We recently published a story about North American birding’s Holy Grail, the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. The last confirmed sighting of this large, loud bird was in 1944. Confined to the swampy forests of America’s Deep South, the bird disappeared because of intense hunting and habitat loss.

Since the last sighting, it has become perhaps the most iconic “lost” species in the United States. Professionals and amateurs alike have searched for it. Like Bigfoot, there have been sightings but no real evidence.

Recently, the bird has been back in the news. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared it extinct in 2021, only for a team of birders to claim that they had rediscovered the species: “Our findings, and the inferences drawn from them, suggest an increasingly hopeful future for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker.”

They are publishing a paper, and several media outlets, including us, picked up the story of their find. The only problem? They almost certainly haven’t found their bird. The three-year study, using microphones, drone cameras, camera traps, and volunteers has only managed to come up with a couple of photos so bad that they are impossible to identify further than, “Yep, that is probably a species of woodpecker.”

Only the photo on the left is from the recent search for the bird. Photo: 90.5 WESA

A five-pixel image

The photos are of such poor quality that it almost looks deliberate. I take a lot of wildlife photos, and many of them are awful: blurred, slightly out of focus, under-exposed or over-exposed. But I’m not sure I’ve ever taken a photo quite as poor as these. They are completely silhouetted and seemingly consist of four or five pixels. I spend a good amount of time identifying birds on INaturalist and can safely say that these photos would fall into the bottom 1% of terrible images uploaded to this global citizen science database.

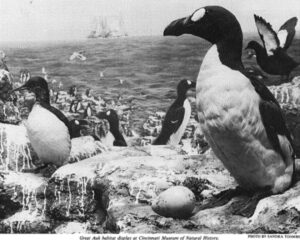

These new photos are usually presented alongside old photos of the species from 1935, which confuses people who might assume that all the images are from this recent study. Funnily enough, the now 87-year-old image is decidedly better quality than the ones taken in 2021.

Discounting the photos, we are left with the researchers’ word that they saw this iconic species. Unfortunately, hope, passion, and drive have a way of warping what people see and remember.

The search for lost species

The conservation field has seen this before. For years, the Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia has rigorously searched for the extinct Tasmanian tiger. More than once, it has claimed success. The group says that its most recent find was not just proof that the species had survived, but that it was breeding.

Neil Waters, the head of the group, was absolutely convinced that he’d cracked it. He even announced the discovery of three tigers, including a juvenile. Unfortunately for Waters, when experts saw the images, they quickly agreed that the footage most likely showed pademelons, a small marsupial not unlike a wallaby.

One of the “Tasmanian tiger” images released by Neil Waters. Photo: Neil Waters

It’s true that lost species sometimes turn up. But this usually happens because the species is small, elusive, and lives somewhere remote, with few people interested in looking for it.

In my neck of the woods, in Vietnam, no one saw the Gray-crowned Crocias, a medium-sized thrush-like bird of the midstory jungle canopy, for 56 years. Then in 1994, someone rediscovered it. During the “missing” years, no one knew where to look for the bird, and barely anyone bothered to try.

To put it into perspective, there are half a million Ebird users (a bird-spotting platform) in North America right now. INaturalist (a citizen science app for all wild flora and fauna) lists 1.7 million bird observations this year in the United States alone. Vietnam has only 1,066 bird observations on INaturalist ever, and half of them are mine. If Vietnam had a fraction of the amateur naturalists that the U.S. does, I have no doubt that the Gray-crowned Crocias would never have been declared extinct in the first place.

A definitely not extinct Gray-crowned Crocia, photographed by the author.

A giant bird that makes a racket

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker is also a much easier creature to see. It’s a large bird that drums on trees and makes loud cries. While new species (primarily reptiles, snakes, and insects) are regularly described here in Vietnam, large charismatic species discoveries are incredibly rare anywhere on the planet.

Likewise, lost species from Vietnam, such as the Indochinese Tiger, are never seen. They don’t come up on camera trap images and are almost certainly locally extinct. (It still hangs on in Thailand and maybe Burma.) If I saw what looked like a large cat moving through the jungle here, the chances are it’s not a tiger. It would be my responsibility to get a good enough photograph if I wanted to announce the rediscovery of the species here.

Like cryptozoologists hunting for Bigfoot or a Yeti, the search for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker is probably self-selecting. You don’t spend three years searching for a species unless you already believe it still exists. I can’t prove they didn’t see an Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, but fortunately, the burden of proof isn’t on me. It’s on the scientists involved, and so far the evidence looks like little more than misplaced enthusiasm. Still, part of me really hopes that they prove me wrong.