Under a blazing sunset in the Patagonian winter evening on September 19, Colin Haley stood on the summit of Fitz Roy alone.

Recalling the moment later, after the conclusion of a mind-bending solo effort that almost didn’t happen, he wrote that he “felt very, very far away from everything.”

Understandably so: No one had ever done what he’d just done.

That night, the American alpinist became the first climber to solo Fitz Roy’s “Supercanaleta” (1,600m, 5.9, WI4, M5-6) in winter. The iconic route charges the deep gash in the 3,405m tower’s West Face. The climbing is not overly difficult, but the route length and potential for rock and ice fall introduce serious overtones.

The West Face of Fitz Roy, and ‘Supercanaleta’. Topo: Rolando Garibotti

So do the last several hundred metres, where a series of gendarmes guard the summit.

If you want to know how gnarly the “Supercanaleta” can be — especially climbing it alone in winter — just ask Haley. As he wrote on his blog, he has tangoed with it several times throughout his long career, achieving varying degrees of success. He first climbed it 15 years ago, with Canadian alpinist Maxime Turgeon. That outing resonated in Haley’s memory due to a “miserable” forced bivy. But it didn’t stop him from making the second-ever solo ascent of the route two years later in 2009.

Finally, he speed-climbed it with Alan Wyatt in 2016, capturing the first one-day ascent of Fitz Roy in the process.

So Haley arrived for his objective this year on the “Supercanaleta” prepared, or as close to it as he could get. The psychological aspect of the challenge also weighed heavily on him. He was intimately acquainted with the grave consequences of a mistake.

“I probably know the route better than anyone, but nonetheless my most recent ascent was 6.5 years ago, and the route is 1,600m tall, so I hardly felt like I remembered it well,” he wrote on his blog. “Two other climbers have fallen to their deaths climbing solo on the route, and I have had the unpleasant experience of coming across both of their bodies, so the deadly consequences of making a mistake while soloing the ‘Supercanaleta’ are grimly seared in my memory.”

From Haley’s exhaustive account, it’s clear that the climb pushed him to the brink.

First try shuts Haley down cold

Haley arrived for the attempt in El Chaltén on August 29. Then he started ferrying loads up to Piedra Negra, where he would leave a gear cache for the push. He would speed solo the route, looking to climb and descend all 3,000+ metres in a day.

His first suitable weather window opened on September 12. Bitter morning temperatures hampered Haley while he kitted out, but he started up the “Supercanaleta” anyway.

For 300m, he climbed “easy” snow. Then the snow cover waned, revealing a skein of unyielding, gray ice.

“Despite being technically easy, all the hard ice made the couloir drastically more tiring and time-consuming than in typical summer conditions, when it is filled with snow and névé,” he wrote. “[Although] I wasn’t surprised by the difficult conditions, it wasn’t until 4 hours after crossing the bergschrund, and a humongous amount of front-pointing and axe-swinging, that I arrived to the Bloque Empotrado, and the start of the more technical climbing.”

Haley proceeded methodically to a key rappel location, arriving there at about 2:30 pm. He considered his options, but the promise of frigid overnight temperatures forced a retreat.

“With the winter temperatures, I knew that I couldn’t risk being high on Fitz Roy in bad weather. It was pretty clear that the only reasonable choice was to bail,” he wrote.

But because the evening sun was drenching the gully below, keeping it warm, there was no need to rush. So Haley maintained his post for a few minutes — and entertained enough existential dread to make him doubt whether he’d come back to try again.

“I spent 30 minutes pondering life, climbing, the people I love, soloing, ambition, risk, and the desire to stay alive. I felt as I have many times before, that what I was doing was ridiculous, and too stressful and scary to be enjoyable. Already before setting up the first rappel, I thought it was very unlikely that I would make another attempt. In fact, I concluded, once again, that it was time to put hard, solo alpinism behind me,” he wrote.

A long, nerve-wracking rappel ensued amid frequent rockfall. So did an arduous pack-out back at the gear cache, where snow blew so hard that it broke Haley’s tent poles and filled his jacket pockets. Finally, “torrential” rain soaked him to the bone on the hike out.

El Chaltén: regroup or retreat?

Haley was demoralized.

“It was particularly heinous because I hiked out with all my equipment and therefore a very heavy pack, confident not only that I wouldn’t make another attempt on the Supercanaleta, but that I wouldn’t do more solo climbing on the trip at all.”

Intent on some fair-weather sport climbing with his partner, Alisa Owens, he dumped his saturated gear in El Chaltén and tried to forget about the “Supercanaleta.”

Winter in El Chalten. Photo: Jose Galleguillo via Wiki Commons

But then the clouds parted, and he started to remember it. Haley recalled thinking about prominent German climber Reinhard Karl, who in 1982 endured an epic attempt so repugnant he buried his climbing gear in the snow and walked away.

Considering that and the improving weather, Haley thought he might not be so badly off, after all. A game familiar to many climbers thus began: rationalization and compromise.

“Just the day after returning to town, I started to think about the Supercanaleta again. I thought about how I could improve my strategy, and rationalized that it wasn’t so bad up there. It soon became clear that another spell of good weather, in fact, a much better spell of good weather, was on its way. Within a couple of days after returning to town, I began to pack and plan for another attempt.

“On the morning of Sept. 17, I was hiking back into the mountains.”

‘Frenzied’ climb, ‘anxious’ summit

Haley started up Fitz Roy under strikingly similar circumstances to his last attempt just five days before. He crossed the bergschrund at the head of the glacier around 7 am again — doing so because he knew the route would get afternoon sun. He found roughly equivalent conditions on the first 1,000m of climbing, though a little more snow adhered to the hard gray ice above.

Then he reached his previous high point 15 minutes earlier than he had before. Though he still felt intimidated, that night’s forecast gave him a better outlook for climbing the tricky gendarmes.

So he decided to go for it.

“I was in a sort of focused frenzy for this whole section of the climb, moving as fast as I felt I safely could, but having to take a lot of care in many places, and a lot of time in several places. On some sections, there was a bunch of rime plastered to the rock, which made progress slow, but in other places, the rock was nearly bare, which was very advantageous.

“As the sun was dipping to the west it was filtered through low clouds above the South Patagonia Icecap and made for utterly gorgeous scenery. I finished the last difficult pitch at 20:05, just as it was getting dark,” he wrote.

Some of the hard, tenuous gray ice still lurked above, and Haley charged up it, though the thought of downclimbing it made him reluctant. Still, he reached the top of Fitz Roy at 9:23 pm.

“[I] could see the lights of El Chaltén 3,000m below. I wondered if anyone down in town was outside taking in some fresh air, and might see my headlamp,” Haley wrote.

He didn’t linger at the “very, very far away” outpost for long.

“I felt extremely anxious about the descent, and started down just a couple minutes after arriving on the summit,” he wrote.

Satisfaction from within

A long but incident-less rappel followed. Haley finally reached his tent at Fitz Roy’s base around 5 am, “extremely wasted physically, mentally, and psychologically.”

He concluded his long blog report just two days later, on September 22. In it, he acknowledged that he still felt the effects of his long exposure on the “Supercanaleta” — and stated that he’s elementally satisfied with his own effort.

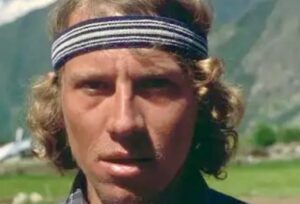

Haley during the first solo ascent of the “Infinite Spur,” Mount Foraker, Alaska, 2016. Photo: Haley via Wiki Commons

“I still feel pretty physically tired from the climb, still somewhat sleep deprived, and certainly still in a daze from the experience. There is no one pitch on the ‘Supercanaleta’ that is extremely difficult or dangerous, but the length of the route, having to be in a hyper-focused state non-stop for 21.5 hours, and doing it all in the cold and solitude of winter made it a very intense experience.

“I know from the intensity of my experience that it was pretty darn badass, and I don’t need external affirmation to confirm that to me,” he wrote.

He concluded by thanking the individuals who supported him on the mission. Most importantly, he said, “for encouraging me to buy the ticket and take the chance.”