Astronomers have announced a candidate for the universe’s first generation of stars. While sifting through observations of the earliest known galaxies, they flagged one small dwarf galaxy, GLIMPSE-16043. Unlike every galaxy we have observed before, it doesn’t bear any signs of recycled stellar material.

Astronomers have theorized the existence of this first generation of stars, which formed not from the ashes of their ancestors but from primordial hydrogen and helium. Many candidates have previously cropped up, but none have won popular support. GLIMPSE-16043, however, may have what it takes to stand the test of time.

‘Population III’ Stars

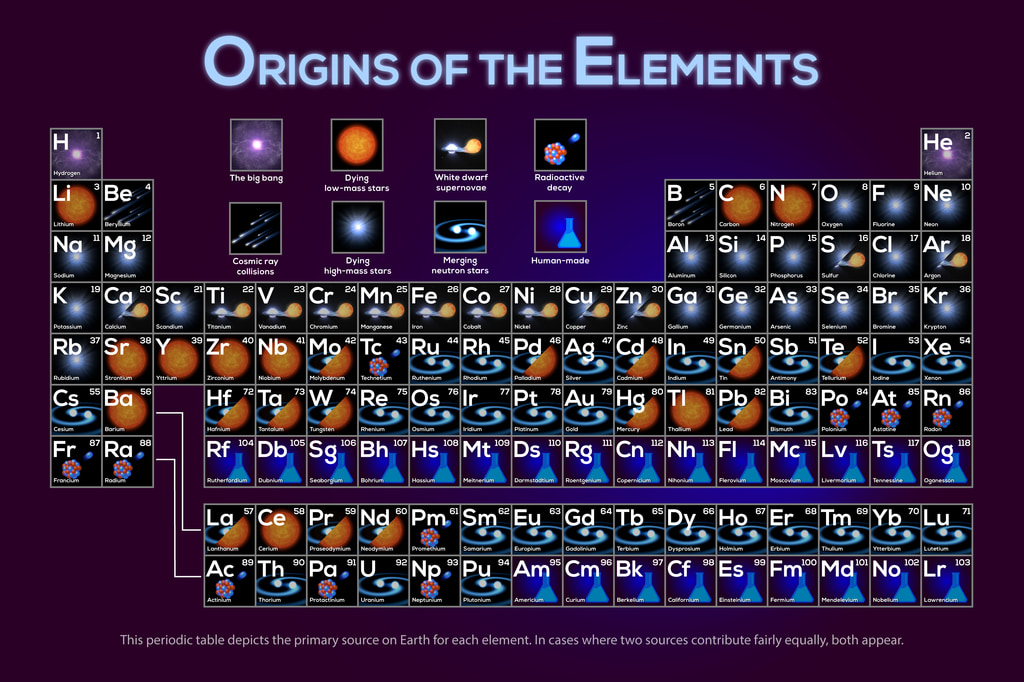

This periodic table shows the origin of each element. The Big Bang is only responsible for the production of hydrogen and helium. Photo: NASA

The Big Bang only created four elements: hydrogen, helium, and tiny amounts of lithium and beryllium. No oxygen, no iron, no carbon. In short, none of the elements that make up our solid, dynamic world.

Those did not arrive until much later, when the first stars died in massive explosions called supernovae. Deep in the furnace of their cores, they had forged all of the elements up to iron. Their supernovae flung these elements out across interstellar space, seeding the gas with metals that would work their way into the next generation of stars. (Astronomers call any atom heavier than helium a metal, presumably because they want to drive chemists into a blind rage.)

When early astronomers observed the Milky Way, they found this second generation of stars lurking in the ancient center of the galaxy and at the far-flung edges. They called them Population II stars to distinguish them from the much more metallic, familiar Population I stars that make up the Milky Way. These include our Sun.

By the time astronomers got around to theorizing the existence of an even earlier generation of stars, the naming convention was set. The first stars in the universe are Population III.

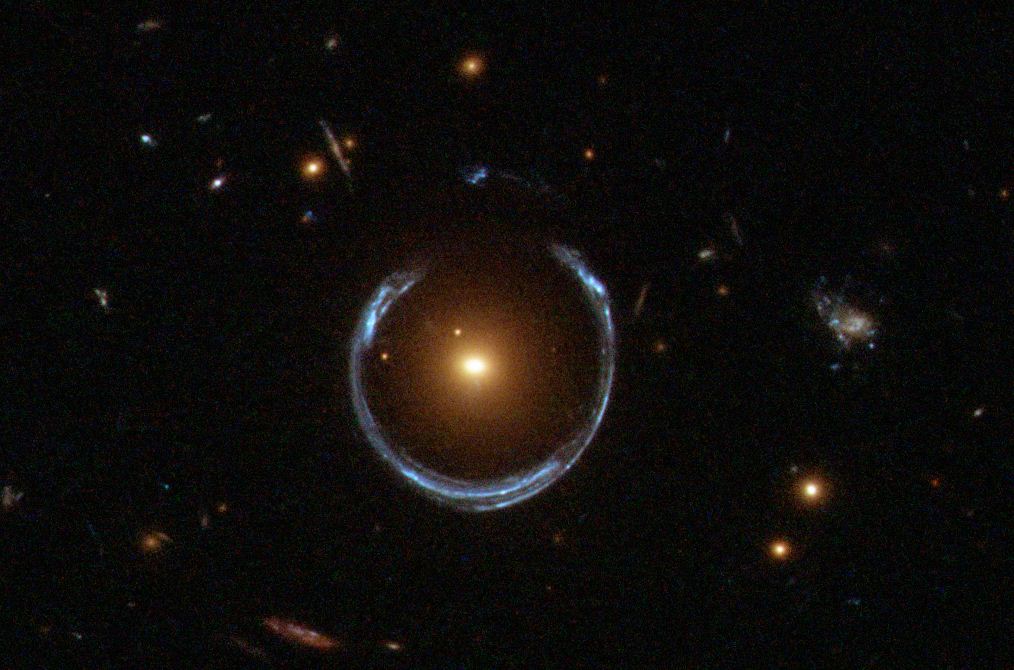

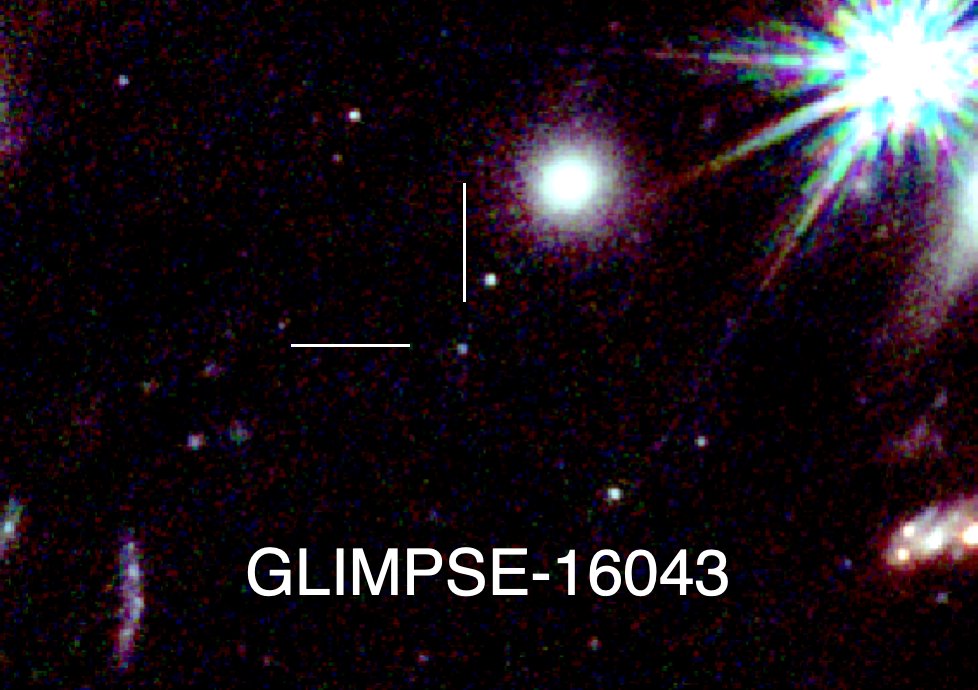

The crosshairs indicate the galaxy that may host Population III stars. Photo: Seiji Fujimoto

A galaxy of only hydrogen and helium

People cannot exist without metals. Planets cannot exist without metals. Not even the dust grains that float in interstellar space can exist without metals. Without metals, there are only clouds of gas and stars.

That’s what would comprise this possible candidate for Population III stars, a dwarf galaxy from only 900 million years after the Big Bang. GLIMPSE-16043 is only visible to us because it lies behind a much larger, much more nearby galaxy. The gravity of that foreground galaxy magnifies the light of GLIMPSE-16043 and reroutes it toward us. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) excels at photographing these “gravitationally lensed” galaxies.

The team that identified GLIMPSE-16043 investigated thousands of lensed galaxies observed with the JWST. GLIMPSE-16043 was the only one that matched their criteria. Hydrogen makes galaxies redder, so to identify galaxies dominated by hydrogen, the team restricted their search to galaxies that appear brighter when photographed through a red filter.

Then they used how bright a galaxy is under different colored filters to calculate its age. They kept only the hydrogen-dominated galaxies that dated from 700 million to 1.2 billion years after the Big Bang. That’s when Population III stars would have existed.

GLIMPSE-16043 passed these tests with flying colors. At about 900 million years after the Big Bang, it seems to have almost no metals. When we look at this tiny little dot on a pixelated image, we may be looking at some of the first stars in the universe.

Confirming this will be difficult. The dwarf galaxy is very faint, and the JWST is probably not sensitive enough to do anything other than image it in different color filters. These filters are equivalent to putting giant buckets out in the rain to catch all the water you can. They miss the fine detail in each raindrop that would reveal the presence or lack of metals.

If this galaxy is indeed made of Population III stars, it is probably one of the last stragglers from that era. We may need to wait for a better bucket to confirm the nature of GLIMPSE-16043. Fortunately, the galaxy isn’t going anywhere.