The Mars weather report is in, and we’re seeing harsh conditions for the first few months of the new year.

For the first time in two Earth years, it’s spring on the Red Planet’s northern hemisphere, and high-resolution space cameras have caught sight of dramatic landscape shifts all across the disintegrating ice fields. Between avalanches, geysers, and katabatic winds, the Martian spring has been packing all the worst weather events into its small northern ice cap.

Ice avalanches are common in Martian spring

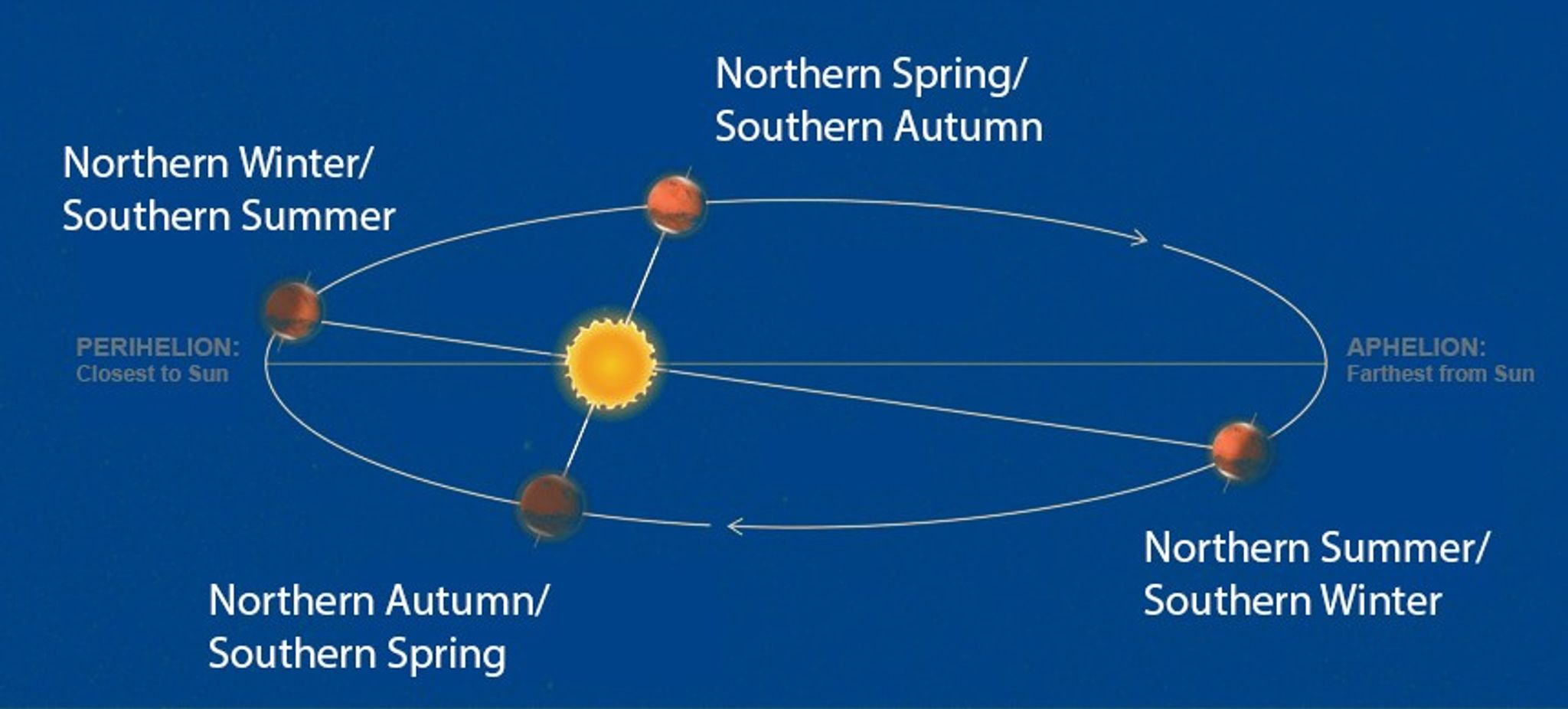

The seasons on Mars last around twice as long as those on Earth. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech

November 12 marked the new year on Mars, counted from trips around the Sun since a dust storm raged across the planet’s surface in 1955. Because Mars’ orbit is much more elliptical than the Earth’s, seasons are more extreme. On top of that, the thin carbon dioxide atmosphere offers little protection from extreme temperature shifts.

While some of the ice coating its north pole is water ice, much of it is carbon dioxide. Even on Earth, carbon dioxide never passes through a liquid state but sublimates directly into gas. Since Mars’ weak atmosphere doesn’t provide enough pressure to maintain liquid water, that gas doesn’t just bubble up through melted ponds, it destabilizes entire glacial structures.

So far, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) hasn’t caught any avalanches mid-fall this year. But in 2015, the MRO snapped a photo of a six-meter cornice in freefall over a scarp. It appears above as our lead image.

Geyers erupt across the Planum Boreum

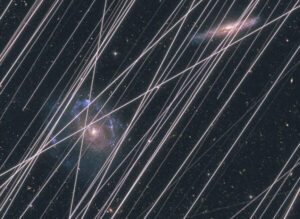

If sublimated carbon dioxide can’t escape through cracks in the ice, it builds up. When the pressure exceeds the weight of the ice, the gas jettisons everything above it and escapes into the atmosphere as a geyser. But the Planum Boreum, or northern polar plain, isn’t just covered in ice. The frost is mixed in with sand and dust. That creates dramatic images like this recent one from the MRO, where geysers leave darkened fans across the frosty surface.

The dark trails in this image are formed by geysers that erupt from the ice and leave dust in their wake. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Melting ice reshapes the landscape

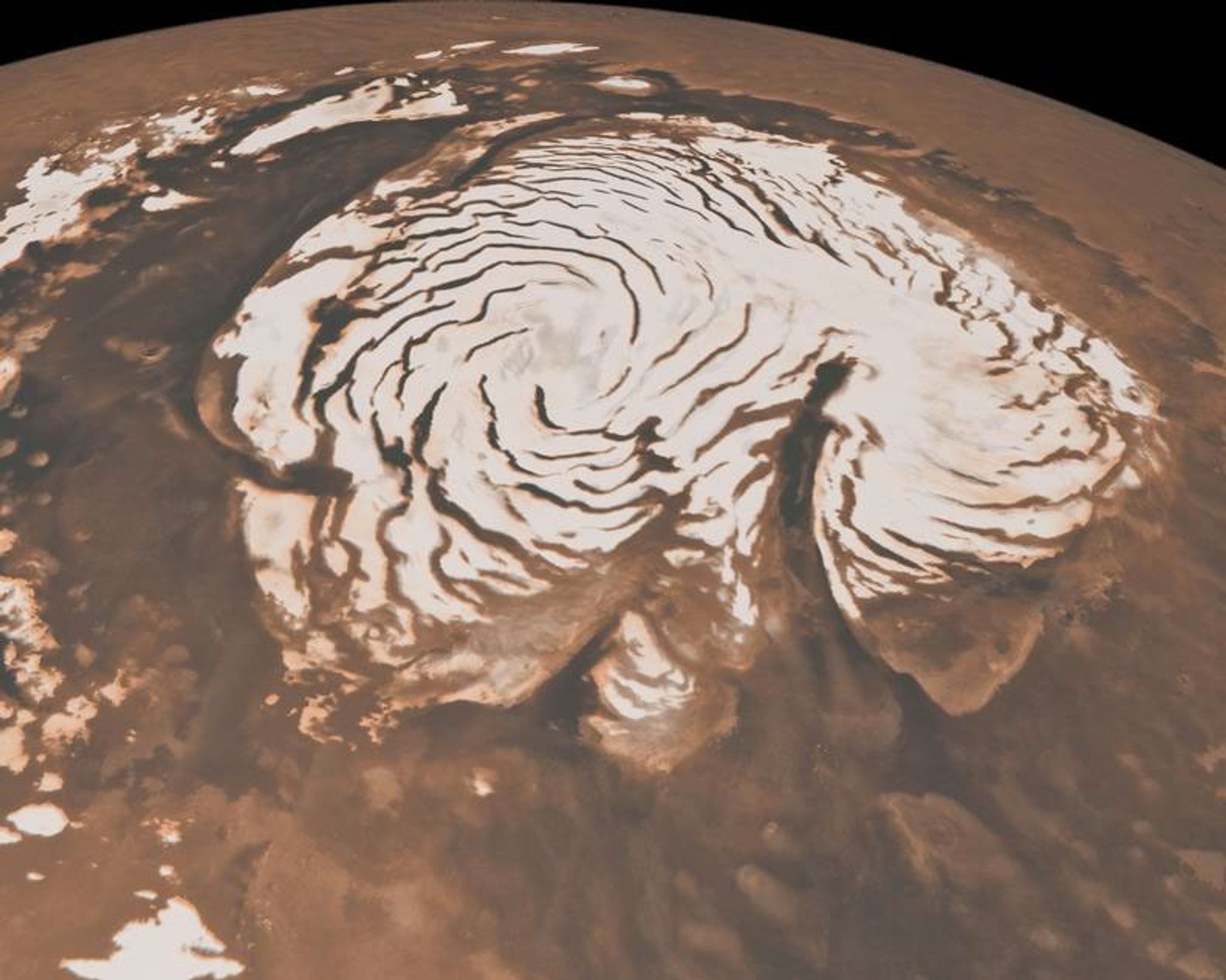

In Antarctica, glacial retreat driven by global warming has revealed permanent troughs in the ice. The legacy of long-ago ice erosion, these pale in comparison to the troughs spiraling across the northern ice cap of Mars. Every spring, the sublimated carbon dioxide forms winds, which gain speed as they propel their way down the labyrinthine corridors. They also rocket up in temperature, melting the walls of the troughs a little further each year.

The dark lines across the ice cap are troughs formed by hot winds, while the thicker band at the bottom right is a deep canyon. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

On Earth, winds like these mainly occur as cold air flows down icy slopes, such as in Antarctica and Greenland. They’re called katabatic winds. On Mars, they have thousands of kilometers of spiral troughs in which to gather power. They blast the sandy surface of the surrounding plains with enough force to shift entire sand dunes. These dunes are especially vulnerable in the spring because their frost layer has melted, as captured by the MRO on camera.

Come autumn, when the carbon dioxide frost starts to settle on the ice fields once more, the new progress of the glacial canyons and dunes will freeze in place. Mars then waits for the next thaw.

Each dark spot is a dune moving across the Martian plains. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona.