Today is the 66th anniversary of the disputed — many would say discredited — first ascent of Patagonia’s Cerro Torre by Cesare Maestri and Toni Egger.

The undisputed first ascent came many years later, in 1974 rather than 1959, when Italians Daniele Chiappa, Mario Conti, Casimiro Ferrari, and Pino Negri topped out via Cerro Torre’s west face. But Maestri’s and Egger’s 1959 ascent, though widely considered false, deserves to be part of the peak’s climbing history.

Cerro Torre and Fitz Roy from above. Photo: NASA

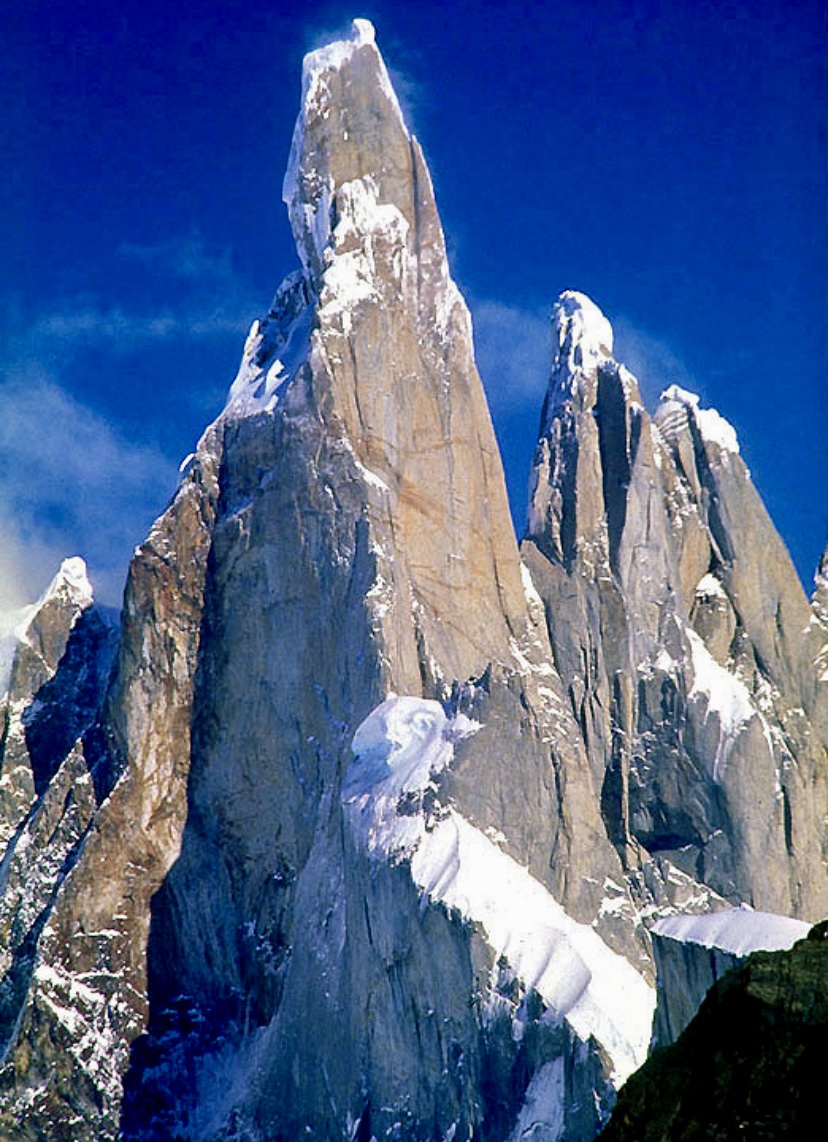

Cerro Torre, the impossible mountain

At 3,133m, Cerro Torre is on the border dividing Argentina and Chile, west of Fitz Roy. Fitz Roy (3,405m ) was first climbed on Feb. 2, 1952 by Lionel Terray and Guido Magnone of France.

The towers are the preserve of the world’s best mountaineers. Fast-changing weather conditions, vertical walls, and demanding lines make them incredibly difficult.

Cerro Torre. Photo: Davide Brighenti

When Terray saw Cerro Torre from Fitz Roy, he was amazed by its beauty and described it as “an impossible mountain.” Naturally, this excited the climbing community.

“Unlike other storied alpine ranges, the challenges of Patagonia have nothing to do with altitude…nowhere on Mount Everest or K2 — not even on their hardest routes — nor on any of the alpine ice routes in the Alps, will you find such sustained vertical climbing as on Cerro Torre’s ‘easiest’ route,” Kelly Cordes wrote in his book The Tower.

Its difficulty, along with its gripping shape that looks like it is giving the finger to all who might dare to attempt it, has attracted climbers for decades.

Cerro Torre, 1958

At the beginning of 1958, two parties intended to make the first ascent of Cerro Torre.

One group, led by Bruno Detassis and including Cesare Maestri and Italian-Argentinian Cesarino Fava, planned to climb the east face. The other group included Carlo Mauri and Walter Bonatti. They wanted to climb the west side of Cerro Torre.

The teams were rivals and would not join forces.

Bonatti and Mauri made a bold attempt on the west face and managed to climb half the route. They retreated roughly 450m below the summit.

In the end, Detassis’ party didn’t attempt the east face, considering it too dangerous. Maestri did not want to give up, and although he accepted the leader’s decision, he started to plan a return to Cerro Torre.

Cerro Torre’s summit area. Photo: Ty Lekki

The 1959 claim

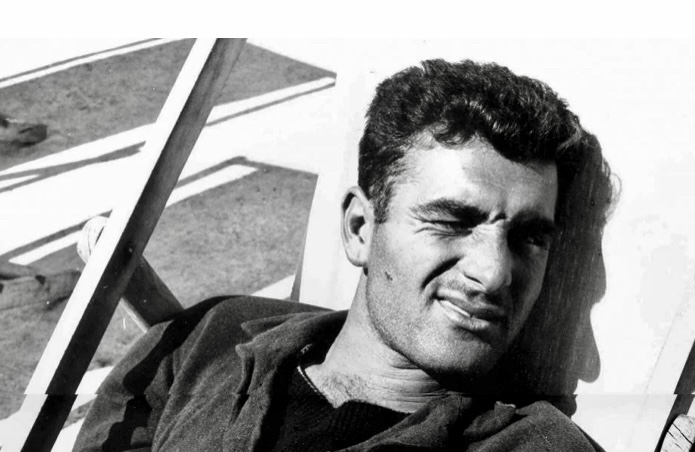

In January 1959, Maestri was ready to return. Maestri was one of the best rock climbers of his era, famous for bold solo ascents, often without a rope. His partner was Toni Egger of Austria, an elite ice climber. Cesarino Fava would support them. They also employed a small group of young climbers to help carry loads to their camp.

Maestri and his two partners targeted a route that would start from Cerro Torre’s east side, continuing via the north face and the north ridge of the tower.

Fava retired from the climb on the first section of the route, but Maestri and Egger continued. At the end of January, a week passed with no news on their whereabouts.

After six days, Maestri returned alone. He told Fava that he and Egger summited Cerro Torre on Jan. 31, but an ice avalanche swept Egger away soon after. According to Maestri, Egger had the camera that contained the summit photos.

Egger, Maestri, and Fava. Photo: Infobae

Doubts emerge

The first ascent was major news, but doubts soon started to emerge.

Maestri’s testimony and description of the ascent featured many contradictions. Several years later, other climbers approached the route and didn’t find any bolts, pitons, or fixed ropes. Supposedly, Maestri had left bolts in the wall.

Maestri continued to insist that he had summited Cerro Torre. In 1970, he returned wth Ezio Alimonte and Carlo Claus to attempt the southeast ridge. Using a huge, gasoline-powered air drill compressor, they put 360 bolts into the wall. They reached a point just below the summit mushroom, 40m-60m below the top. However, Maestri considered this the summit, stating that the snowy summit mushroom was not part of the mountain. They left the compressor on the mountain, and their route is now called the Compressor Route.

The first climbers to make a complete ascent of this route were Steve Brewer and Jim Bridwell in 1979.

Jim Bridwell on the Compressor Route. Photo: Jim Bridwell

Garibotti’s report

In 2004, Patagonian climber Rolando Garibotti published A Mountain Unveiled: A Revealing Analysis of Cerro Torre’s Tallest Tale. He examined all the available details: Maestri’s and Fava’s accounts, the fact that no one subsequently found any trace of the trio’s climb beyond 300m on the wall, and the doubt expressed by other climbers.

“Taking all of the factors into account, Maestri’s and Fava’s descriptions of what took place in 1959 are completely unreliable,” Garibotti concluded.

Ascending the north face

In 2005, Garibotti, Alessandro Beltrami, and Ermanno Salvaterra became the first team to climb the north face. They named their route The Ark of the Winds. Their route was on the same face that Maestri claimed to have climbed. According to Garibotti, they found no evidence of the 1959 team and the face proved very different from Maestri’s descriptions.

Cesare Maestri. Photo: P. Melucci

In July 2006, Ermanno Salvaterra published a detailed report on The Ark of the Winds.

“I am a trusting person. For a long time, I defended Maestri, Egger, and Fava. I had known Maestri for a long time, and I admired his strength and stubbornness. It hadn’t occurred to me yet that those very qualities, combined with his drive to succeed, might overpower his ethics,” Salvaterra wrote.

Reinhold Messner also had doubts about the 1959 claim. He asked Maestri to meet and clarify what happened. But Maestri and Fava were angry and did not want to meet. The three men only connected via a few letters.

The dispute continues

The dispute continued with a series of counter accusations, via letters and public statements made by Maestri and Fava, who kept claiming the first ascent.

The Ark of the Winds was proposed for a Piolet D’Or, but Maestri and Fava wanted the 2005 line to be called a repetition.

“I claim, once again, the right to respect. [Regarding] statements that are biased and harmful toward me, and offensive to the memory of Toni Egger, I take advantage of the occasion to demand that [no one] seeks to discredit my word, speculate out of opportunism, and intentionally spread falsehoods, slander and distorted versions of what I have said, confirmed and written several times,” Maestri wrote in a statement published by Desnivel.

“I do not doubt that Toni Egger and Cesare Maestri reached the summit of Cerro Torre,” Fava said in a separate statement.

Cesarino Fava and Cesare Maestri. Photo: Cultura de Montania

Evidence

In 2015, Garibotti, with the help of Kelly Cordes, published a new report. They examined a photo published by Maestri, pinpointing where it was shot. Garibotti concludes that in 1959, Maestri and Egger were on the western flank of Perfil del Indio, on the opposite side of the tower they claimed to have climbed.

Garibotti’s report was titled Completing the Puzzle.

Rolando Garibotti, left, and Ermanno Salvaterra at the first bivouac on the route The Ark of Winds. Photo: Alessandro Beltrami

After the extensive research work by Garibotti, we can conclude that Maestri’s claim was indeed false. The evidence suggests that the 1959 ascent is not just “disputed” but a hoax. Maestri has never shown any evidence of their ascent nor presented any counterarguments to criticisms leveled by people like Garibotti. Maestri died in 2021, still insisting they summited.

A map showing where Garibotti concluded Maestri and Egger climbed. Photo: Rolando Garibotti

Of course, Maestri and Egger were much more than the Cerro Torre tale. They were great climbers, and we will discuss their climbing careers in another story.

Below is an interesting interview with Messner, who speaks about Cerro Torre and Maestri.