Blink and you’ll miss it: two momentary blue flashes in a set of photographs of a serac fall. The man who took them has a theory that hits on unanswered questions in physics.

Astrophotographer Li Shengyu has a history of taking internet-breaking photos of the sky. As an award winner of Beijing Planetarium’s 2023 photography contest and a viral sensation for his videos of auroras in Inner Mongolia, he knows how to direct eyes to the stars. Now he’s got amateur astronomers looking at the ground.

Yesterday, SpaceWeather.com published time-lapse footage by Li showing a serac collapsing on Sichuan’s Mount Xian Nairi. As a sheet of ice cascades down the face of the mountain, a blue light follows it in brilliant flashes.

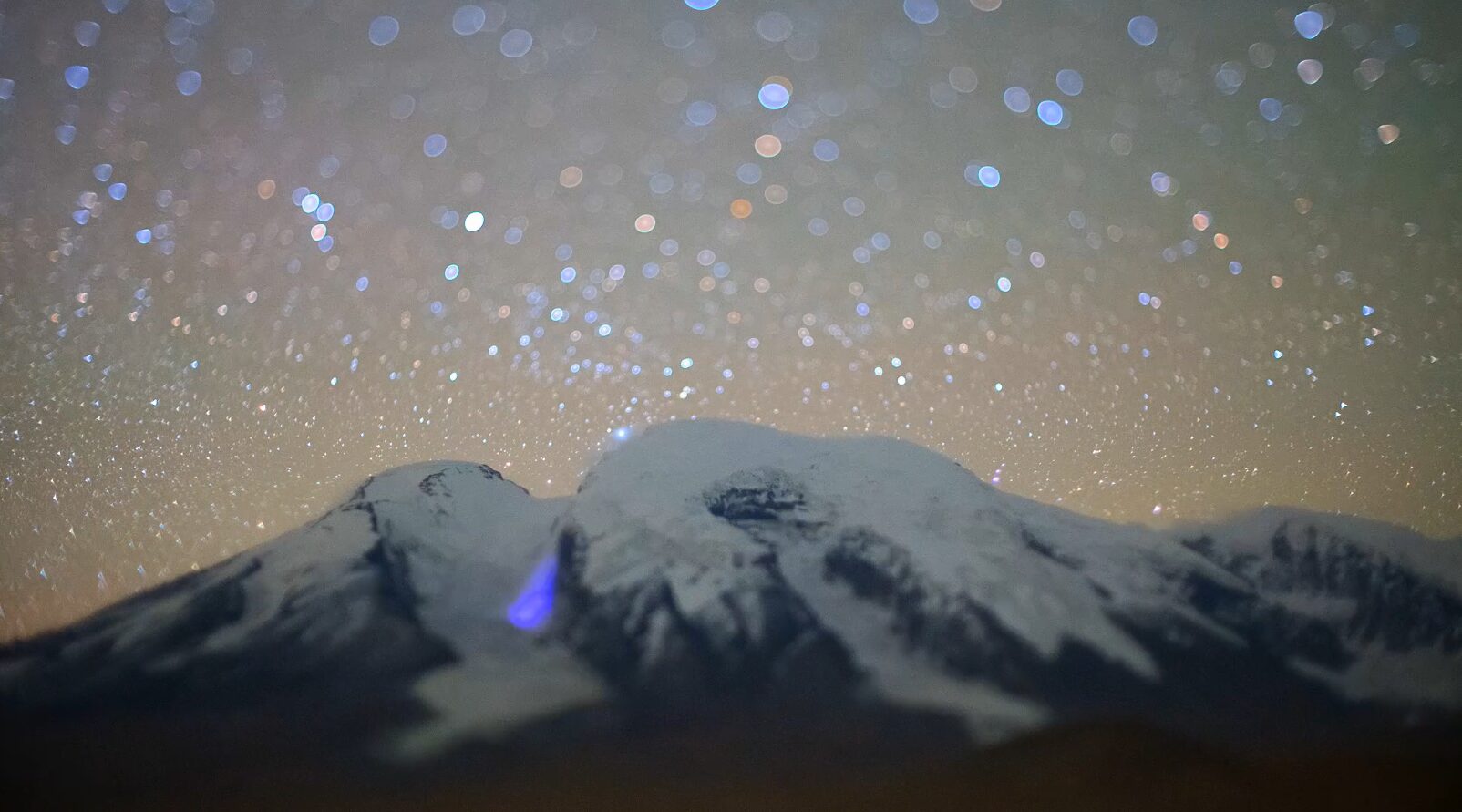

Li Shengyu’s avalanche footage of Mount Xian Nairi/Chenrezig, taken October 27. Photo: Li Shengyu

Blue lights illuminate a sacred mountain

An alternate view of Xian Nairi. Photo: Trip Advisor user M27***10

Mount Xian Nairi stands just over 6,000m tall and lies in the Garzê Autonomous Tibetan Prefecture of southwestern Sichuan. Also known in Tibetan as Mount Chenrezig, it forms one of a triptych of holy mountains that keep watch over the surrounding landscape. As an important pilgrimage site in Tibetan Buddhism, climbing it or its sibling peaks is forbidden.

On October 27, Li Shengyu set up his camera at the foot of Xian Nairi. His goal: to capture the glory of the mountain against a backdrop of traveling stars. As the Earth spins throughout the night, the stars appear to rotate in the sky. Long-exposure or composite photographs taken over the course of a night show comet-like smears known as star trails.

Star trails over the Atacama Desert in Chile. Photo: Adhemar M. Duro Jr / ESO

He got his star trails, but he also got what he suspected was a previously unobserved natural phenomenon: his flashing blue lights. Li reached out to other members of his astrophotography community. They spent a lot of time photographing mountains. Had anyone else seen anything like this?

A second avalanche glow

As it turned out, one had. Earlier that month, astrophotographer Lu Miao captured a similar event on 7,546m Muztagh Ata in Xinjiang. In her video below, a cornice fall appears to trigger a luminous blue glow, more enduring than the one on Xian Nairi.

Li told SpaceWeather.com that neither he nor Lu had noticed the flashes in real-time, only in their photographs. “However, I asked some friends who frequently photograph snow-capped mountains,” he added, “and one of them mentioned having seen blue light with the naked eye during an avalanche, though they didn’t capture it on camera.”

In the month since he recorded the lights, Li has formulated a theory. “Our initial hypothesis is that the luminescence may result from friction-induced lighting during the fragmentation of ice.”

Physicists have a word for this effect: triboluminescence.

A mysterious optical effect

The first known description of triboluminescence dates all the way back to 1605. “It is well known that all sugar, whether candied or plain, if it be hard, will sparkle when broken or scraped in the dark,” wrote Sir Francis Bacon in his work Novum Organum. “In like manner, sea and salt water is sometimes found to shine at night when struck violently by the oar.”

Not to be outdone, 20th-century physicist Richard Feynman summarized the phenomenon more prosaically. “When you take a lump of sugar and crush it with a pair of pliers in the dark, you can see a bluish flash. Some other crystals do that, too. No one knows why. The phenomenon is called triboluminescence.” The video below shows the effect on a LifeSaver.

We’ve learned more since Feynman described triboluminescence, but not much more. It occurs when a crystal is fractured. Sometimes, the light comes from a current jumping from one side of a fault line in the crystal to the other, stripping the nitrogen in the air between of its electrons. Temperatures soar, and the surrounding molecules radiate like they’re in a furnace. That’s the same process as lightning, though on a much smaller scale.

Complicating this pat understanding of triboluminescence is that other crystals radiate from a mix of ionized nitrogen and, seemingly, the surfaces of the cracked crystal. Still others don’t radiate from nitrogen at all. So what are all the processes contributing to the flash? On the broadest scale, it’s not clear.

Fracturing ice might cause mini-lightning

On the scale of an avalanche, however, the picture starts to come together. As water freezes, any momentary electrical imbalances get frozen in with it, leaving the ice with a permanent magnetic field. The falling serac in Li’s video smashes against several rocky outcroppings on the way down. If a crack lands in the right location for one side to be negatively charged and the other positively charged, triboluminescence could occur.

This is great news to anyone interested in avalanche science, since the resulting flashes could offer insights onto the composition of the ice and the key impact points. How much of a given cornice fall, for instance, is solidly glaciated? How do fractures spread within ice?

On the flip side, observing triboluminescence on a far larger scale than a sugar cube and a pair of pliers is a big deal for molecular physics. Crushed sugar sparks consistently, but out of all the avalanches filmed all over the world, we only have a few recorded instances of ice sparking. Why?

We don’t know, but next time you see an avalanche, keep your eyes wide open. Physics is watching with you.