Last week, a magnitude 7 earthquake ripped through the Hubbard Glacier, on the Alaska-Yukon border. Now, fieldwork by the Yukon Geological Survey (YGS) has revealed localized avalanches and serac falls. The reaction of the Hubbard Glacier to this earthquake offers warnings to mountaineers climbing on a warming planet.

2025’s earthquake of the year

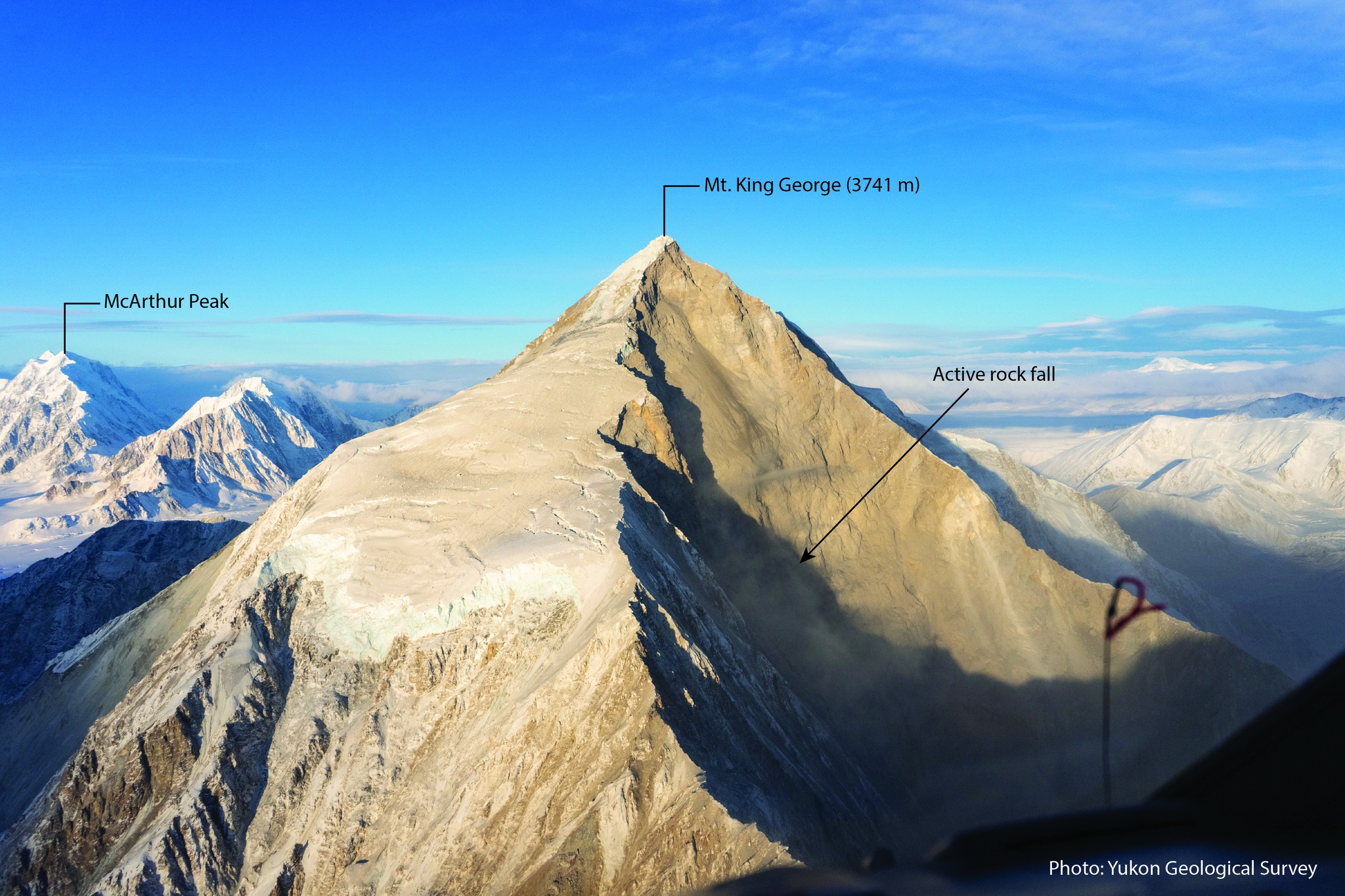

The earthquake originated near Mt. King George, where rockfall and avalanches are visible by eye. Photo: YGS

If it occurred in a densely populated area, the 2025 Hubbard Glacier earthquake could easily have killed thousands of people. Instead, it killed no one. In the mountaineering off-season, the American Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and the Canadian Kluane National Park lie abandoned by humans. Territorial lines notwithstanding, they both sit on the Hubbard Glacier, a roughly 100-km stretch of ice beginning at Mt. Hubbard and ending at Disenchantment Bay.

The recent earthquake struck a mere five kilometers under the surface of the ice and reached 7 on the Richter scale. Earthquake magnitudes are measured on a logarithmic scale, so a 7th magnitude earthquake shifts the ground 10 times more than a 6th magnitude, and so on. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake, for instance, which remains the deadliest in United States history, probably had a magnitude of about 7.9.

Cause not clear

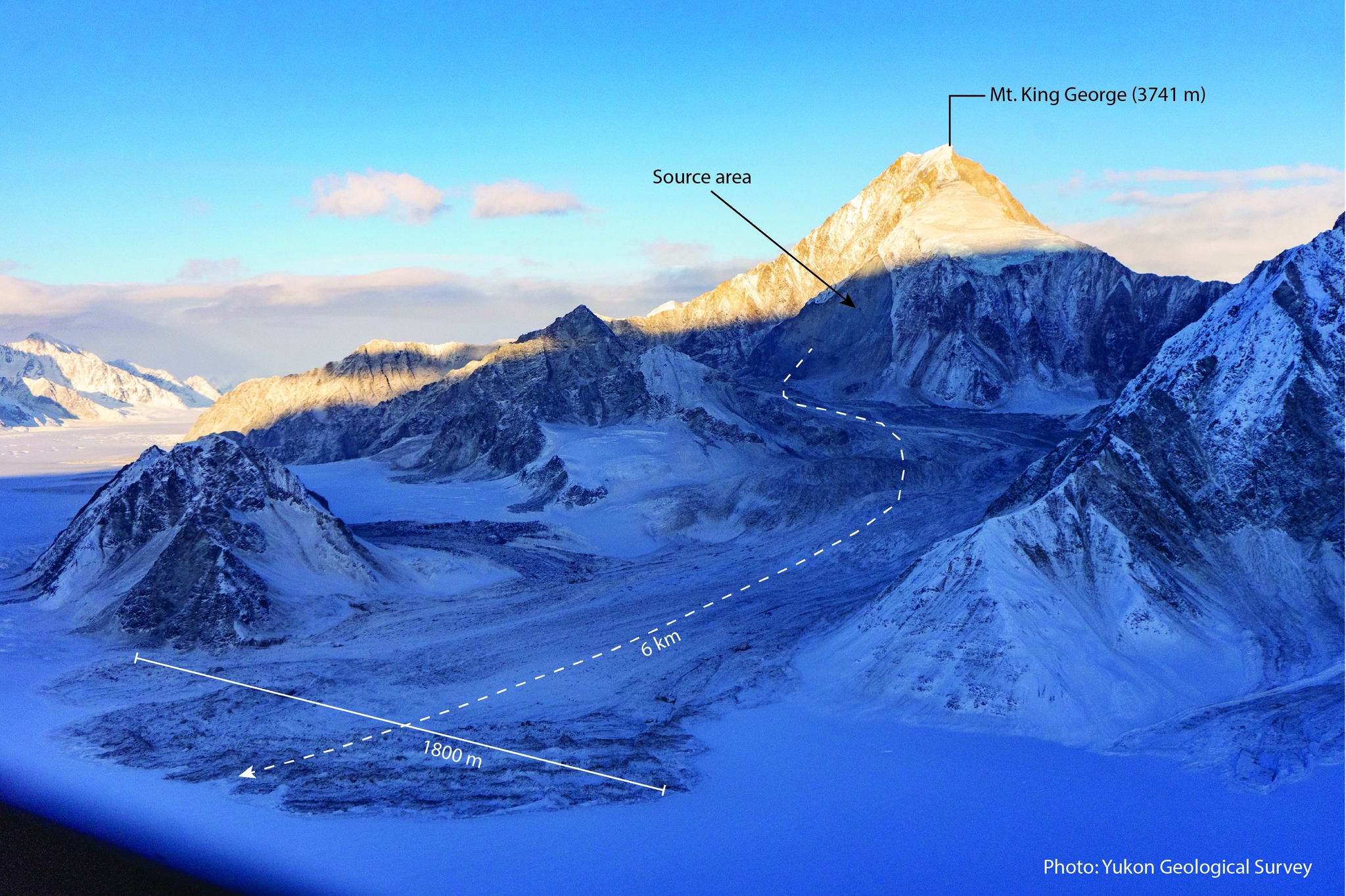

The YGS found the remnants of numerous avalanches near the epicenter. Photo: YGS

Understanding how and why an earthquake happens takes rapid follow-up. Much of that comes from local witnesses via systems like Did You Feel It? Their reports help pin down the epicenter of an earthquake. If the aftershocks all trace a line, they can even identify the fault line responsible. But in the case of the Hubbard Glacier earthquake, aftershocks clustered along a 65km blob, rather than a clean line neatly defining where the fault runs.

There are many potential explanations for this, as outlined in this brilliant write-up. One is that multiple mechanisms triggered this earthquake, leading to smaller earthquakes along other fault lines nearby. These mechanisms can include one plate sliding next to the other, one plate sliding under another, or more exotic events like magma bubbles.

Another possibility is that Hubbard Glacier’s placement along a geological transition zone — from classic plate shifting to the north, to subduction of one plate under another in the south — leads to messy, chaotic fault behavior. And finally, it’s also possible that some of the aftershocks were not earthquakes at all, but rather local icequakes.

New results from the Yukon Geological Survey

A view of Mt. King George with the most rockfall activity. Photo: YGS

The YGS posted preliminary results of their follow-up survey on Facebook. In that post, they state that the inciting event was one tectonic plate sliding two meters relative to its neighbor all at once. This is a significant amount of fault slip, but the team did not locate any places where the ground had ruptured.

Their results don’t offer conclusive answers regarding the clumpiness of the aftershocks. But whether or not the earthquake triggered icequakes, it certainly disrupted the glacial environment around 3,741m Mt. King George at the epicenter. When the YGS team arrived in the area shortly after the earthquake, they found dust hanging in the air from recent rockfall.

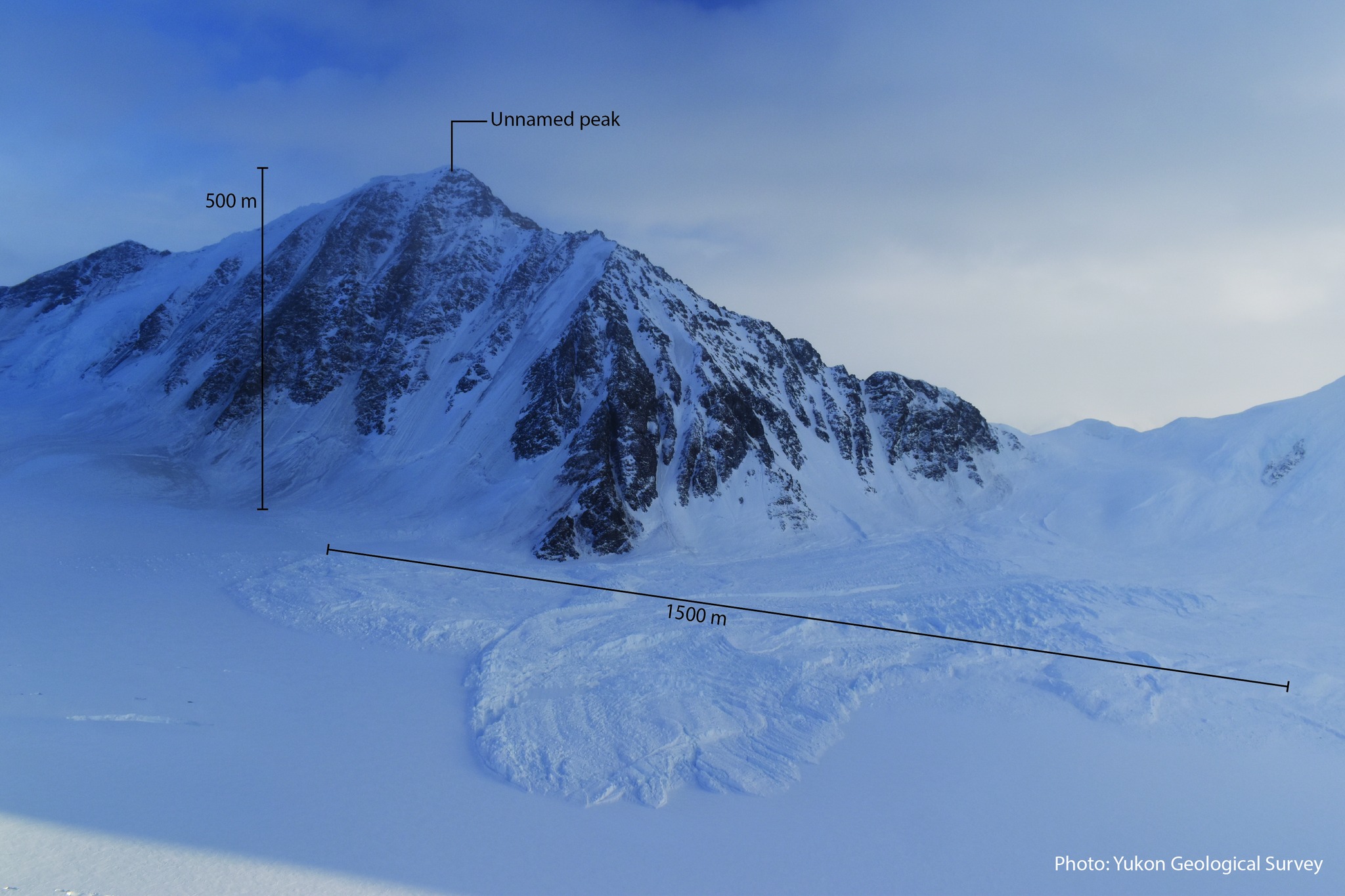

Radiating out from the epicenter, they found numerous snow and ice avalanches, as well as evidence of recent serac falls. But the damage on Mt. King George was most intense.

“It is fortunate that this event did not occur during mountaineering season, as earthquake-triggered serac falls and avalanches have caused fatalities in the past,” they wrote. “The damage to ice in the region and persistent rockfall from landslides scars may pose new additional hazards for mountaineering and skiing expeditions in the area.”

Threat to mountaineers

Serac falls amid an ice avalanche on the Hubbard Glacier. Photo: YGS

The reaction of glaciers to shallow earthquakes is a pressing issue for mountaineers as global temperatures rise. When glaciers melt, the water runs downstream and rejoins the sea. Without the weight of ice on top of it, the Earth’s crust rises. This process, known as isostatic rebound, is also responsible for some of Everest’s current upward growth.

Isostatic rebound has been occurring gradually over the last 20,000 years, since the end of the last Ice Age. It causes earthquakes worldwide, some of which trigger avalanches. Human-induced climate change compounds this effect. With glacier melt accelerating at unprecedented rates, low-level seismic activity seems to have increased beneath the Greenland ice sheet.

Geologists and glaciologists can use events like the Hubbard Glacier earthquake to better understand the seismological warning signs for ice and snow hazards. Potentially, this information could be incorporated into mountaineering ventures the same way that weather forecasts currently are. But right now, the YGS has issued a call for athletes to help out scientists, rather than the other way around.

“If any mountaineers or skiers have photos of Mt. King George before these slides, we would love to hear from you! Pre-event photos will help us estimate total landslide volumes. Please send any relevant photos to geology@yukon.ca.”