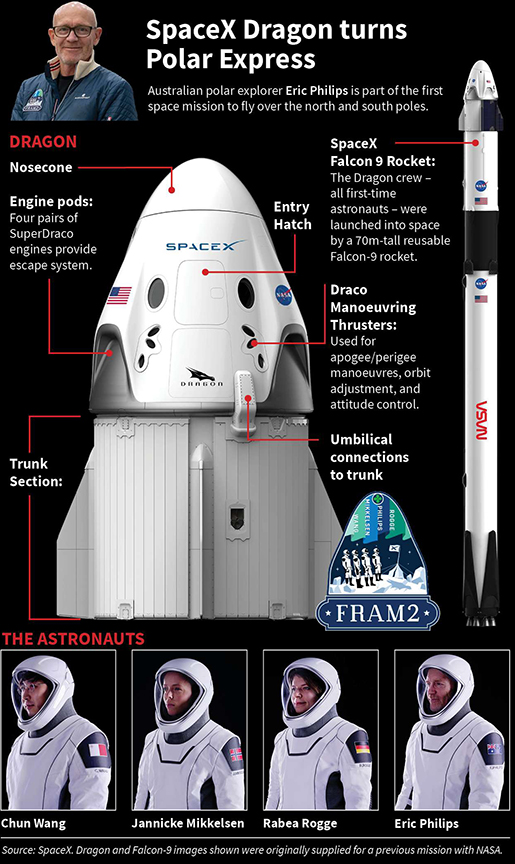

But in this case, Chun had the resources to do more than talk. He had made a fortune in bitcoin mining and wanted to buy a commercial flight on SpaceX. A few months later, he invited Philips, Rabea Rogge (a German robotics engineer and fellow skier on the tour), and cinematographer Jannicke Mikkelsen, based in Longyearbyen on Svalbard, to join him. Chun would cover expenses, in the range of $200 million.

Left to right, Eric Philips, Rabea Rogge, Jannicke Mikkelsen, and Chun Wang with SpaceX employees. Photo: Fram2

A year of training

For a year, Philips and his three partners trained for the mission, which they dubbed Fram2 after the famous Norwegian polar ship. Most of the training took place at SpaceX’s headquarters in Los Angeles. The Dragon capsule flew on its own, but they had to learn what to do in case something went wrong. Among the things Philips had to practice as the designated medical officer was inserting a catheter in case of an emergency. However, all went well.

“In the end, we used maybe one percent of our training,” said Philips.

Blast-off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Photo: SpaceX

On March 31, after several days in quarantine near Cape Canaveral in Florida to avoid catching a bug before the flight, it was time to launch.

Centrifuge training had given some practice with the tremendous G-forces of a rocket tearing itself free of Earth’s gravity, but even that didn’t compare to the 4.6 Gs of the real thing. It was enough for them to feel their organs compress, said Philips. But it didn’t last long.

The launch trajectory. Photo: SpaceX

Kármán line

They cleared what is called the Kármán line, 100km above the Earth, at which point they were officially astronauts. Soon, the main engine expended its propellant and fell away. Almost immediately, the second engine kicked in, propelling them to an altitude of 200km. From there, onboard thrusters lifted the capsule into orbit, some 450km above the Earth.

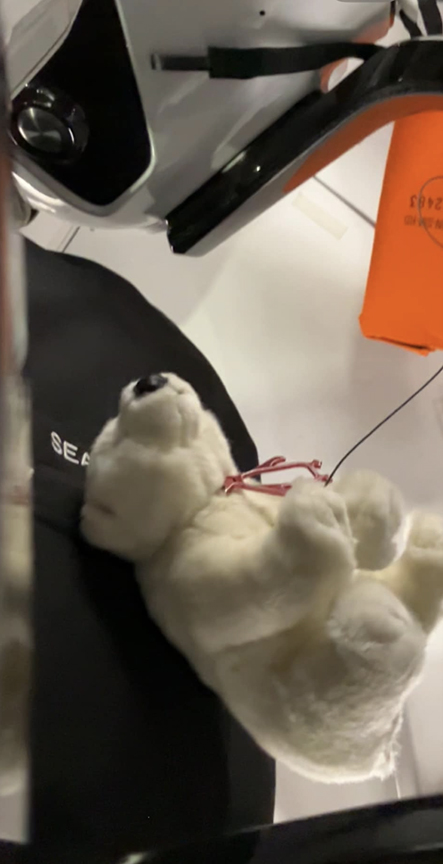

The first sign of microgravity Philips noticed was the loose ends of his restraint straps beginning to float. At the same time, a mascot that astronauts call the Zero G Indicator began to float around the 2.5-meter-wide capsule. For this mission, their Zero G Indicator was a stuffed polar bear wearing an emperor penguin necklace.

The crew’s Zero G Indicator. Photo: Eric Philips

This wasn’t just a nod to Philips’ background or where they met. This was the first time a spacecraft was planned to orbit the Earth via the Poles. From the 1957 launch of Sputnik until now, they have all been, from our perspective, “horizontal” orbits, not vertical.

“Because of our polar orbit, the Earth rotated beneath us, so we passed over every part of it,” Philips told ExplorersWeb. “We’re told this is a blue planet, because of all the oceans. But we were often over whiteness.”

Pure silence

In orbit, Philips noticed how quiet it was. Freed from gravity and without the friction of the atmosphere to slow them, they flew (or rather, fell) around the Earth with only occasional need for the booster to kick in, to keep their orbit from deteriorating. When it fired, sparks appeared outside the window, like a little fireworks show.

SpaceX broadcast the launch on its website, and a program called Zero Six Zero showed the Earth in more or less real time, with a simulated version of the capsule moving above it. In almost no time, they made their first pass over the South Pole. Forty-five minutes later, they flew over the North Pole. Orbiting at 27,000kph, it took them just three-quarters of an hour to travel halfway around the world.

Every day, they went through multiple phases of darkness and light. They made 55 orbits in all. Always, Philips delighted in “the sheer joy of microgravity.”

The Dragon’s first pass over the South Pole, minutes after achieving orbit. Image: Zero Six Zero

“What surprised me is how quickly I adapted,” said Philips. “I’m sensitive to motion sickness, and I was likely to get terribly space sick. But the first day was great. On the second day, we all experienced a little nausea but quickly recovered.”

A warm capsule

The interior temperature of the capsule ranged from 24˚ to 28˚C — warm for polar travelers. When they needed to sleep, they climbed into thin sleeping bags and just floated around above their seats, bumping lightly into one another as they slept.

During the day, drifting around in the cramped space, they were often “a tangle of limbs,” said Philips. His experience of being stuck in a small tent in Antarctic blizzards for three or four days at a time came in handy here.

Besides the otherworldly sensation of microgravity, everyone’s favorite experience was their time in the Plexiglas cupola — a clear dome atop the capsule, just big enough for one person at a time. From there, they could take turns looking at both the blackness of space and our amazing planet below. The Plexiglas was solid enough to repel radiation and any micrometeorites that might strike it. During launch and splashdown, a protective nosecone covers the cupola.

Philips knew from his prior reading that, contrary to the old myth, the Great Wall of China is not visible from space — and sure enough, it isn’t. But he did notice at night how bright China was with artificial lights, “far more than any other country.”

What he saw

He also identified other areas, both natural and manmade: their launch site at Cape Canaveral, the mountains of Alaska, and Svalbard, the archipelago that brought them all together. Philips also made out parts of Queen Maud Land in Antarctica, although at this time of year, darkness or twilight had settled over much of the White Continent.

The crew had 11 large satchels tucked away in a cargo section, containing food and water for five days. “It was like packing a sled,” recalled Philips. The Australian was even able to enjoy coffee in space, although it probably didn’t measure up to the typically excellent coffee in his own country.

For unclear reasons, SpaceX has always been shy about its onboard toilet facilities, and Philips and the others had to sign an NDA not to discuss it. Some space aficionados have pieced together information about it, however. Philips admitted that on such a short-duration flight, astronauts are administered enemas before launch to simplify the first couple of days.

700 astronauts

Since Yuri Gagarin, there have been almost 700 astronauts, but counting these four, there have only been 11 tourists who have gone beyond suborbital experiences and into outer space. As part of their program, they performed some 22 experiments, including taking the first X-ray in space and growing mushrooms. Cinematographer Jannicke Mikkelsen filmed. But largely, it was about soaking up an out-of-the-world experience.

When it came time to descend, they packed everything away — including the Zero G Indicator — put on their suits and strapped themselves in. “It was like being in a sailboat and preparing for an impending storm,” said Philips. “You do your best to prevent items from flying around.”

Their reentry also generated 4.6 Gs, but their brief time in weightlessness made it feel even more forceful than during the launch. Meanwhile, the temperature outside the capsule rose to 2,000˚C from friction in the atmosphere.

The Dragon splashes down with the Fram2 crew. Photo: SpaceX

Two drogue parachutes deployed at about 5,500m in altitude while Dragon was moving at approximately 560kph. At about 1,800m, the drogues pulled out the four main parachutes. The Dragon hit the water at about 25kph off Oceanside, California — the Dragon’s first Pacific splashdown.

A ship waiting five kilometers away then came and winched the capsule on board. All the astronauts were able to exit the hatch by themselves, although one was a little shaky walking to the medical bay.

Jannicke Mikkelsen, top, and Eric Philips, still on Cloud 9 after splashdown. Photos: SpaceX

‘A hurricane raged in my mind’

But after such an intense, at times ecstatic experience — microgravity, seeing our planet for the first time from space — there was bound to be a hangover. Philips recalled:

At the medical bay, my body went into shutdown. It was difficult to communicate with people in any meaningful way. A hurricane was raging in my mind. I could answer questions like, ‘Are you in pain?’ with no problem, but for two or three days, I couldn’t describe the experience.

Days later, they still experienced floating sensations. Once at breakfast, Philips imagined he could float over to the buffet to get his food.

While their extraterrestrial experience made some past astronauts a little “spacey” in their afterlife on Earth, Philips isn’t concerned.

“I’ll remain the staunch skeptic I’ve always been,” he says.

Image: Zero Six Zero