Want to learn to talk to a beluga? Better learn to reshape your head.

Ok, it’s not exactly as simple as that — you’d need a “melon” to perform the technique, and you’d need to be one of the rare species besides belugas who are able to control their physical shape.

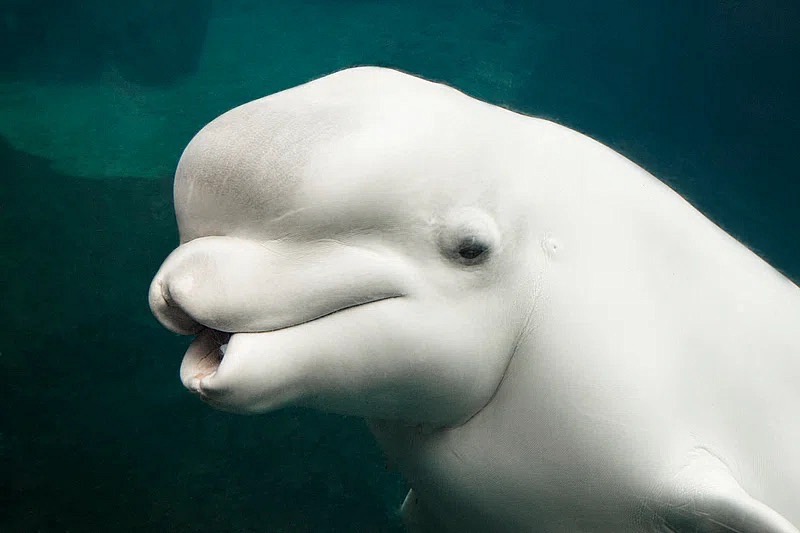

The melon is a bulbous frontal organ present in all toothed whales and is vital to cognition. In the journal Animal Cognition, a recent study determined that beluga reshape this organ at will in order to communicate with others.

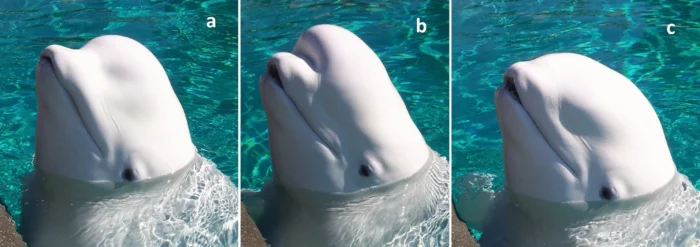

A trained beluga demonstrates the ability to voluntarily change the shape of the melon. Photo: Richard et al

Sending signals

The finding could be key to better understanding whale social behavior, and even the evolutionary roots of language. While many other species can relay signals with facial expressions, whales’ facial tissue is generally too thick to reveal muscular contortions — even if the whale is making them.

The study found that the beluga workaround is unique among cetaceans. It’s also highly complex. Observing 55 belugas at Connecticut’s Mystic Aquarium and Canada’s MarineLand, the researchers counted over 2,600 melon gestures during more than 250 hours of study. While they watched, they noticed that the whales gesticulated with special fervency while a peer was paying attention.

“Melon shapes occurred 34 times more frequently during social interactions (1.72 per minute) than outside of social interactions (0.05 per minute),” the study said. The shapes occurred “within the line of sight of a recipient 93.6% of the time.”

Researchers have observed melon shaping in belugas for a long time. However, the theory that it’s a social behavior builds on previous consensus that the whales used it only for echolocation. But this acoustic function evidently doesn’t tell the whole story.

Foundations of language?

Belugas create intricate social networks, with various forms of sexual signaling and group activity. Within a framework like that, lacking the ability to make faces would be an understandable disadvantage.

Problem solved.

The study codified five main melon shapes: flats, lifts, pushes, presses, and shakes. Footage shows how the shapes shift during social interactions. These interactions ranged from playful and amorous (“genital presents”) to aggressive — biting or “raking” each other with their teeth.

Males made shapes more than three times as often as females, and the researchers correlated some shapes with specific goals. Belugas “pushed” their melons especially while antagonizing each other. And “shakes” aligned strongly with courtship acts.

The research group noted one of its study’s strengths is the belugas’ aquarium habitat, where it’s easier to gather information about specific animals’ long-term behavior patterns, sexual preferences, etc. However, it’s also a shortfall. The study admits the small sample size and artificial environment leave many questions unanswered.

Still, the work opens the door to exploring if and how belugas socialize according to goals. This behavior is the basis of intentional communication — a tenet of human language.