Mount Waddington, an infrequently climbed peak in British Columbia’s rugged Coast Mountains, was initially known as the Mystery Mountain because of its remoteness. This is the story of early expeditions to this fortress of ice and stone.

Hard to reach

At 4,019m, Mount Waddington is the highest mountain entirely within the Canadian province of British Columbia. Taller peaks, such as Mount Fairweather and Mount Quincy Adams, lie on the British Columbia–Alaska border.

Approximately 300km northwest of Vancouver, Mount Waddington is surrounded by deep valleys and glaciers. Even approaching it is a great adventure over extreme terrain, ice fields, and difficult peaks. Early explorers often compared the area to the Himalaya, and many films set in the Himalaya were filmed in the Waddington Range.

The Waddington Range. Photo: Kevin Teague

Discovery

Don and Phyllis Munday were a renowned Canadian mountaineering couple with experience in the Pacific Northwest, Rockies, Selkirks, and the Coast Mountains. Between the 1920s and the 1940s, the Mundays climbed more than 150 peaks, with over 40 first ascents. In 1924, Phyllis became the first woman to summit 3,954m Mount Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies. She climbed with Annette Buck, and Don Munday also summited.

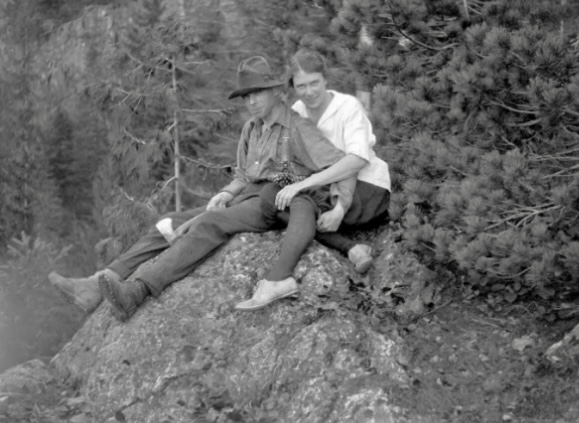

Don and Phyllis Munday. Photo: Cheknews

In 1925, Don and Phyllis Munday spotted a huge peak from Mount Arrowsmith on Vancouver Island. It is unclear if this was Mount Waddington, but their observation sparked exploration of the Waddington Range. The Mundays were the ones who dubbed that distant peak Mystery Mountain.

Authorities officially named Mount Waddington in 1928, following the recommendation of the Mundays. Alfred Waddington was an industrialist who advocated for a road and railway through the region.

Mount Waddington. Photo: Wikipedia

The Mundays’ attempts

For over a decade, the Mundays made several attempts to climb Mount Waddington, the most important of which was their 1928 expedition.

The couple began from the Franklin Glacier on the southwest side and ascended via the northwest ridge. On July 8, they reached the lower northwest summit at around 4,000m. There, they concluded that reaching the main summit would be too dangerous.

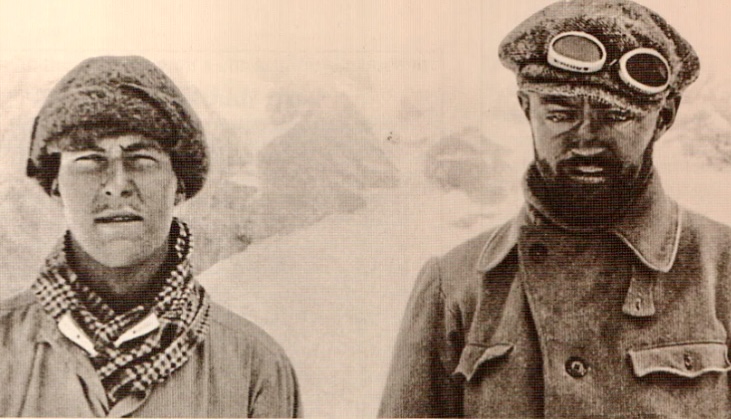

From the 1928 Munday expedition. Photo: Don and Phyllis Munday

Tragedy in 1934

In the summer of 1934, a party from British Columbia, including Neal Carter, Alan Lambert, Alec Dalgleish, and Eric Brooks, likewise approached the mountain via the Franklin Glacier. They targeted a couloir on the south face leading toward the southeast ridge.

They reached 3,700m, but the expedition was called off after Dalgleish fell to his death on June 26. The accident happened only three days after they had established base camp.

Other attempts

In the same year, a Winnipeg-based team attempted to ascend via the Tiedemann Glacier and the northwestern flank. The party turned around 180m below the summit because of bad weather on June 28, 1934.

In 1935, climbers from California made three attempts from base camp at Dais Glacier, including two tries via the South Face. They failed to summit because of bad weather and technical difficulties. Their highest point was around 3,500m. During a third attempt, two climbers reached the northwest summit, first climbed by the Mundays in 1928.

According to climber Fred Beckey, there were 16 attempts on Mount Waddington before its first ascent. However, Beckey didn’t list all 16 attempts in his writings.

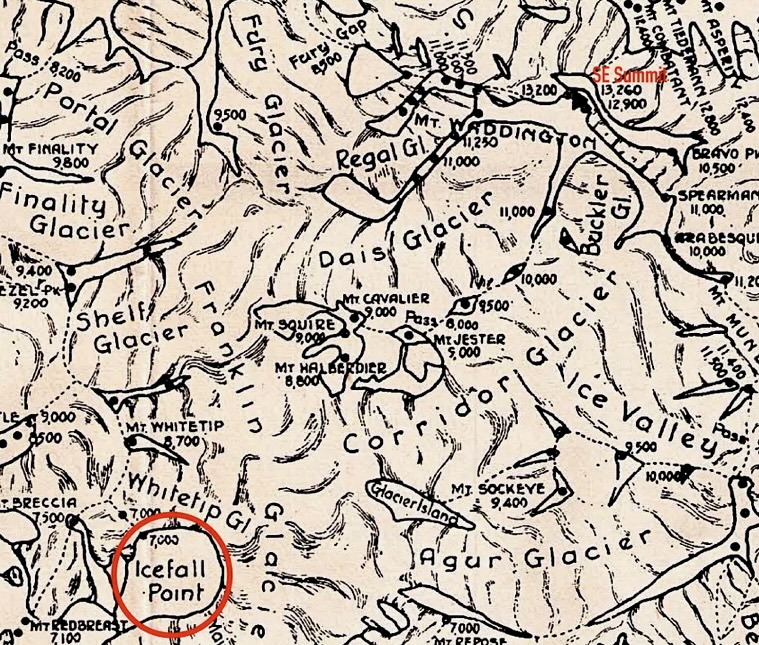

A map of the area showing the glaciers and Icefall Point (marked in red). Photo: John Middendorf

Fritz Wiessner and his small team

In the spring of 1935, alpinists Bill House, Elizabeth Woolsey, and Alan Wilcox started to plan an expedition to the Coast Range. A year later, German-American Fritz Wiessner joined the trio and led the small team to attempt the still-unclimbed Waddington in the summer of 1936.

Wiessner’s team learned that the British Columbia Mountaineering Club (BCMC) and the Sierra Club of California had joined forces. As a combined party, they were planning to climb Mount Waddington at around the same time.

According to Bill House’s report in the American Alpine Journal, after a meeting between the leaders of both groups, they agreed that the mountaineering clubs would attempt the climb first. Both teams targeted the South Face, with the BCMC-Sierra Club team setting up base camp at Icefall Point on the Dais Glacier.

The BCMC-Sierra Club team did not succeed. They couldn’t find a viable route up the face on difficult terrain.

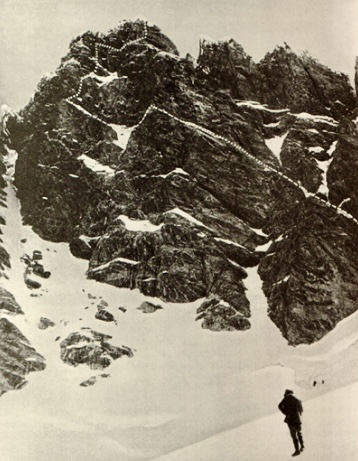

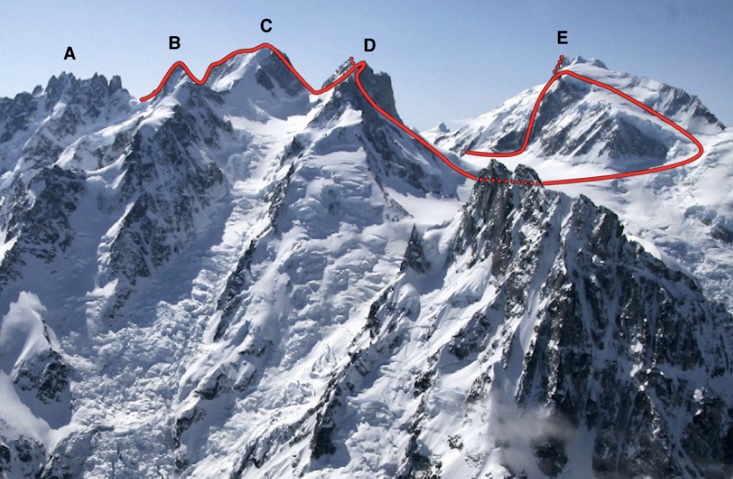

The first ascent route of 1936. Photo: John Middendorf

The South Face

The South Face, broken up by three couloirs, is known for poor route conditions and falling ice. An 800m granite wall of complex rock, snow patches, narrow couloirs, and mixed icy sections complicate the climb.

After a challenging approach via the Franklin Glacier, Wiessner’s team established their base camp on July 14, 1936. Like the BCMC-Sierra Club team, they chose Icefall Point (1,787m) on the upper Dais Glacier. Icefall Point is a spur of heather-covered rock. According to House, it’s the last place where a party can find firewood and running water.

Woolsey and Wilcox helped carry loads to camp but wouldn’t join the summit push.

On July 20, Wiessner and House started up via the left branch of a couloir between the main summit and the northwest peak. They eventually retreated because of poor rock conditions.

So instead, they then headed to the right of the South Face. By 2:45 am on July 21, Wiessner and House were on their way toward the summit from their high camp. They climbed the 305m upper section of ”forbidding-looking” rock in 13 hours.

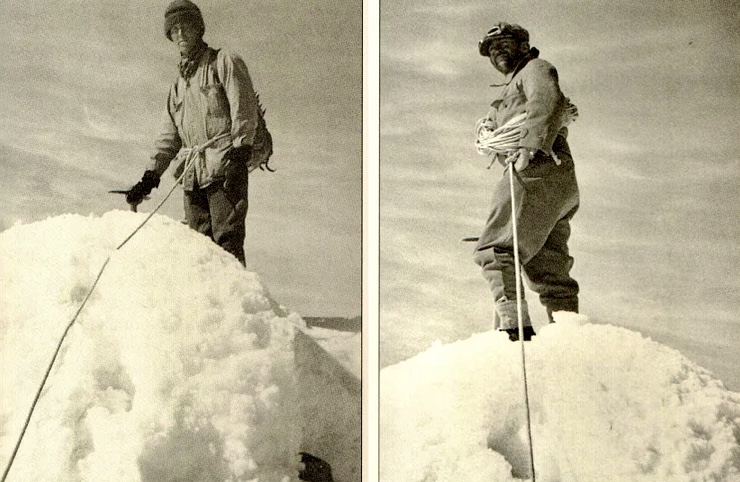

Bill House and Fritz Wiessner on the summit of Mount Waddington.

The summit

On July 21, Wiessner and House topped out.

”It is a hopeless task, as every mountaineer knows, to try to do justice to one’s feelings at the summit of a difficult peak. Probably relief is the most dominant one at the time,” House recalled.

On the top, they left a summit register in a waterproof match can. Wiessner and House descended by the same route and reached base camp on July 22 at 2:00 am. Their round trip took just over 23 hours.

It was a lightweight, alpine-style ascent using minimal, rudimentary gear (18 pitons). This contrasted with earlier expeditions, which tended to be large, complex affairs.

Wiessner and House demonstrated that the ”unclimbable” could be climbed. The 1936 first ascent marked the culmination of years of exploration and ticked off one of the last major unclimbed summits in North America.

House and Wiessner after descending from Mount Waddington. Photo: Betty Woolsey

Two teens target Mount Waddington

In 1942, six years after the first ascent, 19-year-old Fred Beckey and his 16-year-old brother Helmy Beckey decided to climb Mount Waddington’s South Face. With World War II underway, resources were few, and the Beckey brothers had no sponsors or porters, only their parents’ vague approval.

“Long behind seemed the months of preparation, conditioning climbs, and first ascents made in the Northern Cascades of Washington in June,” Fred Beckey wrote.

The summit tower of Mount Waddington. Photo: Colin Haley

With climber Eric Larsson, the brothers started their multi-stage journey from Seattle. Traveling via bus to Vancouver, then steamship to Knight Inlet, and finally via a smaller boat to the Franklin River delta, they approached overland on foot.

After several days of travel from the coast, they reached the Franklin Glacier. Crossing required 32km of unsupported glacier travel. The approach added more than 2,000 vertical meters and weeks of effort to their adventure.

On the second day on the Franklin Glacier, Larsson fell ill and had to quit. The Beckey brothers continued and established base camp on the glacier below Waddington’s southwest face on July 20.

The ascent

The brothers decided to attempt the South Face route slightly to the right of the chimney climbed by Wiessner and House.

They traversed the glacier, navigating crevasses and icefalls to reach the base of the face. They carried minimal gear and moved in a lightweight style. Then they climbed to a higher camp to position themselves for a summit push. That process took a couple of days in complex terrain and worsening weather. When conditions allowed, they moved up quickly.

Mount Waddington. Photo: Peakvisor

On the upper face, Fred Beckey changed to tennis shoes with felt pullovers to mount the rock slabs.

“The pullovers adhered well to the rock when wet and could be removed quickly for more friction on dry rock,” Fred Beckey wrote in his report. (The term ”pullover’ refers to an improvised covering for the shoes.)

As they climbed, ice fragments broke off the summit ridge and thundered down the chimneys to their left.

On August 8 at 8:30 pm, Fred and Helmy Beckey topped out on the main summit. It was one day after Helmy’s 17th birthday. On the summit, they found Wiessner and House’s match-can register. It was the second ascent of the mountain.

During the descent, Helmy was hit on the knee by a rock as they descended into the gap between the northwest and the main peaks.

“This was Helmy’s birthday present, donated by Mount Waddington,” Fred said. ”Any hope of reaching camp that night was gone because of a heavily bleeding cut.”

The next day, they continued their descent and reached base camp.

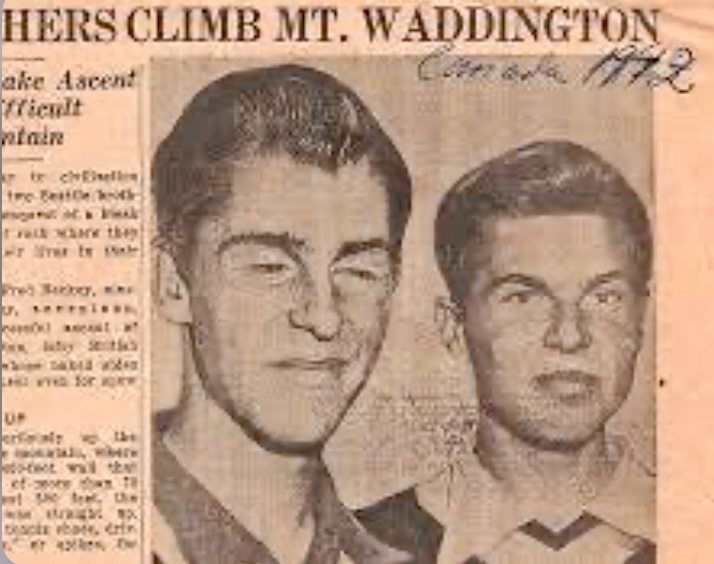

Fred and Helmy Beckey in a newspaper after the successful climb.

Legacy

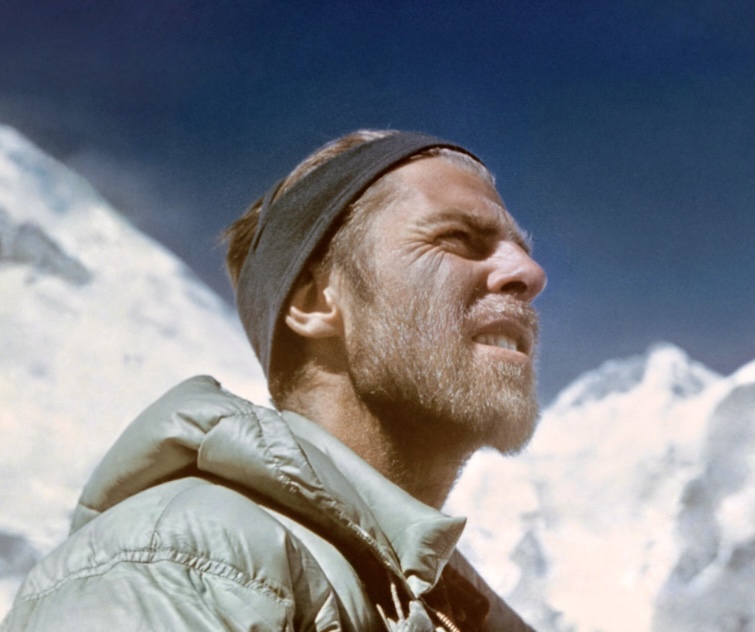

The Beckey brothers’ feat was outstanding. Fred continued his climbing career and made hundreds of first ascents in North America. He also wrote a dozen books, hundreds of climbing reports, and several climbing guides. He dedicated his life to mountaineering and died at 94.

Colin Haley, who in 2012 made the first solo ascent of Mount Waddington, wrote about Fred Beckey for the American Alpine Journal:

“Fred was without a doubt the most accomplished climber ever to come out of North America and is among the all-time greats, right alongside figures such as Riccardo Cassin, Hermann Buhl, Lionel Terray, Walter Bonatti, and Reinhold Messner.”

Colin Haley’s solo traverse of 2012. Photo: Colin Haley

In 1996, Fred Beckey, John Middendorf, and Calvin Herbert made the first ascent of a peak in the Cathedral Mountains in Alaska. They named it Mount Beckey.

We recommend watching the documentary Dirtbag: The Legend of Fred Beckey, by Dave O’Leske.

Fred Beckey in the early 1950s. Photo: Fred Beckey Archives