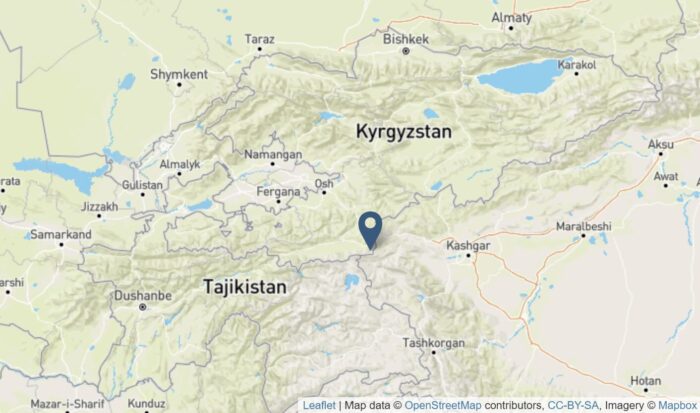

If single unclimbed peaks are hard to find in this era of online beta, imagine an entire range where no climbers have set foot ever before. A young team from Britain and Ireland has done just that. Their first ascents took place in the Nura Valley, in the Alay region of southern Kyrgyzstan.

Rather than extremely technical routes or big faces, the interest of this expedition lies in their exploration of unknown mountains. The young team included Joe Collinson, Maria Koo, and Lawrence Luscombe of the UK, and Orla O’Muiri of Ireland. Supported by the Mount Everest Foundation (MEF), the team did remarkable research to compile all the details, maps, images, useful addresses, notes on gear, and tips for future climbing expeditions. Their detailed report is available here. However, here’s a summary.

Location of the Nura Valley in southern Kyrgyzstan. Map: Sapar 2025 Expedition

How to get there

The team’s first goal was to find a way to access the valley across rivers, moraines, and glaciers. Then, if successful, they needed to climb one of the area’s intriguing 5,000’ers, none of them previously summited.

They approached the area initially by truck, then switched to horses, and finally trekked into the Nura valley. After crossing a river, the team established its base camp on a flowery alpine meadow.

Approaching the Nura Valley. Photo: Sapar 2025 Expedition

One more crossing of the Nura River, which was only possible early in the morning before the current grew too strong, led them to moraine and their advanced base camp.

The climbs

As in other ranges last summer, including the Karakoram, the weather had been extremely hot for several weeks before they arrived. The snowline was a lot higher than they had expected, and there was not that much snow to ski down the peaks, as they’d intended.

“North-facing slopes had snow to around 4,000m, and south-facing, non-glaciated peaks were completely bare as high as we could see (4,560m),” they reported.

However, they noted the area could offer excellent skiing for those coming earlier in the year.

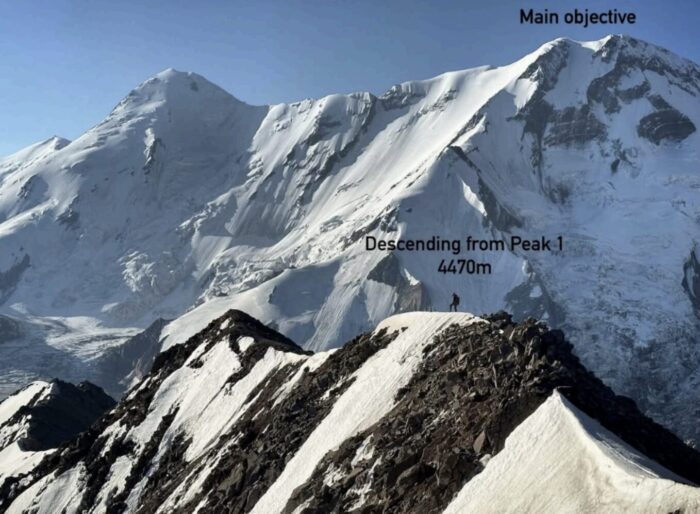

Skiing was forgotten, and instead, the team headed for the north faces of peaks on the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Their first climb was the enchainment of four neighboring 4,500m peaks. They climbed the first peak from its west side, with the first 500m of altitude done on dry terrain and then mixed ramps up to 50 degrees. They then followed the ridge, at times quite sharp and exposed, to the east that took them to three more summits.

View along the ridge traverse heading east, taken from the summit of the first peak of the enchainment. Photo: Sapar 2025 Expedition

By then, the climbers had chosen the expedition’s main objective: an unnamed peak marked as 5,670m high. As bad weather approached, they retreated to base camp and waited for a suitable weather window.

Gear stolen

When forecasts announced a four-day period of good weather, they returned to their advanced base camp to find their equipment gone.

“All that remained were three snow stakes and one ice axe,” they said.

Locals later told them that the spot was a common smuggling pass between China and Kyrgyzstan.

“It is our working theory that two smugglers must have taken our bags into China,” they wrote. “Each bag weighed 25-30kg, so it is somewhat impressive they took the bags in their entirety, in addition to whatever they were smuggling.”

They decided to pool all their remaining gear and attempt the climb anyway. They left at midnight for the base of the mountain, where they had planned to climb “an obvious and aesthetic 1,500m line cut into the lower face before joining the prominent north ridge via a narrow crux gully, before the final ridge, which led directly to the peak’s double summit.”

Climbing on ice ramps at dawn. Photo: Sabar 2025 Expedition

Too risky

The team climbed on glacial ice and passed the most difficult section, a 60º couloir that led to a plateau at 5,000m. This left only the final, lower-angle snow slopes and the 600m or so to the summit.

By then, unfortunately, the sun was hitting the slopes, making the snowpack too unstable to risk the last section. Making seven rappels, they retreated to the bottom of the peak.

Afterward, the climbers made a last-day attempt on a 4,780m peak. They reached a col after climbing through the night, but the weather had deteriorated, and visibility was nearly zero as the sun rose, and they retreated.

“Despite only succeeding on their first route, the expedition was able to gather valuable information on the valley, including details of the approach and several potential routes,” the Mount Everest Foundation noted.